Investing is about managing stress—as well as performance

Investing is about managing stress—as well as performance

While there is no way to eliminate all market risk, an actively managed portfolio with an emphasis on risk management may produce less stress than a passive portfolio for both advisors and their clients.

In my 35-year career in and around Wall Street, I have seen the markets exact a personal toll on many investors, both retail and professional. Driven by subliminal inner forces, many people have allowed the markets to push them to extremes and, unfortunately, have done harm not only to their portfolios but also to their health and well-being as a consequence.

A focus on investment strategies that avoid, minimize, or mitigate these extremes can provide more advantages—both in realized long-term performance and behavioral benefits—than a completely passive portfolio. It does so in part by eliminating the negative actions people (including advisors) often take under stress.

An extreme example of stress

The following is a true story, and one I doubt I will ever see again.

Early in my career, I was an options coordinator for a major wire house in New York. The CBOE had recently opened its doors, and options trading was exploding. Since stocks had languished for months, the idea of writing naked strangles on the OEX (selling both uncovered calls above the market and puts below) was all the rage at this firm. A large options trader in the retail system (let’s call him Joe) was writing naked OEX options for many of his clients. The strategy performed rather well for months. Then came a stock explosion to the upside, and with it a return of volatility. Losses piled up quickly, and the stress of managing portfolios with naked options skyrocketed.

One afternoon, I received a call from Joe’s office manager. Joe had just been carried out of the office by paramedics with an apparent heart attack. As they put him on a stretcher, he was unable to speak but motioned for a pen and paper. The manager read his note to me. Even as they were trying to save his life, Joe was trying to put in an order to cover OEX call options!

Joe may have been an exception due to the extreme risk of his option positions, but even a plain vanilla portfolio of stocks will cause people stress. Financial advisors often believe that their job is to take the stress of investing off the client’s shoulders, but that can turn into an unhealthy premise for many advisors. For one thing, advisors can’t remove all of the market risk from stock portfolios, no matter what their strategy or how closely they monitor it. This is especially true for advisors who primarily rely on passive portfolio allocations since the premise behind such strategies is to hold on through the storm, no matter what level of market risk they are facing. For another, they cannot simply absorb the stress that a client might be feeling. Clients can still generally feel the effects of portfolio stress even when they believe the advisor’s tools for risk management are somehow going to keep them out of trouble or when the advisor is counseling them to just keep calm through any turmoil.

The nature of stress

We know stress mostly by its physical manifestations: headaches, nausea, insomnia, elevated blood pressure, and sometimes even chest pains. We also know that while it is part of a highly useful alarm system that is key to human survival, it is unhealthy for us to carry too much of it around with us for too long.

Stress is not just behavioral, it is chemical. The American Psychological Association defines stress as the “automatic response developed in our ancient ancestors as a way to protect them from predators and other threats. Faced with danger, the body kicks into gear, flooding the body with hormones that elevate your heart rate, increase your blood pressure, boost your energy and prepare you to deal with the problem.”

So, when subliminal sensory perceptions decide that we are in danger, they automatically invoke a protective protocol that unleashes a chain reaction of chemical and neurological events geared to stir us to action and making us more capable of doing so—hence the urge to panic and sell when things look vulnerable in the stock market. It is a visceral human reaction.

It has been firmly established by researchers that the chemical reactions in the human brain to basic instincts such as sex, food, and survival are also stimulated by money. Dopamine, for example, the chemical neurotransmitter that passes on messages to neurons about rewards and pleasure, can be associated with the idea of making or winning money. So it should be no surprise that the idea of losing money also sets off basic chemical reactions within humans through neurotransmitters such as adrenaline and cortisol. The stimulus that sets off these chemical reactions is stress.

The problem is that our biological sensors do not distinguish between a physical attack, a dress-down from one’s boss, or a stock market tumble. With stocks, they kick in not just when we actually see the market decline but can also show up when others even suggest that it might. This chemically induced urge to action is responsible not only for unhealthy levels of stress but for the pervasive underperformance of self-managed stock portfolios.

Headwinds-tailwinds asymmetry

Classic financial theory offers diversification of our holdings to reduce the idiosyncratic risk of individual securities, but that is no antidote for market risk, without also removing your opportunity for gain. Consequently, many advisors and wealth managers, along with their clients, are forced to accept the ups and downs of the market and to take a long-term perspective on investing. This, however, flies in the face of human nature when the market declines, and even in climbing markets. Long-term optimism is simply no match for short-term loss aversion and fear of uncertainty.

