What happened to the case for active risk management?

What happened to the case for active risk management?

If formal risk-management strategies provided a demonstrable advantage versus passive strategies during the COVID-related decline of 2020, why is that story not coming out? And if there was no advantage, what does that mean for active risk management?

Amid the Q1 2020 swoon in stock prices and the overwhelmingly negative economic news, there should have been a silver lining for active risk-managed strategies, even if only in the form of a more modest decline for such portfolios compared to their respective benchmarks.

Other than anecdotal evidence, some of which revealed strong performance for risk-managed strategies, available data cannot really answer that question.

A recent analysis by Morningstar looked at the performance of all active funds during the initial sell-off resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic between Feb. 20 and March 12, 2020. Fully 52% of actively managed funds produced excess returns during this steep decline, with an average margin of outperformance of 2.16% for those active U.S. stock funds that beat their index. But the reported average excess return among all active U.S. stock funds during this period (before fees) was a paltry 0.16%. Meanwhile, the benchmark S&P 500 Index fell 27% during this period.

At face value, there’s essentially no silver in that lining at all.

However, Morningstar does not separately identify a subset of active investment managers who engage in formal risk-management strategies, meaning the data is so diluted with managers not using risk management that it provides us with almost nothing useful about the performance of risk managers.

Moreover, the classification of active managers itself is muddied by a wide assortment of styles and techniques that are categorized as “active” in an arbitrarily binary manner that identifies passive managers and then more or less classifies everything else as active. This process results in a generalized characterization of active management that can be highly misleading when drawing performance conclusions.

A search on Morningstar’s website shows its parameters for every fund category it defines but fails to turn up a definition for how it classifies a fund as being actively managed. A strategic beta or multifactor fund, for example, could be listed among active funds, but few would consider factor tilts a true form of risk management.

In fact, no matter how an investment manager selects stocks, if the strategy is to remain fully invested in equities through all cycles and circumstances, then it may well be actively managed but should hardly be considered risk managed.

Older research echoes this performance paradox. Research Affiliates concluded that 2008 “was the worst calendar year of performance for a mainstream portfolio of active managers going back to 1990,” calculating that an actively managed 60/40 portfolio underperformed the passive equivalent by 3.4 percentage points in 2008, before fees. Unsurprisingly, a 2009 paper by then professors Sun, Wang, and Zheng of UC Irvine studied nearly three decades between 1980 and 2008, concluding that active funds as a group “did not significantly outperform the passive index funds” during that entire period. Again, there was no distinction for active managers that were managing risk.

Such studies provide gratuitous support for the marketing efforts of passive funds but unfortunately mask the success of active managers whose performance numbers are buried along with others that do not embrace proactive risk-management strategies and may not even deserve to be labeled “active” to begin with.

So, even though we know intuitively and anecdotally that active risk management should outperform during market swoons, we don’t have the luxury of valid published data to support that contention, and we won’t until the industry takes a deeper approach to defining active risk management and tracking performance accordingly. Nonetheless, the recent pandemic-generated market slide provides an excellent time for self-reflection on the role that risk management plays among active managers and whether that role, or its associated narrative, should be re-examined.

An effective narrative around either active management or active risk management requires valid definitions with which to classify funds and managers so that evidence of category performance will be both measurable and valid. These definitions should also map to the intuitive perceptions of advisors and investors so they can make proper assessments about the merits of both active managers and risk managers.

Neither of these is effectively happening today.

That’s unfortunate.

The case for risk-managed strategies revolves around intuitive logic that has enjoyed broad appeal and is a widely sought-after quality in investing—the mitigation of downside risk.

A Cerulli Associates report issued in 2020, “U.S. High-Net-Worth and Ultra-Net-Worth Markets 2019,” put some dimension to this, saying in the press release for the report, “Asset and wealth managers currently servicing or seeking to grow their market share in the high-net-worth (HNW) market must be prepared to address investor needs with specific and targeted strategies that can protect client capital in increasingly volatile markets. … More than four-fifths (83%) of HNW practices say wealth preservation is the most important investment objective when working with their clients, according to Cerulli’s research.”

