Are advisors missing the point about behavioral finance?

Are advisors missing the point about behavioral finance?

Behavioral finance is now part of the investing lexicon, but how much are advisors really using the discipline? And if so, are they using it in ways that are best able to impact their practices?

One of the many things we have learned from behavioral science is that people tend to think rather highly of themselves—a trait that falls under the broad category of overconfidence bias.

A classic illustration of this is the driving skill poll conducted by a behavioral psychologist. Subjects were asked to rate their driving skill the last time they drove their cars. Not surprisingly, they gave themselves glowing ratings, as people are prone to do. What made these results stand out was that the poll was conducted in a hospital among subjects that had all suffered injuries from recent auto accidents.

This demonstrates, among other things, that people have a strong behavioral tendency to say things that allow them to feel good about themselves and to provide responses they perceive will make others feel good about them—even if exaggerated or in some cases flat-out untrue.

I bring this up because I commonly see polls of financial advisors that ask whether they use behavioral finance in their practices. Most advisors today will say yes to this inquiry, though I expect that number would drop considerably if the subjects were asked to cite specifics. What’s more, I suspect very few at all could cite a definitive measure of improvement in their practices that could be directly attributed to behavioral finance.

That’s not to say behavioral finance isn’t having a positive impact for advisors or that they are all paying lip service to researchers. It does, however, raise the question about how broadly and effectively advisors are using behavioral finance and whether they are applying it where it might produce the greatest potential impact.

Based on what I hear from my behavioral finance students, I have reason to believe that many are not.

One reason why the impact of behavioral finance on advisory practices is not more readily apparent is that many advisors may be looking in the wrong place for that improvement.

Behavioral science teaches us how people think, how they may make judgments and decisions, and how they perceive their world. In turn, this can provide valuable insights as to their leanings, biases, preferences, predispositions, and behavior. The primary ways this knowledge can be used are as follows:

- Improve one’s own behavior with regard to investing (self-improvement).

- Change the behavior of others (coaching or financial therapy).

- Use that knowledge to influence the behavior of others (marketing, client relations).

- Use that knowledge to understand better how markets move (analysis/trading).

So, where should financial advisors lie within this spectrum? I would submit that “using that knowledge to influence others” is the activity most closely associated with an advisor’s role. But that is not how all advisors see it.

In the more than 10 years that I’ve been teaching behavioral finance to CFP candidates at UC Berkeley, I’ve been asking students at the beginning of the first class to tell me where they expect behavioral finance to provide them with the greatest impact. The choices I give them are as follows:

- Your personal investing.

- Client investing.

- Client acquisition.

- Client relationship management.

- Market understanding.

- Other (please specify).

The student response is predominantly “a,” telling me that they see behavioral finance as a means of improving their own performance as investors more than anything else. This suggests that many of them may view advisor success as primarily a function of investment performance—a perspective that many advisors are trying hard to change. (Of course, some students may interpret “a” as building personal investment skills that are then transferable to their efforts on behalf of clients.)

The “a” response would be entirely appropriate for professionals who manage money rather than clients, such as an investment manager, a professional trader, or a fund manager. Indeed, many traders and managers now employ behavioral tools or coaches to specifically help them evaluate their performance from a behavioral perspective and make changes accordingly.

For advisors, however, the more relevant answer should be “d,” and I offer several reasons why.

