While the billionaire investor is known for taking a long view on the companies he owns, he makes it clear in this year’s letter to shareholders that his commitment is not without borders (excerpt taken from page 20):

“Sometimes the comments of shareholders or media imply that we will own certain stocks ‘forever.’ It is true that we own some stocks that I have no intention of selling for as far as the eye can see (and we’re talking 20/20 vision). But we have made no commitment that Berkshire will hold any of its marketable securities forever.”

Even in the absence of such a declaration, the sizable partial divestiture of Berkshire’s IBM stake (the firm still holds 54 million shares worth approximately $8 billion) in no way contradicts Buffett’s investment philosophy—which makes all of the hoopla a bit misplaced. If the investing legend had knee-jerked to selling a third of his holdings based on rumors or ominous market undercurrents, the sale would be worthy of the pundit noise. The circumstances of Berkshire’s sale, however, are nothing of the sort.

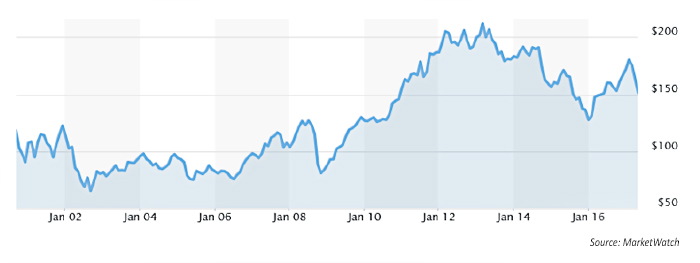

Berkshire made its first investment in Big Blue back in 2011, betting on the company’s expertise in information technology services and on then-CEO Sam Palmisano’s shift away from hardware toward service and software (for which he was making aggressive stock buybacks). When Ginni Rometty took the helm in 2012, she first slowed then ended the buyback program in 2014, causing a significant drop in share price. Buffett stayed the course, however, due to his belief that the intrinsic value of his investment would recover and exceed any losses incurred—a move entirely consistent with his philosophy.

FIGURE 1: IBM SHARE PRICE (2001–2017)

When IBM’s efforts to expand its cloud and software services didn’t meet expectations and failed to offset declines in some of its major business operations, concerns were raised about the company’s ability to compete—a real sticking point for Buffett. In an interview with CNBC, he said, “I don’t value IBM the same way that I did six years ago when I started buying.” He added, “I think if you look back at what they were projecting and how they thought the business would develop, I would say what they’ve run into is some pretty tough competitors.” Buffett summarized as follows: “IBM is a big, strong company, but they’ve got big, strong competitors too.”

Competition is a cornerstone of the Buffett investment philosophy: Two critical and interrelated qualities he looks for in companies are an “enduring moat” and a “durable competitive advantage.” Having an enduring moat means a company has some quality that makes it almost impossible for a competitor to overtake it—regardless of how much money they’re willing to spend in the process. Think Coca-Cola, a company that boasts huge sales volume all over the world and also has incredible brand recognition. Durable competitive advantage takes this a step further and refers to a dominant, virtually impenetrable market share.

When circumstances change, as they did with IBM, Buffett takes notice. In recent years, for example, he sold most of Berkshire’s stock in Wal-Mart, citing increased competition from Amazon and other online retailers. Similarly, Buffett took a dim view of IBM’s inability to keep up with the cloud-related technology offerings of its competitors.

So, while the shrinkage of Berkshire’s stake in IBM seemed like big news, it is entirely consistent with the way Buffett does business and invests. He adheres to a consistent, disciplined review process and rethinks his position if fundamentals deteriorate.

At Validea, one of the key decisions we made early on was to run our model portfolios, which are based on stock-picking strategies of great investors, with frequent and set rebalancing periods. We combat the emotional side of investing by allowing our models to select top-rated stocks through quantifiable measures of share valuation and operating strength, and also to maintain a strict rebalancing approach. This forces the portfolios to sell stocks when scores fall and to replace those names with better-scoring opportunities.

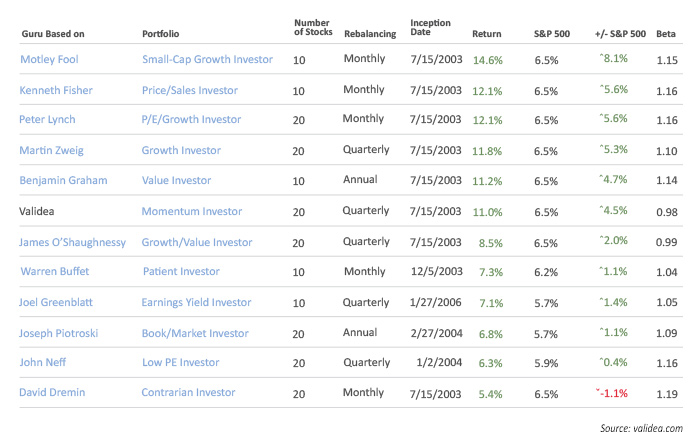

In the following table, you will see all of the models I track on Validea and the optimal performing strategies using 10- and 20-stock models rebalanced either monthly, quarterly, or annually. Since 2003, when I began tracking most of these models, the more frequently rebalanced portfolios have tended to outdo those that are rebalanced annually. It’s important to note that, for many investors, frequent checking and/or tweaking of their portfolios leads to decreased performance. Our data shows, however, that performance can be enhanced when models use disciplined analysis of fundamentals and apply a process that buys better-scoring stocks and sells lower-scoring names.

Here are two key lessons:

- Try to develop a “sell” discipline—a non-emotional, systematic way to review your portfolio holdings. If your rationale for buying the stock no longer exists, you may want to consider selling it.

- There is opportunity cost associated with either holding stocks in your portfolio or holding cash. If you sell, it’s a good idea to have a short list of buy candidates or follow a systematic buying approach like the one we use for the portfolios.

The results speak for themselves.

TABLE 1: COMPARISON OF ‘GURU-BASED’ VALIDEA STRATEGIES

This article first appeared at nasdaq.com on May 16, 2017. The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Proactive Advisor Magazine. These opinions are presented for educational purposes only.

John P. Reese is co-founder of Validea Capital Management. He is the manager of Validea Capital’s active equity ETF and separate accounts. Mr. Reese is the author of “The Guru Investor: How to Beat the Market Using History’s Best Investment Strategies.” He is a graduate of MIT and Harvard Business School and holds two patents in the area of automated stock investing. Follow John’s thoughts and ideas at www.validea.com/blog or on Twitter at @guruinvestor.

John P. Reese is co-founder of Validea Capital Management. He is the manager of Validea Capital’s active equity ETF and separate accounts. Mr. Reese is the author of “The Guru Investor: How to Beat the Market Using History’s Best Investment Strategies.” He is a graduate of MIT and Harvard Business School and holds two patents in the area of automated stock investing. Follow John’s thoughts and ideas at www.validea.com/blog or on Twitter at @guruinvestor.