The sum of all our investing fears

The sum of all our investing fears

FOMO (fear of missing out), though a common theme in financial news, is only one side of what may be the single most powerful emotion in investing.

FDR nailed it in his 1933 inaugural address. People have echoed his words on fear ever since, though most truncate the original statement, removing an important part. His actual words were “… the only thing we have to fear is fear itself—nameless, unreasoning, unjustified terror which paralyzes needed efforts to convert retreat into advance.”

He wasn’t talking about war. He was talking about wealth and money. It was the height of the Great Depression. FDR recognized that the financial losses of the Depression were causing people to feel “unjustified terror,” preventing them from behaving rationally and effectively addressing their circumstances. He was ahead of his time in understanding how financial fear impacts behavior.

A half-century later, Israeli psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky linked decisions relating to financial risk with those made under life-threatening conditions on a battlefield. They demonstrated that similar biases characterized both, ushering in the field of behavioral finance as we know it today. That doesn’t mean we run for cover whenever the market sells off, but it does mean that our reactions in those circumstances share similar mechanisms in the brain.

Neuroscientists later confirmed that the brain chemistry associated with physical danger closely resembles that of financial danger. This shouldn’t be surprising—our behavioral DNA evolved over hundreds of thousands of years when survival depended on reacting to threats, long before the concept of money even existed. As a result, our brains respond to perceived threats similarly, whether they come from a tank or a computer screen.

FDR was concerned that widespread fear would paralyze people, preventing them from taking necessary actions to remedy their situations. His concerns were valid.

Among the many emotional biases humans exhibit when making risky decisions, fear is among the strongest and most prevalent. It is innate, managed by an anatomical device—the amygdala—that emits chemicals that make us feel that fear. Fear is part of our DNA and is surprisingly common in our interactions with financial risk. And yes, it influences both professionals and everyday investors, albeit to varying degrees.

What we often fail to realize is that fear is always present where risk is concerned. Panic selling and FOMO buying are among the more evident extremes, but risk of any kind can have an impact on behavior. We can commonly see that when stocks sell off for reasons not directly related to the fundamentals of the markets, such as news of Russia launching a missile attack on Ukraine.

Insights on fear from an afternoon climb up El Capitan

A rare cadre of individuals—made rarer still by their survival rate—overcomes fear that most of us find unimaginable. Their insights on dealing with fear can be highly valuable. Alex Honnold is one such individual. Honnold has the uncanny ability to suspend fear while clinging to vertical rock faces several thousand feet above the ground with just his fingers and toes—no ropes, no safety net, and no way to get off a sheer cliff other than to keep climbing.

One of Honnold’s most prominent accomplishments was free-climbing Yosemite’s 3,000-foot rock monolith, El Capitan, earning him global acclaim. What confounds most people about his feat is how he deals with the life-or-death fear inherent in every step, every loose rock, and countless unforeseen variables, any of which could end his life in seconds. His approach has profound implications for investors, advisors, and managers. While they may never scale El Capitan, they face thousands of risky decisions throughout their lives.

Honnold admits he is far from fearless. (He has even undergone medical tests designed to see if his amygdala functions properly.) Instead, he controls his fear through confidence in his technique, intense risk analysis, and acute awareness of his limits. For Honnold, this meant completing dozens of solo climbs beforehand, including several up El Capitan (with ropes first), studying his intended path and alternatives for months, and leaving no part of his ascent unplanned. It wasn’t a matter of simply relying on his skill to figure it out along the way. He knew exactly how he would make every inch of the climb.

How many investment pros and financial advisors can say the same thing about their endeavors? Have you thoroughly studied the assets you plan to trade? Are you solid on your technique? Do you know how you will handle different potential scenarios? Or are you relying largely on experience and instincts to tell you what to do or when to do it?

Even if your instincts are superior, your technique well-honed, and your assets well-studied, is that enough to ensure success? What exactly will happen if unexpected news comes out, the market sells off, or your stocks simply take an unanticipated dip? How will the fear of such scenarios affect your decision-making?

Honnold has a healthy respect for fear. He says, “Fear is an interesting counselor. There are times when it’s incredibly helpful, warning me that I’m not quite ready for a particular challenge.” For Honnold, fear is an ally, not an enemy. He adds, “The key to managing fear is to remember that it’s always driven by a kernel of truth.”