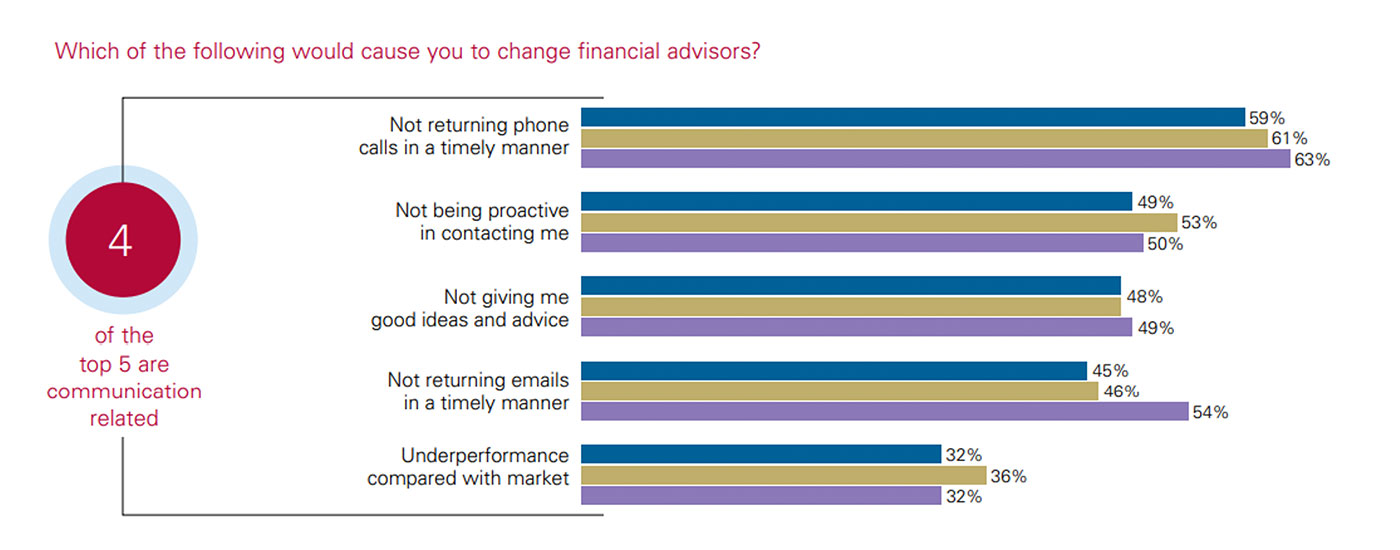

First, client-management issues consistently outrank portfolio performance in studies about why clients leave their advisors. The studies have shown throughout the years that while performance cannot be ignored, client communication and the ability to relate well to the client’s needs are the reasons given most often for why clients change advisors.

A research study from Vanguard (conducted by Spectrem Group) indicated that “four of the top five factors that would cause an affluent investor to leave an advisor are communication-related.”

Source: Spectrem Group, Vanguard Investments Canada Inc. Please see entire study here.

A classic example of this client behavior can be found in the experience of Dr. Michael Burry, the real-life hedge fund manager featured in the book “The Big Short” by Michael Lewis. Even in a hedge fund role, where performance should be the primary determinant of client satisfaction, Dr. Burry fell victim to many client defections after alienating his clients, despite what would be the ultimate success of his strategy. That strategy generated enormous profits from prescient short positions on credit default swaps during the subprime mortgage crisis.

Secondly, using behavioral finance to improve one’s own investment behavior is illusive. The nature of behavioral biases is that they are firmly entrenched in our psyche (psychologists use the term “hardwired”), and there are severe limits to how much any of us can effectively change our own behavior. It’s not impossible, but it will almost certainly require outside help, which is why professional traders and fund managers who are serious about behavioral improvement may seek outside help from behavioral coaches. Even then, there is no guarantee that changing your behavior will automatically translate into consistently better investment performance.

Daniel Kahneman, who was awarded the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences, anticipated this question in the conclusion of his book “Thinking, Fast and Slow.”

Kahneman asks, “What can be done about biases? How can we improve judgments and decisions? The short answer is that little can be achieved without a considerable investment of effort. It’s not a case of: ‘Read this book and then you’ll think differently.’ I’ve written this book, and I don’t think differently.”

Kahneman goes on to admit that one can expect more progress in recognizing the errors of others than their own, supporting the notion that behavioral coaching is generally necessary for changing one’s behavior.

A third reason why behavioral science can have greater impact on client relationships is in the leverage. Even if you are able to change your own behavior and realize materially better investment performance, how will you translate that into success for every one of your clients unless you were actively managing all of their money? On the other hand, you can achieve leverage across your entire client base by using behavioral principles applied to the way you handle your clients.

While we may understand behavior much better now than before, our ability to change it, particularly in ourselves, can be a very difficult exercise. On the other hand, advisors may be able to effect considerable impact on their practice through any of numerous actions aimed toward more effective client acquisition, better client management, and reduced turnover.

