Will climatology be the next ‘must-have’ skill in the financial industry?

Will climatology be the next ‘must-have’ skill in the financial industry?

Climate change has been a sensitive political issue for several decades. It is now becoming an economic one as well. Financial institutions are preparing. Advisors should consider doing the same.

Commodities players have always been highly attuned to the weather. Some reasons are obvious. Floods, droughts, and cold snaps can have a significant impact on crop yields and livestock health, which in turn affect price. Others are more obscure. A recent article from the CME Group highlighted a connection between the monsoon season in India and the price of gold. Apparently, 60% of gold purchases in India come from rural areas, and India is the second-largest gold-consuming nation. So, a more benign monsoon season leads to more productive crops and more gold purchases by Indian farmers. Go figure.

If your investment focus is more on equities, bonds, and real estate, however, the weather is generally of such minor concern as to be off your radar screen completely. Take heed. Climate change is coming to an asset class near you.

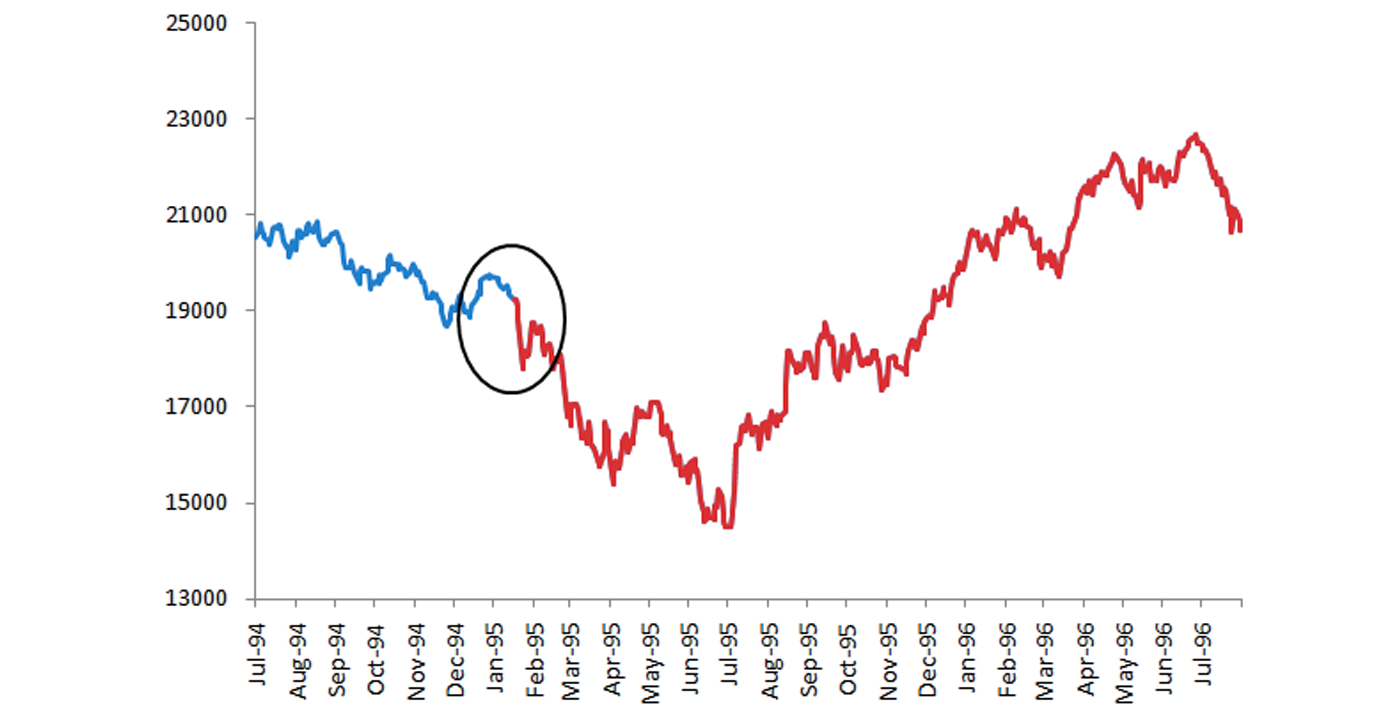

When they are significant enough, intermittent natural events will capture the attention of financial markets. In January 1995, the Great Hanshin-Awaji (Kobe) earthquake in Japan sent the Nikkei average down 25% over the ensuing six months. That’s because it killed more than 6,000 people, completely destroyed more than 100,000 structures, and damaged a half million more.

FIGURE 1: JAPAN’S NIKKEI 225 BEFORE AND AFTER KOBE EARTHQUAKE ON 1/17/95

Source: Bespoke Investment Group

But for the common flood, drought, or wildfire, the market hardly blinks, except when a specific company is directly affected. Two prominent recent examples include Hawaii Electric (HE), the utility company under investigation for its possible role in the recent fire in Lahaina, Maui, and California utility PG&E (PCG), which sought bankruptcy protection in 2019 for its liability in deadly fires.

This, too, is not unexpected, as weather-related disasters are frequent, highly unpredictable, and tend to affect an isolated locality with little overall impact on industry in general or the greater economy.

