The conundrum of growth: Why it’s an opportunity for active managers

The conundrum of growth: Why it’s an opportunity for active managers

Projecting corporate growth and deciding how much to pay for it remains a scattered and often subjective task in stock valuation. Does this provide opportunity for active managers who can apply a more disciplined process and a more nuanced appreciation of growth?

Studies of horse wagering discovered a long time ago that race fans tend to consistently overbet the favorites, thereby lowering the odds and the subsequent payoffs on them to the point that it was a decidedly losing proposition to bet the favorites regularly.

Sure enough, market researchers have shown that investors share a similar bias toward their favorites—growth stocks. Researchers have determined that over a very long time, investors tend to overpay for growth stocks to the point of rendering it a better bet on a risk-adjusted basis to buy the unloved, low-growth stocks—also known as value stocks.

Figuring out how to value corporate growth, measuring that growth against other companies on a risk-adjusted basis, and then reconciling all of that with how the market is valuing that growth (or will value it in the future) may be among the biggest conundrums investors and managers face.

The good news is that conundrums like this represent the type of market inefficiencies on which active management thrives.

Managers who select individual stocks can fine-tune their approach to the different types and rates of growth across companies, and those who primarily use mutual funds and ETFs can look deeper into the way their fund managers approach growth to sidestep the typically overgeneralized approach to growth that many fund managers exhibit.

Mutual funds largely define growth stocks in relative terms as those that grow faster than the economy or simply faster than other stocks. Many use narrow and highly generalized criteria for selecting their growth universe, like industry classification and earnings growth, and then hold these stocks over a very long time under the assumption that companies deserve to retain that status forever.

In addition, competitive pressures often create “must-haves” that funds will buy or hold, regardless of where those stocks might be in their growth cycles. Such classifications may miss, understate, or ignore the full spectrum and diversity of growth characteristics that companies actually exhibit. How many growth funds held on to Microsoft stock during the years 2011–2019 while earnings were actually declining? And how many missed Amazon’s decade of price growth because the company hadn’t yet generated positive earnings?

That’s not to say exploiting growth inefficiencies is a slam dunk. Valuing growth has myriad complications. On what criteria should you measure growth in the first place—earnings, revenue, assets, subscribers? How do you value growth that has yet to be monetized? How do you realistically project growth for years into the future? How do you account for growth that isn’t constant or continuous? How do you measure growth for products that never existed before? And how do you account for companies that exhibit the magic of accelerating growth?

No one has all of these answers at their fingertips, but that, of course, is what makes growth valuation so inefficient.

For a somewhat extreme example, a recent Barron’s article cited 10 analysts’ projections on Tesla stock varying from $300 per share to more than $2,300. Tesla isn’t a company with esoteric technology nobody can understand. It has physical product and manufacturing facilities. Yet even with that, the spread between low and high estimates is nearly a factor of eight. That’s enough price inefficiency to drive an electric 18-wheeler through.

For something so central to the core of why we invest in stocks, the industry’s approach to growth is still in many ways overgeneralized, oversimplified, and overly sensitive to enticing narratives. Growth based solely on earnings is either useless or inappropriate for a major portion of companies. Assuming growth to be a constant and projecting it based on industry averages can prove decidedly inaccurate. PEG (P/E to growth) ratios are calculated on a projection of growth that only accounts for the next few quarters. And classifying stocks as either growth or value is arbitrarily binary.

For all the attention the market gives to every last nickel of a company’s earnings, growth is considerably more critical to stock price since growth is what feeds the multiple that the market places on earnings to establish price.

Among other things, the multiple fundamentally accounts for the quality and consistency of earnings, the economic environment, and industry differentiations, and, in large measure, it represents the future expectation of growth in earnings for years to come. With price-to-earnings multiples at times reaching 30X, 50X, or even 100X, the mathematical impact of growth on price dwarfs that of the earnings themselves, and that’s hard to ignore.

You would think that for a concept so central to stock investing, we would have many well-defined distinctions for different types of growth, rates of growth, growth-to-risk measures, life-cycle growth patterns, and so on. The fact that we don’t should represent an opportunity for active managers who can optimize stock, fund, or ETF selection based on more relevant and discreet aspects of growth coupled with a better understanding of how the market tends to value it.