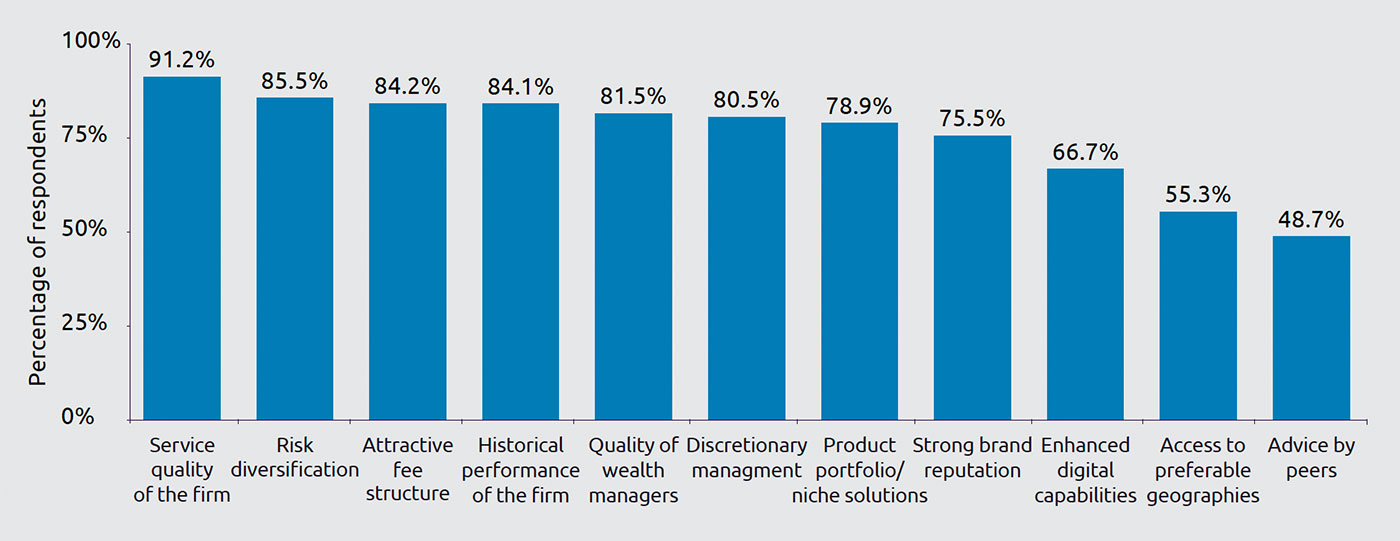

Capgemini’s “World Wealth Report 2019” reported that among HNW investors, “risk diversification” was the second most highly rated attribute in the selection of a wealth-management firm.

Source: Capgemini Financial Services Analysis, 2019; Global HNW Insights Survey, 2019

There has always been an audience for risk-controlled investments, and the demand for fixed-income allocations, banking products, insurance, and hedge funds attests to the level of investor interest in lowering the risk of their portfolios. In other words, peace of mind has value.

And prospect theory tells us that, due to loss aversion, it has a lot more value than we think and people are happily willing to relinquish some upside potential to get it. From a behavioral perspective, one could argue that for many people, it is much more important to know whether their manager engages in risk control than it is to know whether they focus on large- or mid-cap stocks.

As such, active managers who are practicing a strategy designed to materially reduce risk should be able to leverage that as a core aspect of their narrative, even when long-term performance is below the benchmark.

To do that, though, they will need to overcome some of the biases that investors may still harbor from historic notions of what active management is really all about. In the 1970s and 1980s, brokerage firms were propagating a mindset that the road to riches was to use their research ideas and trade frequently. It’s entirely possible that many of today’s baby-boomer clients still equate active management with taking more risk rather than less. For managers who specifically seek to reduce downside risk, that old impression of active management is in direct conflict with reality.