Exacerbating the problem is a psychological effect called “headwinds-tailwinds asymmetry.” We tend to relax when the wind is at our backs and things are going well. (Running and cycling enthusiasts know this well, hence its name.) But when we face problems of any kind (a headwind), it is natural to become anxious. The reaction is asymmetrical in that the anxiety occurs with every headwind, no matter how infrequent, while there is no offsetting joy during tailwinds since we tend to expect that.

For investors, this lopsided effect causes anxiety almost every time the market goes down, despite the long-term trend moving up. It is pervasive, even if only slight in magnitude, but it can also be cumulative over time and increase along with the size of the portfolio and other factors. If you are invested in stocks, it is almost impossible to be totally immune to headwinds-tailwinds asymmetry. The anxiety of declining days subtly builds up in us. Abnormally large sell-offs cause a proportionately greater reaction, and the effect can remain with us well beyond the point when the market has recovered the loss. It is the slow buildup of anxiety that leads to stress.

Coping with the unavoidable

To address the problem of stress, we can counter the body’s reaction to it, or we can reduce or eliminate the cause. Today’s emphasis on good health offers a bevy of stress-management techniques that generally include relaxation activities such as yoga, meditation, tai chi, or almost any type of exercise. So that type of advice is readily available. But how can an advisor reduce the cause of stress to clients in the first place?

Part of the fear that accompanies ownership of a stock portfolio is the fear that an investor has little or no control over what happens next. For a passively managed portfolio, this fear creates a continuous dilemma about when, if ever, to sell, creating a subsequent stress about when to repurchase. This gets more complicated through loss aversion, regret, hindsight bias, and a host of other stress-producing biases.

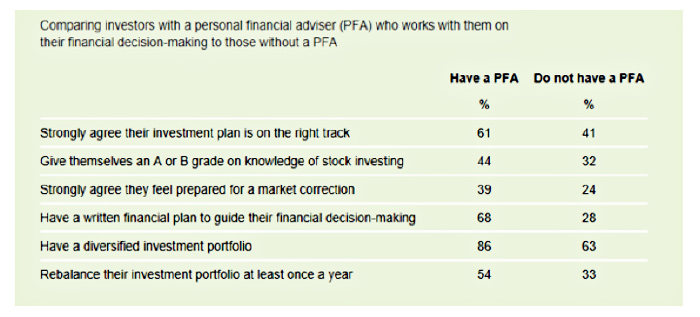

Investors with personal financial advisors certainly have an advantage in this regard versus self-directed investors. Yet, as seen in a 2017 study from Wells Fargo and Gallup, even those investors with advisors still stress out over the market—only 39% “strongly agree that they are prepared for a market correction.”

TABLE 1: ADVISORS HELP ALLEVIATE CLIENT CONCERNS, BUT CAN DO FAR MORE

Source: Wells Fargo/Gallup Investor and Retirement Optimism Index, July 28–Aug. 6, 2017.

This is where active management can add value beyond performance. Active management reduces the fear of lack of control. Active managers tend to shine in down markets because they know how to manage a portfolio or strategy throughout the process rather than try to time a wholesale liquidation and re-entry, which almost everyone will get wrong. Thus, by its very nature, active management provides a solution less prone to stress than passive. In addition, just knowing that someone is managing their portfolio during periods of declines and elevated market risk can assuage the fears of many clients and reduce their stress.

Next, advisors need to recognize the natural focus of clients on the negatives and do their part to redirect that. Part of headwinds-tailwinds asymmetry holds that if clients are examining the performance of their portfolio, they will tend to focus more on the declining stocks or sectors than advancers. Unfortunately, the media will also, so advisors need to be prepared with the offsetting positives when talking with clients, focusing on the big picture of performance over several years, not what happened yesterday, last week, or last month. A market sell-off of 5% will induce much more fear from the perspective of the most recent high than it will from the perspective of the past 12-months’ performance.

Lastly, don’t underestimate the power of communication with your clients in reducing stress. In many cases, clients just want to know what you are thinking or planning in order to feel less fear. You will likely find your own stress reduced through such conversations as well.

Stress is a silent and sinister enemy. It can wreak havoc on your health, your performance, and your clients. It certainly might be worth taking that morning yoga class several times a week, but it is probably a more effective plan to help reduce stress through sound portfolio-management practices and strong client relationships. Active investment management and active communication with clients will go a long way toward this goal.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Proactive Advisor Magazine. These opinions are presented for educational purposes only.

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.

Recent Posts: