The Federal Reserve cut interest rates last week for the first time since 2007.

With strong memories, or nightmares, of the market collapse after the last rate cut, one could draw the wrong conclusion of how extremely bullish this rate cut is.

STIR Research analyzed 16 prior cases over the past 65 years of what happened to the market after a first rate cut following a period of stable or rising rates.

This period covered a full landscape of different conditions: financial expansion and collapse, periods of war and peace, political drama (Nixon resignation to Clinton impeachment), the rampant inflation of the 1970s, double-digit interest rates to negative yields, market meltdowns, and the longest bull run in U.S. history.

Secular markets often last one or two decades. A secular bull market can have corrections and bear market periods within it, but they will not reverse the trend of upward asset values. Similarly, a secular bear market can have periodic bullish periods, but the longer-term trend is for flat-to-lower asset values.

Sorting through the data, one trend stood out. Double-digit gains follow the first rate cut when the secular trend is bullish.

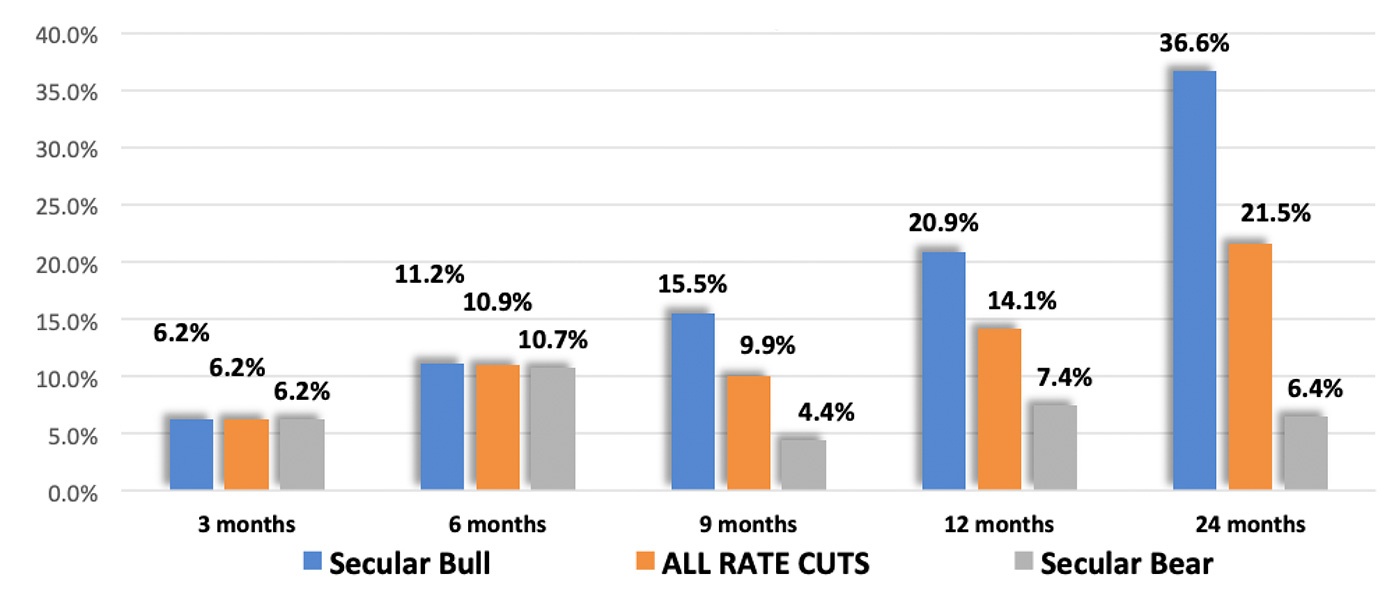

For the first three to six months, it doesn’t make any difference if the secular trend is bullish or bearish. Gains of 6% and 11% are the norms. But looking further out, the differences become dramatic (see Figure 1).

Source: STIR Research

At nine and 12 months following the first rate cut, gains in secular bull markets are three times larger than gains in secular bears. Looking out two years, the average gain is six times greater in secular bull markets. Putting some numbers to the return statistics, if the S&P 500 were to experience an average gain in a secular bull market, it would be approaching 3,370 in January 2020 (six months out), over 3,600 by next summer (12 months), and trading near 4,100 in two years!

Would a recession change the outlook? No, or not in the negative way you would think. In the 16 cases, nine were followed by a recession the following year. In a secular bull market, the average returns after 12 and 24 months, with no recession, were 16.2% and 36.5%, respectively. When recessions popped up a year later, the 12- and 24-month returns averaged 28.7% and 36.9%, respectively.

But the market is already at record highs. Does that change the outlook? No. It is hard to believe, but returns actually improve in those scenarios. There have been multiple times when the Fed has cut rates when the market has been at or near highs: 1954, 1967, 1970, 1984, 1989, 1995, and 2007. Looking at the data through secular bull “glasses,” which eliminates 2007, the average 12- and 24-month gains were 20.1% and 40.6%, respectively.

Forget “the average.” Tell me the best and the worst. Unsurprisingly, the best case was in a secular bull, 1954, when the market gained 40.5% in one year and 70.3% after two years. The worst case was in a secular bear market, 2007, when the 12-month loss was 20.6% and 29.7% at the end of the second year.

What if the rate cut is just “one and done,” or simply a midcycle adjustment within a longer-term trend of rising rates? Looking at history for guidance, in the 20-year secular bull market from 1949 through 1968, the S&P 500 rose 700%. During that time, rates rose from less than 1.0% to over 5.5%. The Fed also entered into four “midcycle adjustments” during that period, where rates were cut within a longer-term rising rate cycle. In those cases, the average gain after the first rate cut 12 months later was 23.2% and 30.7% two years later.

Buy equities! The market is just seven months into a new cyclical bull market run following the Q4 2018 cyclical bear market. There is a lot of time and upside left in this new cyclical bull run. Profit from it.

Marshall Schield is the chief strategist for STIR Research LLC, a publisher of active allocation indexes and asset class/sector research for financial advisors and institutional investors. Mr. Schield has been an active strategist for four decades and his accomplishments have achieved national recognition from a variety of sources, including Barron's and Lipper Analytical Services. stirresearch.com

Marshall Schield is the chief strategist for STIR Research LLC, a publisher of active allocation indexes and asset class/sector research for financial advisors and institutional investors. Mr. Schield has been an active strategist for four decades and his accomplishments have achieved national recognition from a variety of sources, including Barron's and Lipper Analytical Services. stirresearch.com