We need to define exactly what constitutes formal risk management so that we can differentiate managers who might just move into more defensive stocks but remain long from managers who are using techniques that actually hedge the downside in one way or another, such as those who employ tactical asset allocation, derivatives or volatility hedging, inverse funds, or short positions.

Any strategy that holds long equities with no other assets, derivatives, or short positions is not engaged in risk management and will essentially be dragged down in close approximation to its appropriate index during a market decline, give or take the small alpha that may exist from the manager’s stock selection. In other words, you may have an account that is actively managed but not risk managed. In my view as a finance professor, stock selection by itself should not be considered a formal risk-management strategy.

The absence of a properly defined category for risk management dilutes the narrative by implying there is no distinction between “active management” and “risk management,” and that is a disservice to the investing audience as well as to investment managers who use formal risk-management strategies.

Once upon a time, clients may have naively believed that a manager could be clairvoyant enough to see the dark clouds on the horizon and steer their portfolios out of harm’s way. But in the modern era of investment management, it’s all about the mathematics of portfolio theory, and managers may need to fold more of that math into their narrative.

Knowing the historic correlations between stocks, investment managers can design portfolios that all but eliminate idiosyncratic risk in managed portfolios. However, systematic risk remains. A 60/40 mix with bonds may dampen that risk and reduce volatility, but it doesn’t eliminate the downside by any stretch.

The same may be true for broader asset-allocation strategies as well. In fact, the degree of downside protection can vary extensively by the risk-management technique employed, its strategic timing, and the criteria for initiating it.

Its results will then vary with the nature of the sell-off and the period in which the decline unfolds. An inverse fund, for example, is not a valid long-term hold but a short-term tool designed to be used at a manager’s discretion when conditions warrant. On the other hand, a 140/40 long-short strategy can be used as a long-term hold. The narrative from investment managers should reflect these differences in their approach to managing risk.

The narrative on risk management can also be fine-tuned to reflect the types of declines in which different techniques are expected to outperform. The blunt reality for active managers may be that the techniques used during bull market corrections or cyclical bear markets may not be as effective during extreme black-swan sell-offs. It may be that some risk-management techniques work well in environments where the equity markets weaken in response to cyclical economic factors but do not do so well in declines that result from unforeseen and sporadic panic and uncertainty.

By their very nature, time and circumstance can be anathema to risk-management strategies and narratives.

Availability bias (overweighting recent events in our perceptions) would undoubtedly have caused investors to be complacent in 2018 or 2019 following one of the longest bull markets in history. Now, with the initial COVID-19 pandemic decline behind us, that perception would likely be quite different. Since risk is inextricably related to time, it is similarly related to risk management.

Risk managers who incorporate a hedge of some sort into their permanent ongoing strategy should essentially put forth a different narrative than those who only deploy a hedge when circumstances dictate.

With an “always on” hedge, it will be characteristic of performance to underperform during advancing markets in order to outperform during the declines. Any long-term measurement of performance under this scenario will be wholly dependent on the period measured and the number and degree of advances and declines during that period. This can prove challenging for all parties involved and will result in performance numbers flip-flopping from poor to great in as little as one additional month in the period.

It also puts a spotlight on the cost of underperforming in good years in order to be protected during bad years—and this not a great point to focus on for risk managers. Strategies that rely on market protection using put options have long suffered under this type of scrutiny. Put strategies can provide highly effective protection against declines in equities. But to hold puts all the time in order to maintain that protection is to suffer a significant underperformance over time due to their high relative cost. As a result, the strategy of using protective puts through all scenarios is seldom, if ever, used, even though strategies that use puts in spreads or collars can be much more cost-effective. Risk managers using other ongoing protection strategies would not want to be painted with the same brush as put option strategies.

