The market has already rallied sharply off the lows from earlier this year, but history shows that more gains—maybe another 20% or 30% or more—may be on the horizon.

It became apparent in early June after the release of the April GDP numbers that the U.S. economy was in a recession, thus ending a record 128-month expansion. This was according to the National Bureau of Economic Research (NBER), the official scorekeeper of recessions.

The standard definition of a recession is two consecutive quarters of economic decline. Though the economy peaked in February, NBER believed the steep drop in GDP in March and April was enough to make the recession call, noting that the unprecedented magnitude of the decline in employment and production had reached across the entire economy.

By the end of July, the economy had suffered two quarterly declines in GDP. The recession will officially end when the bleeding stops, even if it takes years for the economy to make a full recovery. May and June saw small monthly gains in GDP from the April low; however, the third quarter may see some early backsliding as upticks in COVID-19 cases caused some states to either pause or reverse their plans to reopen.

So is the recession over, or is the worst yet to come? We don’t know yet, but when the end does come, investors should be prepared for market gains.

The market is a leading indicator, typically dropping before the start of a recession and rallying before the start of the recovery. That has been the case this year. However, investors worry that the big gains since the March lows have taken the market too far, too fast.

In the prior 11 recessions, the S&P 500 rallied on average 25.5% before the recession officially ended. This is very similar to our current situation. If NBER makes the call that the recession ended in April (or May or even June), the S&P would have gained roughly 30% from the March low. This is pretty close to average conditions in the past 11 recessions.

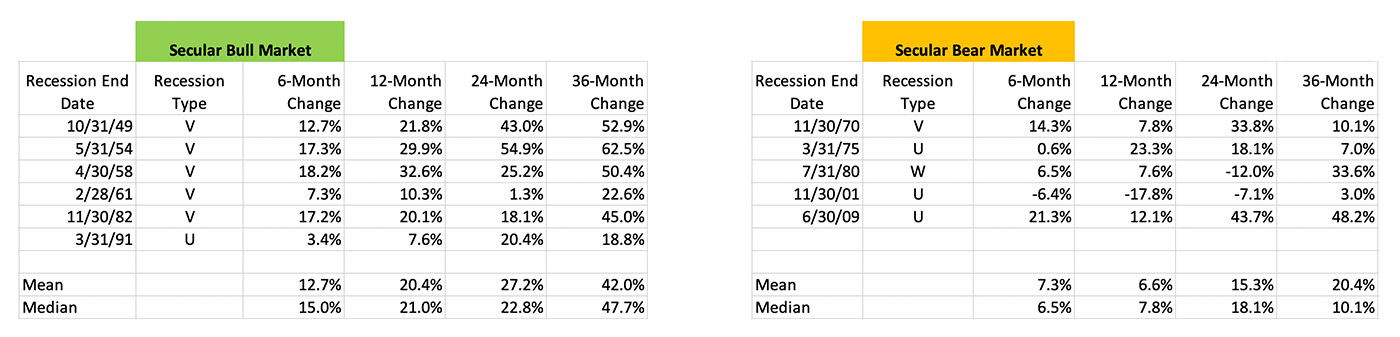

The good news is that even bigger market gains have typically followed the end of recessions.

Sources: S&P Dow Jones Indices; recession dates determined by the National Bureau of Economic Research

Currently, strategists and economists are arguing over the shape of the expected recovery. Will it be a sharp V, rising as fast as it fell? Will it be a U, a period of bottoming before a sharp recovery? Or will it be a W, characterized by a strong and fast comeback followed by another economic dip? Some argue for a “Nike swoosh recovery,” characterized by a longer bottoming process and a steady and gradual rebound.

The most recent recession was from December 2007 to June 2009. The market peaked in early October 2007, two months before the start of the recession, and bottomed on March 9, 2009. The S&P 500 had rallied by 36% before the official end of the recession on June 30, 2009. It turned out to be a U-shaped recovery. If in June 2009 you had thought you had already missed out or that “the market went too far, too fast,” you would have missed out. The S&P rallied another 44% over the next 24 months!

Another thing to consider: In secular bull markets (such as the one I believe we are still in) after the official end of a recession, the market has moved higher, on average, 39 months before the start of another 20% correction. The shortest rally was the 10 months following the end of the 1961 recession, and the longest was the 88-month rally after the 1991 recession.