An interesting footnote to ‘Sell in May and go away’

An interesting footnote to ‘Sell in May and go away’

Editor’s note: This article was originally published by Larry McMillan in The Option Strategist Newsletter on May 23, 2014. The insights are still valuable in this year’s investment environment.

Not wanting to merely accept someone else’s work without checking, I coded up a study of my own. If $SPX trades at a new all-time high in May:

- What did the market do from the end of May until the end of the year?

- How did $SPX perform in the “Sell in May …” period (i.e., from the end of April through the end of October)?

$SPX was created in its present form in 1957. Although it was backdated before that, most data sets have $SPX historic prices only back to the beginning of 1950. Standard & Poor’s created its first stock index in 1923, but I used only the post-1949 data for this study.

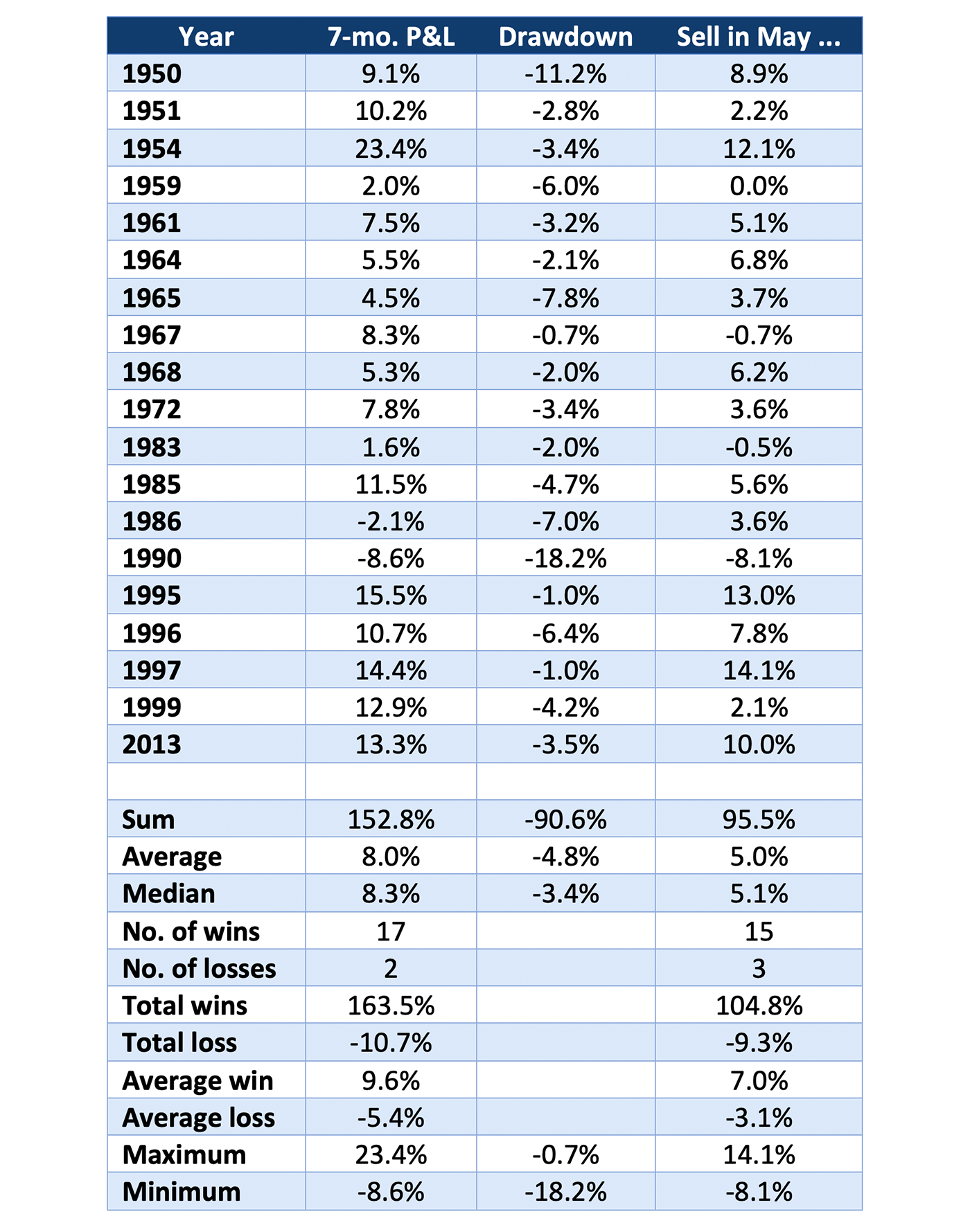

It turns out that $SPX has reached a new all-time intraday high 20 times during the month of May, including this year ($SPX made a new all-time closing and intraday highs on May 13, 2014). In 17 of the previous 19 years (we don’t know the outcome yet this year), the market rose in the seven months from June through December. In other words, this is a new seasonal indicator of sorts: When $SPX makes a new all-time intraday high in May, then buy “the market” at the close of the last day of May and hold through the last trading day of the year.