These actions will be directed more toward influencing clients than changing their behavior. They might involve steering (or nudging) a client toward a given objective, presenting things in a way to achieve better compliance from clients, or using choice architecture to guide their actions in the same way big companies use it to nudge us into buying their products. As a result, client relationships should emerge stronger through greater trust, respect, knowledge, and understanding between client and advisor.

Based on what we know about how clients think and behave, here are some of the actions you might want to build into your advisory practice from a behavioral perspective:

Client acquisition. Audit your approach, methodology, and positioning. Prospecting generally needs to be refreshed to remain current and meaningful. You should not expect that a one-size-fits-all acquisition plan is attracting all the right people all the time. Are you too narrowly focused? Are you hitting the right buttons for current times? Is your message getting to the right audience and is it resonating? Do you know why the clients you have already acquired have chosen you?

Client onboarding. Behavioral studies tell us first impressions are lasting ones, and the onboarding experience is a client’s first experience with you on an operating basis. It should be viewed as every bit a client-satisfaction exercise as any other interaction, perhaps even more important since it is the first. Make it as seamless as possible and check in with the client throughout the process. Also, don’t leave the process entirely to an administrator or less experienced associate. Make sure you establish in the client’s mind that they are important enough to command your attention as their advisor at all stages of the relationship.

Client assessment. The single greatest impact of behavioral concepts is likely to be connected with your client discovery sessions and assessments. It is difficult to overemphasize their importance if for no other reason than it determines the basis on which the advisor-client relationship will proceed. That means mistakes, omissions, or misinterpretations during this process will impact your interactions for months or years to come, magnifying their impact.

Client assessment is where you should apply as much of your behavioral skills and knowledge as possible. It is where you truly get to understand your client—their goals, sensitivities, concerns, risk tolerance, and relationship preferences. The better you are at determining these things early in the relationship (and documenting them!), the better your chances for relationship success. Your client assessment should encompass multiple meetings, deliberate topics, and frank conversations. The more comprehensive this process, the less inclined your clients will be to want to go through it again somewhere else.

Client retention. Retention is all about finding out there’s a problem before the client decides to leave. To do that, you need to communicate often and probe your client for concerns or discomforts. They may not always be forthright with you, so you have to be alert to cues. Some advisors hire third-party counselors to touch base with clients now and then to see if there are issues they may not have brought to the advisor.

An often-overlooked aspect of retention is the preservation of a client relationship following the death of the primary client. This means cultivating relationships with other members of the family, particularly spouses and heirs, during the relationship so that continuity can be maintained when the estate changes hands.

Client updates. Updates at regular intervals or when circumstances change are on every advisor’s to-do list, but are they being done from a behavioral perspective or simply a financial one? People change their behavioral profiles as they age or when major life circumstances change, such as occupation, marriage, or health. It’s not enough to just update assets and goals. Client updates should include in-depth conversations about lifestyle changes, risk tolerance, concerns, family issues, or evolution in their investment outlooks.

Client engagement. Advisors should recognize that every opportunity to engage with a client is a chance to deepen the relationship and to learn more about the client. Whether a social event, a learning event, or even a community-service event, client engagement provides an opportunity to become better informed about the client as well as to tap changing moods, desires, or life circumstances. A client would likely contact their advisor following a major job change, for example, but client engagements may provide the opportunity to find out long ahead of that event that the client was even looking for a change.

* * *

Many bright-eyed financial-advisor aspirants like my students cling to the illusion that through study and hard work, they can become some kind of super advisor with a secret sauce for making clients wealthy beyond their expectations.

They are clearly misguided about the ease of generating wealth, but they aren’t necessarily wrong about a secret sauce. The deep insights that have emerged through behavioral finance hold great potential for developing a secret sauce that makes for successful advisory practices by focusing on client satisfaction rather than primarily on portfolio performance.

The trend in today’s advisory environment toward the use of third-party investment management only serves to reinforce this recipe for success. Advisors and clients, more than ever, are acting as a team to objectively evaluate investment performance without the sensitivities of this being a direct personal commentary on the advisor’s investment skill set. (That said, evaluating, selecting, monitoring, and consulting with third-party managers requires its own set of skills.)

It does not take very long as a practicing advisor to recognize the value of client relationships and to discover that client satisfaction is something you may have learned how to maximize in your behavioral class, rather than in your portfolio management class.

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.