That’s not to say that the market is completely naive about growth or that analysts don’t figure it into their estimates. It simply means that growth considerations are not an exact science and that pricing anomalies may be hiding in plain sight—where growth attributes are oversimplified or taken for granted. Managers can focus on a number of areas where growth inefficiencies make their way into pricing.

By their nature, some companies might well exhibit reasonably steady growth rates over long time periods. A supermarket chain or a bank, for example, might adhere closely to the growth rates of the population in the areas they serve.

But many others have to front-load investments before opening up a new production facility, launching new products, or introducing new technologies. In these situations, earnings growth can become a highly irregular variable, surfacing in fits and starts dependent on factors as disparate as new technologies or a new CEO. The most exaggerated of these situations would be companies like biotech firms working for years on a disease cure or younger companies plowing all of their revenues for years into building out their infrastructure.

Too often, such growth irregularities are glossed over with average long-term growth rates that will vary wildly between under- and overestimating the true growth rates of the company or its earnings. An active manager might be able to find high-growth “sweet spots” hidden in the averages. The market will generally anticipate future expected growth, and stock prices may rise faster than actual growth for years leading up to a high-growth sweet spot. Such periods might yield impressive price appreciation, but anticipation is by nature somewhat speculative and, therefore, arguably carries a higher risk. When the earnings growth begins to materialize, price appreciation may underperform the actual growth rate in earnings, but it may also carry less risk. As a result, earnings growth spurts could provide opportunities for strategically advantageous risk-adjusted periods of ownership.

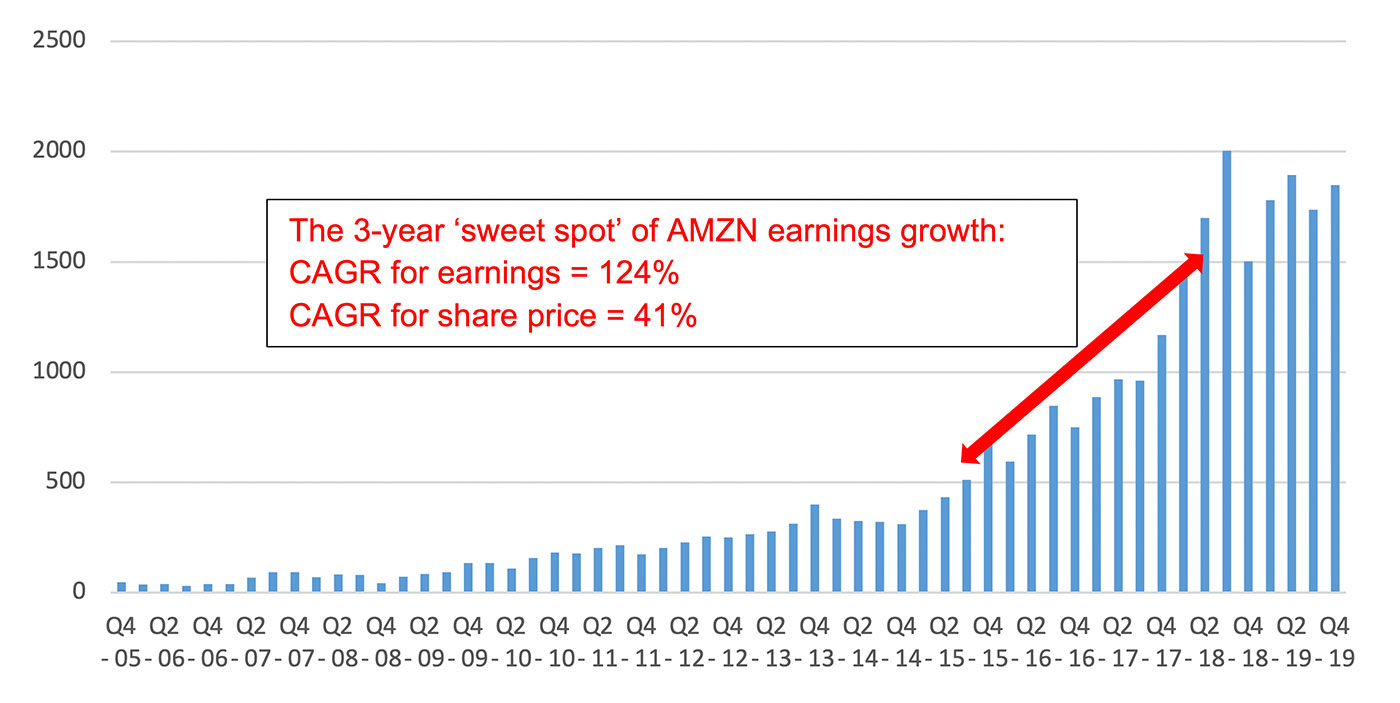

Amazon (AMZN) provided such an opportunity as it moved into its impressive sweet spot in earnings growth during 2015. For the prior 10 years, AMZN shares had been appreciating at roughly a 30% compound annual growth rate (CAGR) amid negative or paltry earnings. This appreciation was almost all based on revenue growth and the anticipation of future earnings, once the company slowed down on building infrastructure.

When the earnings spigot opened, they exploded upward for three years, realizing a CAGR of 124% per year during that period. Price continued its run as well, and, while underperforming the earnings growth rate, moved up at the healthy rate of 41% annually. Many investors may have been disappointed the stock didn’t appreciate even more, but 41% growth each year for three years is a very attractive sweet spot to capitalize on, especially considering the reduction in risk associated with real earnings growth.