Investors, advisors, and portfolio managers face risk almost every trading day. While not life-threatening, these risks can threaten careers, clients, or wealth—and exposure to these risks can certainly affect behavior (and subsequent performance) over time.

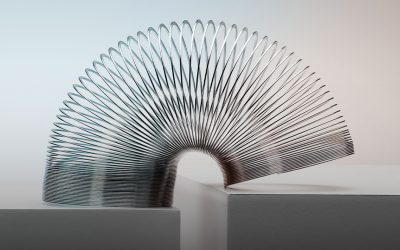

Even if you are confident in your strategy’s ability to produce positive risk-adjusted returns over time, financial risks rarely unfold in a smooth, predictable manner. They rise and fall intermittently, and when they rise, they affect our decisions, rationale, and execution. This is why, in general, investors are notorious for selling at the wrong times and being too afraid to buy during the best opportunities.

A climber may have proven skills and detailed knowledge of the mountain, but unexpected events can test their ability to adapt under heightened fear and avoid a potential catastrophe. For instance, 1,000 feet into his iconic climb, Honnold got scared about the next section and decided to change his path. The change worked but planted self-doubt in his mind for the remainder of his climb.

For investors or managers, similar deviations from their planned strategy can jeopardize their expected long-term performance. The fear of that can create a negative feedback loop that wreaks havoc on consistent adherence to a well-planned strategy.

Facing our fears in investing

When the market is closed and you’re in a calm place away from your screen, take some time to identify your most significant fears, how and when they affect you, and how you plan to regain your momentum afterward. You may quickly realize how many forms of fear you face regularly.

Common fears for investors, beyond the fear of loss, include the following:

- Fear of underperforming (and, for professionals, the career consequences that might follow)

- Fear of losing self-confidence

- Fear of regret

- Fear of missing out, such as missing upside or not participating in a “hot” market sector

- Fear of idiosyncratic risk (having the right direction but the wrong stock)

- Fear of buying too high

- Fear of not selling at the right time

- Reputational fear

- Fear of unknown risks

Not all of these fears may be obvious. You might feel angst or stress without realizing that a specific fear is the root cause. Fear can just as easily (and even more frequently) emanate from your subconscious brain. While you consciously consider a trade, your subconscious mind processes far more than you are aware of—much like when you drive a car. Your conscious mind handles the overall route and objective, but it’s actually your subconscious that watches for traffic signals, signs, and surrounding vehicles.

If you want to dig deep enough to identify your own fear demons, try keeping a journal for a while and monitoring your fears. Many fears do not result in immediate action but build up over time. It would be revealing to know what these are and when you are experiencing them, as that might reduce the fear of carrying a position too long or waiting too long to acquire one.

This exercise isn’t just about self-analysis. Its purpose is to determine which fears you can avoid and which ones you cannot. Beyond reducing your ongoing stress, you should develop a plan to address both known fears and unknown fears when they pop up. You can likely mitigate at least some fears or even avoid them entirely. For the ones you cannot avoid, you can then develop a plan. If you are a financial advisor, the exercise should incorporate your clients as well, since managing their fear is part of why they pay you.

There are multiple ways to reduce your ongoing fears. It could involve a different diversification plan, an options hedge, or substituting assets with lower risk. You might consider placing assets under active management with third parties who use rules-based, algorithm-driven strategies that can remove emotion from the decision-making process altogether. Alternatively, deeper analysis and developing specific buy or sell points in advance could help.

For the unavoidable fears that accompany risk assets, you may just need to look inward. Many investors and advisors use techniques such as meditation to reach a less stressful state of mind.

For someone like Alex Honnold, fear is a necessary evil. Without it, he wouldn’t feel safe enough to climb at all. He sees fear as the protective mechanism it is—the subconscious safety net that catches what the conscious mind may not and prods you to stop and think about something that might be a danger. For an investment manager, the goal should be similar: to understand how fear influences your behavior and turn it into a strength instead of a hindrance.

Honnold acknowledges that he sometimes feels overwhelmed by fear—but it’s not while he’s climbing. It’s when he’s speaking in public. Apparently, hanging on by his fingertips hundreds of feet above the ground doesn’t faze him, but standing on a stage in front of an audience frightens the heck out of him. It seems we all have different fear crosses to bear.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and the sources cited and do not necessarily represent the views of Proactive Advisor Magazine. This material is presented for educational purposes only.

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.

RECENT POSTS