That perception, however, is changing, along with the reality that underlies it.

The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) reports that billion-dollar-plus weather disasters are on the rise. Since 1980, the average number of billion-dollar disasters in the U.S. was less than nine per year. Since 2018, the average has been 18 per year. The record year was 2020 with 22 such disasters, and we have already broken that record with 23 big disasters through August of this year. That’s more than $57 billion in damage for the year on the back of $165 billion last year.

While these are big numbers each year, the economic impact is diffused through insurance companies, federal disaster relief organizations, charitable organizations, and local governments, with the remainder absorbed by the individuals and businesses affected. This can hurt or even devastate a local economy but tends to be contained regionally. As the number of such events balloons, however, the pain to insurers, governments, and affected individuals is taking on more national significance.

Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA) Administrator Deanne Criswell warned in August of this year that the organization’s disaster fund was running dry and petitioned for more funds. President Biden asked Congress last month for $12 billion, but that hardly seems like it will last very long. In an atmosphere where Congress is intent on reducing federal expenses, future disasters may cast a different economic shadow with more of the damage being absorbed by local victims and more of an impact spreading beyond local borders.

This is where the issue gets complicated by behavioral factors. People have historically viewed the weather as a somewhat fickle phenomenon, characterized by occasional disasters that couldn’t have been foreseen and which amount to “acts of nature.” There was no one to blame, and people rallied together to help one another in times of need.

The notion of global warming and its effect on climate have altered the perception of climate disasters, perhaps irrevocably. Climate change is a relatively new concept raised in the last few decades by environmentalists—initially as an outgrowth of concerns about the ozone layer, and later about the amount of carbon dioxide in the atmosphere. This allows climate activists to blame those responsible for generating the most CO2, as well as federal and local governments for failing to rein in the carbon offenders. Governments also take heat when their aid is deemed insufficient or is poorly managed, despite their extensive disaster relief efforts in the past.

The close relationship between climate change and other environmental concerns made it a lightning rod for the politicization that has permeated the issue on both sides. Some people and organizations claim the whole climate change movement is a hoax created for political reasons. The divisiveness on the issue has reached epic proportions and unfortunately only hinders legitimate efforts to assess and address the problem in any meaningful way. Meanwhile, regardless of who you blame, the planet is getting hotter, climate patterns are changing, and the issue is transitioning from being primarily a scientific concern to an economic one.

Disaster economics

Since today’s society functions in a far more advanced economic environment than any previous one, and since today’s economies evolved under assumptions of stable long-term climate conditions, there are major unanswered questions about how climate changes will impact us economically. The momentum and potentially far-reaching financial effects of climate change, however, suggest that financial advisors will be faced with the risks, opportunities, and radical beliefs about climate change—and other related issues—before too long.

Investment firm Carbon Collective Investment LLC has identified several long-term concerns that it believes have not been sufficiently addressed from a risk-management perspective by the broad investment industry. These include climate risk, biodiversity loss, rising seas, wildfires, significantly higher insurance costs, and the ultimate decline of oil demand/fossil fuel (“decarbonization”).

Thus far, national attention to climate change has been largely focused on evaluating climate science, figuring out how society might take actions to mitigate global warming, and the pursuit of “green energy” initiatives that have included wind and solar power and brought forth new products such as electric vehicles. What is not talked about openly are the risks to existing assets and businesses from property damage, business interruptions, or loss of markets.

While climate risks do not yet appear to have affected the broad public markets, the financial industry is definitely mindful of the potential risks associated with changes in global climate and is seriously looking at them. As an industry that has always put on an optimistic face to the public and preferred to focus on opportunities over risks, however, it is not looking to raise public alarm bells over climate risk. Nonetheless, behind the scenes, it is preparing.

One place in the financial industry where climate is already a front-burner item is the insurance industry, which has always had natural disasters in its sights. Long before the words “climate change” ever became popular, the insurance industry was busy quantifying disasters and responding to increased projected threats by raising rates or withdrawing coverage in selected areas. As far back as 1927, insurance companies stopped underwriting flood insurance in the areas affected by the great Mississippi floods of that time.

For the insurance industry, climate change is a potential harbinger of future liabilities, and the luxury of waiting to see how things turn out is not an option. Primed with climate models and reeling from the economic realities of recent and unprecedented weather-related property disasters, insurers and reinsurers have been busy positioning themselves for what they see happening. In recent times, insurers and reinsurers have become rather aggressive about raising rates and declining coverage.

Just this year, State Farm, Allstate, and AIG stopped taking on new policies in California. Farmers Insurance has announced they will stop writing new policies in Florida. And in Louisiana, 12 insurers have left the market in the past three years. CBS News reports that, according to climate research nonprofit First Street Foundation, about 35.6 million properties “face increasing insurance prices and reduced coverage due to high climate risks.” That’s one-quarter of all U.S. real estate.

In Florida, the insurance debacle is playing out in real time. Residents pay an average of $6,000 annually for home insurance versus a national average of $1,700. For insurers, the politicized version of climate change is irrelevant. If the models say more homes will be destroyed by fires, floods, and other weather-related catastrophes in the future, it doesn’t matter whether the event can be indirectly related to human or industrial activities. More disasters mean more liabilities and higher rates.