Source: Multpl.com

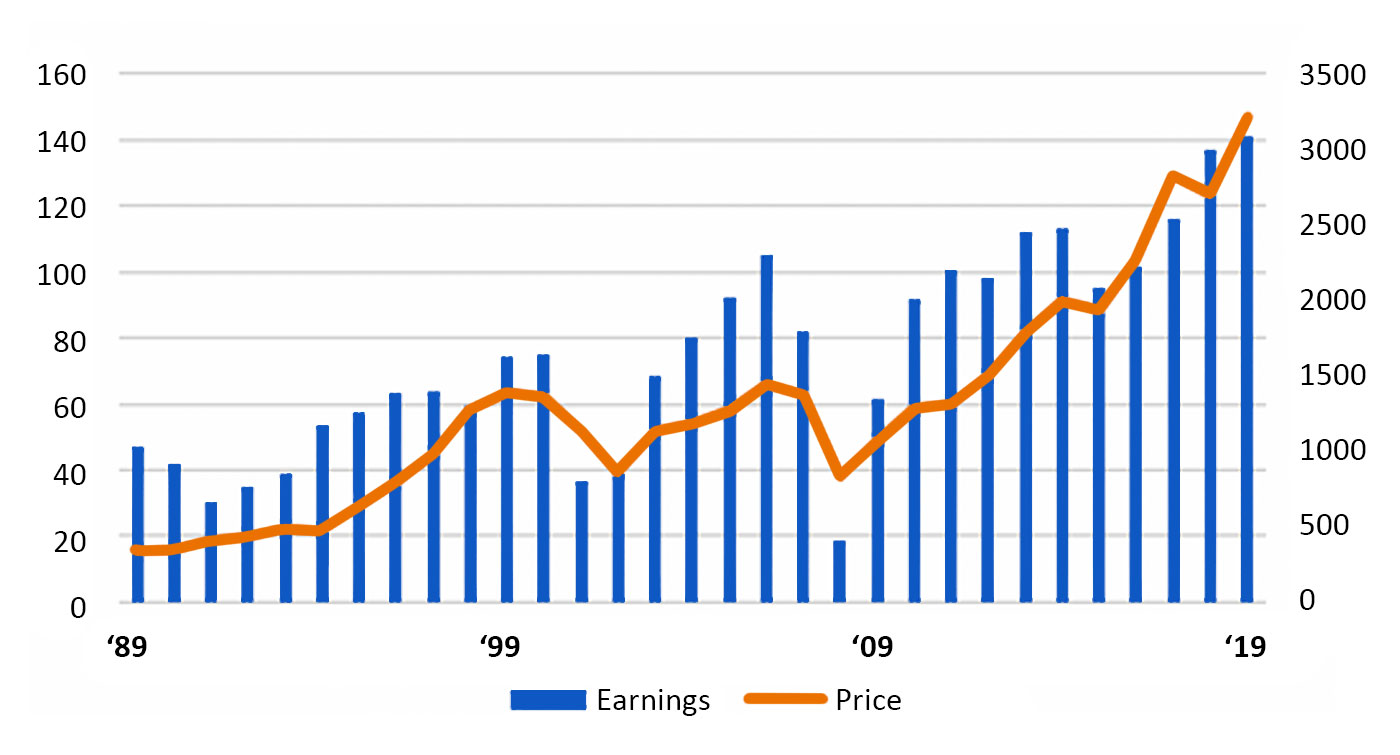

Complicating the irregular growth patterns of individual companies are the overlays to growth that come from the economy as a whole, such as interest rates, employment, and so on. The variation in S&P 500 earnings from year to year shows that the earnings of our top 500 public companies as a group vary extensively from year to year and that the price of the group’s shares tends to smooth out those irregularities.

Figure 2 presents S&P 500 earnings versus price for 1989–2019, showing how price maintains less volatility than earnings growth might suggest.

Figure 2: S&P 500 EARNINGS VS. PRICE (1989–2019)

Source: R. Lehman, market data

Financial textbooks tend to use constant growth rates for simplicity in calculating discounted cash flow valuations, rather than the dynamic growth rates that would be much more realistic but cumbersome to calculate. Many analysts and fund managers defer to constant growth rates as well, perhaps, in part, to simplify their task or because they usually don’t have the inputs they need to create meaningful growth rates more than a year or so into the future. Corporate growth, however, is inherently a dynamic variable subject to a wide range of contributing factors that include changing markets, competition, new products, and new technologies.

Assumptions about growth constancy may also be obscuring a new type of growth entirely–the kind we call “viral,” which is often exhibited by technology-related companies. Classic economics has always assumed that a company can grow rapidly in the beginning, peaking eventually at a growth rate constrained by competition, market size, and other factors, and then ultimately succumbing to diminishing returns. Many companies seemed to turn that idea upside down in the late 1990s, and their actions led to a new perspective on the former growth paradigm.

In 1996, W. Brian Arthur penned an article for the Harvard Business Review called “Increasing Returns and the New World of Business.” Arthur explained how for more than a century our understanding of economics was “… based squarely on the assumption of diminishing returns: Products or companies that get ahead in a market eventually run into limitations, so that a predictable equilibrium of prices and market shares is reached.”

Arthur claimed that while this understanding was adequate for smokestack industries, the 1990s were ushering in a distinctly different type of business—one that could create situations where a rate of growth could actually increase over time. In Arthur’s words, “Increasing returns are … mechanisms of positive feedback that operate—within markets, businesses, industries—to reinforce that which gains success or aggravate that which suffers loss.” And the internet boom of that decade was producing numerous examples of this premise in action.

Arthur postulated, “If a product or a company or a technology … gets ahead by chance or clever strategy, increasing returns can magnify this advantage.” One can readily appreciate what Arthur’s premise could do to stock prices and P/E multiples in companies that are fortunate enough to fall into the increasing return category. In fact, it melds well with the narratives of the dot-com explosion that claimed “this time it’s different” and led to the highest P/E ratios ever for the S&P 500.

Over the last two decades, the euphoria of the ’90s has been toned down, but a core of internet companies has matured to the point where they are again demonstrating Arthur’s foresight. The manifestation of Arthur’s increasing returns principle easily shows up in companies such as Facebook, Netflix, or Zoom, where the companies see their revenues exhibit exponential growth, which doesn’t necessarily come only at the very beginning of their growth cycle.

While growth is the ultimate object of investor affection, investors and fund managers may be overpaying for growth that has yet to materialize, holding growth stocks way beyond their sweet spots. In addition, they may be once again paying too much for growth as they did in the ’90s, or too little for growth that is decidedly different from the type of growth of the last century.

The upshot on horse racing is that playing contrarian and betting on all the long shots isn’t a winning strategy either. People overbet those also. To systematically win at the horses, a bettor needs to avoid both extremes and focus instead on those races in which the odds and the handicapping were deemed to give them an advantage.

For investment managers, the parallel would suggest that a staid portfolio stacked with either growth or value stocks is not a guaranteed market-beating strategy. The manager who does the proper handicapping, selects the right growth stocks or funds to own at the right time in their cycles, and discerns when the price-to-growth parameters are favorable, might have the winning approach.

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.