The average gain for all 19 years was 8.0% over the seven months. In the 17 winning years, the average gain was 9.6%.

The best year was 1954 (which even I am not old enough to remember), when the seven-month period produced a gain of 23.4%. The years 1995, 1996, 1997, and 1999 produced new highs in May and double-digit gains for the seven-month period.

The only two losing years were 1990 and 1986. When Iraq attacked Kuwait in early fall of 1990, the market rallied back late in the year. However, the seven-month period still ended with a loss of 8.6%. In 1986, the seven-month period produced a modest loss of 2.1%.

Drawdowns

Merely knowing that one could buy and hold for seven months and make money doesn’t tell the entire story. For example, what kind of drawdowns were there? It turns out, they were modest. The average drawdown for all 19 years was 4.8%, including the 18.4% drawdown in 1990, which was the worst one. The median drawdown was 3.4%, reflecting the outlier that 1990 is.

In winning years, the average drawdown was 3.8%, and the median drawdown was 3.4% (the same as when all years are considered).

The smallest drawdown for the seven-month period was 0.7% in 1967.

Sell in May and go away

Even with these seemingly positive statistics, one might wonder how the traditional “Sell in May and go away” seasonal trade fared in these years compared with how it normally performs.

The “Sell in May and go away” seasonal trade was established by Yale Hirsch many years ago. The complete statistical analysis of this seasonality can be found in the Stock Trader’s Almanac each year. Jeff Hirsch, Yale’s son and keeper of the flame, has refined the system in recent years to generate better entry and exit points. However, the original system was to sell at the close of trading on the last day of April and buy back in on the last trading day of October.

Using that definition, for the 19 years in which a new all-time intraday high was made in May, the average year saw a gain of 5.0% from May through October. There were 15 winning years and three losing years (one year was flat). The best performance was a gain of 14.1% in 1997, and the worst was a loss of 8.1% in 1990.

Table 1 provides a year-by-year summary, followed by totals, for the 19 years in which May has seen a new all-time intraday high.

TABLE 1: YEAR-BY-YEAR RESULTS WHEN ALL-TIME HIGH OCCURS IN MAY

According to the 2014 edition of the Stock Trader’s Almanac, the Dow Jones Industrials averaged a mere 0.3% gain from May 1 through Oct. 31 during the period from 1950 to 2012. If you had invested $10,000 in 1950 and persisted in being long only in those six months each year, you would have wound up with a loss of $1,105 by Oct. 31, 2012. There were 37 winning years and 26 losing years. The biggest gain was 19.2% in 1958, and the biggest loss was 27.3% in 2008 (1973 also produced a loss of more than 20%).

One can see that the results for the May–October period in the 19 years in which $SPX made a new all-time high in May were far superior to the totality of all years (an average 5.0% gain versus an average 0.3% gain, respectively).

This might be useful, for example, if you exited your positions (or were even short the market) because of the “Sell in May and go away” philosophy. You would have exited your longs (and maybe gone short) at the close of trading on April 30. However, if during the next month $SPX traded at a new all-time high, you could use this new information to reestablish positions at the end of May, figuring that the remainder of the year would produce good results, on average.

All of this is interesting information that augurs for higher prices ahead this year.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and the sources cited and do not necessarily represent the views of Proactive Advisor Magazine. This material is presented for educational purposes only.

This is an edited version of an article that was first published at optionstrategist.com on May 23, 2014, and republished on May 21, 2024.

Professional trader Lawrence G. McMillan is perhaps best known as the author of “Options as a Strategic Investment,” the best-selling work on stock and index options strategies, which has sold over 350,000 copies. An active trader of his own account, he also manages option-oriented accounts for clients. As president of McMillan Analysis Corporation, he edits and does research for the firm’s newsletter publications. optionstrategist.com

Professional trader Lawrence G. McMillan is perhaps best known as the author of “Options as a Strategic Investment,” the best-selling work on stock and index options strategies, which has sold over 350,000 copies. An active trader of his own account, he also manages option-oriented accounts for clients. As president of McMillan Analysis Corporation, he edits and does research for the firm’s newsletter publications. optionstrategist.com

RECENT POSTS