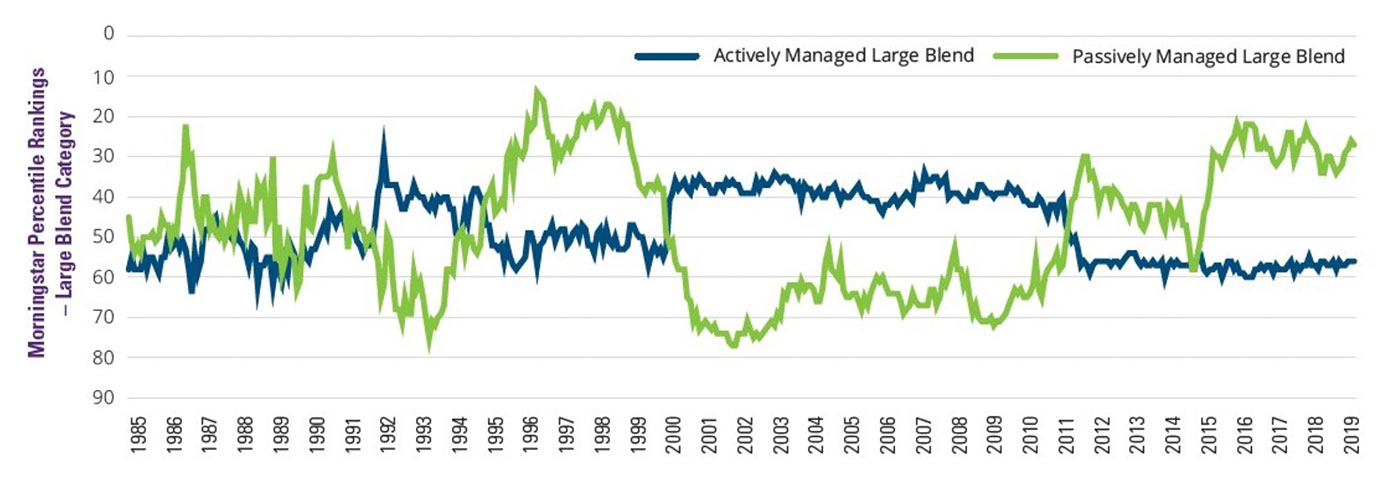

One way to get around the time challenge is to show rolling-period performance. Hartford Funds, using Morningstar data, conducted a 2020 study of rolling 36-month periods over 34 years to produce the following graph on active versus passive management. (Remember from the previous discussion, however, that “active management” defined solely by the Morningstar categorization may be somewhat misleading.)

The results portray a cyclicality of performance superiority between “active” and “passive.” It might be worthwhile for risk managers to show their performance in this manner rather than in single, cumulative time frames while focusing their narrative on lower volatility and risk mitigation.

Sources: Morningstar and Hartford Funds, 2/20

As the Cerulli study showed, risk management can be a powerful part of investor expectations, particularly for the high-net-worth audience. A more in-depth focus on specific risk-management techniques should benefit everyone involved, allowing managers with a formal risk-management approach to make that a prominent part of their narrative, thereby providing greater transparency and better alignment between risk managers and risk-sensitive investors. This would enhance the overall validity of risk-management strategies and could lead to improvements in the way managers are categorized as well.

But risk management can refer to a wide range of implementations by managers, which, in turn, yield a variety of results in different market environments. Thus, it will also require managers to be explicit about their risk-management strategies and more disciplined than they might otherwise be about the use of risk-management tools and techniques in the future.

So what does this say about the case for risk management?

Clearly, there is a case for risk management, but it currently suffers from vague arguments, lack of categorical performance measures, and murky definitions. To enhance the case, two overriding concepts need to be clarified: first, that “active management” does not equate to “active risk management”; and second, that “formal risk management” needs to be distinguished from risk mitigation through simple, or equity-only, diversification. Both of the latter approaches have a place, but investors should understand the difference, and managers should be able to articulate it.

The desire for risk management is deeply embedded in the psyche of many investors, and it may be the one core aspect of active management that passive management cannot compete against.

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.