Even if climate change had nothing to do with the frequency of disasters at all, new land development has continued to occur in disaster-prone areas and people have moved there. So, insurance companies and reinsurance companies have had little choice but to raise rates if they wish to remain solvent.

The cost of insurance not only acts as a tax to individuals, it ultimately exacts a valuation toll on home values. Until now, lower home values in known disaster areas remain isolated amid a sea of rising prices in real estate overall due to limited supply. But a continued trend of more frequent disasters coupled with even higher insurance rates could potentially lead to a reckoning in the real estate market.

In historically flood-prone areas such as Louisiana or North Carolina, there is now a lot of data history to support higher insurance rates. With something like potential sea-level rise, the story is different. There is no history of sea-level rise to draw upon, so insurance companies must make their best guess from climate models. If they stop writing policies along the coasts, the number of homes involved will quickly escalate into the millions.

The industry most closely affected by rising insurance rates would then become the mortgage industry. In some areas, mortgage lenders might pull out even before insurance companies. Once lenders determine that your home has an existential risk inside of the 30-year horizon on your mortgage, they may decline you, even if you can still get insurance.

More broadly, equity markets should not be expected to remain immune to climate risk either. Many in the financial industry can still vividly recall what a wholesale drop in real estate prices did to the equity markets in 2008. So, while public companies are at risk of property damage to their own assets, the equity market as a whole would also expectedly fall as a side effect of a widespread decline in residential real estate prices.

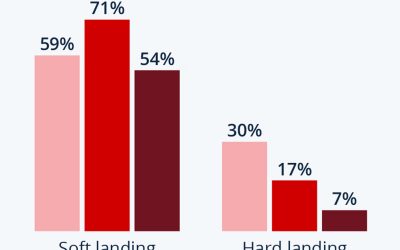

Figure 2, from a recent KPMG study among corporate executives, suggests that climate risks have not gone unnoticed within corporate America, either.

FIGURE 2: CORPORATE AMERICA VIEWS CLIMATE RISK AS A CRITICAL ISSUE

Source: Eversheds Sutherland and KPMG, “Climate change and corporate value,” 2020.

As a result, attention to the potential risks in equities is rising also. In January 2022, information and analytics behemoth S&P Global quietly acquired The Climate Service, a climate analytics company, and began assessing the climate risks of large global companies. In September 2022, S&P Global released its first conclusions from its newly created climate risk database, stating that “92% of the world’s largest companies will have at least one asset at high exposure to a climate change physical hazard by the 2050s” and that “over a third of the world’s largest companies have at least one asset where the physical risks of climate change are equivalent to 20% or more of that asset’s value by the 2050s.”

Additionally, since climate issues are essentially environmental issues, they are often confused with ESG (environmental, social, and governance) concerns, which are having their own moment in the spotlight. There are big differences, however. ESG measures were primarily developed to rate companies on their adherence to social and ethical issues related to corporate governance or the environment. As such, they might include measures of a company’s pollution profile or carbon footprint. But while such measures may indicate whether a company is potentially contributing to global warming, they do not indicate whether the company has a risk from global warming. As a result, climate-related risks to physical assets or business continuation are not generally included in ESG ratings.

The challenge of climate change

Dealing with changing economic conditions and client circumstances is, of course, what advisors do. So, in some respects, navigating the financial impact of climate change will be an extension of an advisor’s current business. But it does reemphasize the continued importance of having a strong risk-management orientation in place for clients’ investment portfolios.

In other regards, however, the nature and scope of climate change may present some radically new challenges that haven’t even yet been fully defined. Some of these include the following:

- The potential for significant—and perhaps rapidly changing—financial risk to existing client assets, including homes and properties.

- The challenge of dealing with a highly complex planetwide phenomenon that already has a strong degree of variability associated with it.

- The need to consider very long-term horizons.

- The need to deal with potential black swan events (those with a low probability of occurring but significant potential consequences).

- Strong emotional ties to the places we live and the risk of social upheaval associated with being forced to move.

- Dealing not only with financial impact but also legal and political impact at the same time.

- And last, but not least, navigating a controversial subject with strong voices on both sides of the climate issue.

I emphasize the risk-management side of climate economics because it is not as widely discussed in the public arena, but none of this should suggest that opportunities won’t exist as well. A wide array of climate-related innovation is genuinely underway, both for mitigation as well as adaptation. As in other areas of corporate innovation, many climate change success stories are likely hiding in the wings. As expected, there is also already a bevy of thematic ETFs in green energy, solar, infrastructure, and carbon transition available as well.

In addition, even property damage—unfortunate as it is—can lead to growth opportunities, as both people and businesses relocate to new areas expected to have more favorable weather conditions.

Thus, for advisors, the climate revolution will bring opportunities to differentiate and take advantage of new growth, as well as to help protect client assets from unanticipated risks. The key to future success as an advisor might involve some additional education in, of all things, climatology.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and the sources cited and do not necessarily represent the views of Proactive Advisor Magazine. This material is presented for educational purposes only.

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.

RECENT POSTS