Understanding the relevance of risk-adjusted returns

Understanding the relevance of risk-adjusted returns

While clients might profess a willingness to endure large portfolio drawdowns, when losses become a reality, their attitudes and behavior often change swiftly. Explaining the relevance of risk management and risk-adjusted returns is one of the most important tasks facing all advisors.

There have been a number of popular media articles lately proclaiming that active management is less than ideal for investors. The articles claim, on average, active management strategies don’t outperform passive strategies—and there is some data to corroborate such claims. For example, on average, hedge funds have generated negative alpha on a rolling five-year basis.

Similarly, only 23% of actively managed large-cap core mutual funds have outperformed the S&P 500 year-to-date. Unfortunately, the media lump together the diverse set of hedge funds, stock-picking mutual funds, and multi-manager/asset/strategy portfolio approaches designed for risk-adjusted returns, even though the differences are striking.

Unsurprisingly, the critics of active management suggest a passive, buy-and-hold portfolio mixing traditional asset classes (e.g., stocks, bonds) in proportions designed to meet the needs of specific investors. And in the midst of the bull market we have experienced for the past five years, this type of passive strategy has indeed worked well. But does that mean active management should be abandoned?

For many investors, the answer is probably “no,” particularly when considering holistic portfolio approaches as mentioned above. To fully appreciate why, we must look not only at returns but also at the risk side of the equation.

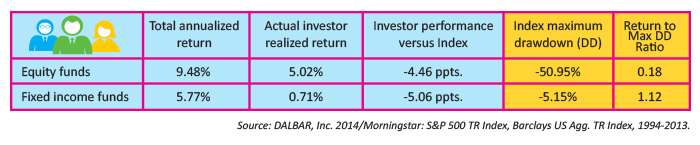

The 2014 DALBAR Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior Report paints a vastly different picture of passive returns. Despite the theoretical performance of holding passive funds, over the last 20 years returns realized by investors have fallen severely short. The table below highlights the problem.

Of course there have been many ups and downs over the last 20 years, so what about the more recent past? Well, according to the same report, results for the past three years have been getting worse—equity fund investors have lagged the S&P 500 return by 5.31%, with the gap expanding each of the last three years.

Why does this happen to investors? The DALBAR report mentions that “the major cause of the shortfall has been withdrawing from investments at low points and buying at market highs.” What this behavior likely comes down to is that investors simply can’t follow the passive strategy. It sounds counterintuitive, but despite the seeming simplicity of the passive strategy and its recent outperformance, passive is still a strategy. And just like active strategies, the rules must be followed.

Equity returns for individual investors consistently lag the S&P 500.

What does all of this have to do with risk-adjusted return? A lot, actually. Let’s first define the term “risk-adjusted return.” Ultimately it is a measure of performance per unit of risk. But how do we define risk? Modern finance has provided many ways to measure it: volatility, standard deviation, beta, drawdown, value-at-risk, etc. All of these risk metrics are attempts to reduce the risk equation to a single number, all use some form of historical performance or scenarios based on historical performance, and all of these measures are by definition assumed to be temporary—tolerating some level of risk to ultimately achieve some level of return.

The problem is that such quantifications overlook a more fundamental, intuitive definition of risk: what Warren Buffett refers to as “the permanent loss of capital.” Using this definition of risk, any temporary volatility, drawdown, etc., in the past isn’t a concern. Instead, we are concerned with the potential for permanent losses moving forward. But since the future is unknown, how can we estimate the risk of a trading strategy by this definition?

The answer is that we can define strategy risk as the amount of capital that would be lost before the decision is made that the strategy is not working and to stop trading it. Every strategy, active or passive, has an implied growth rate based on history—the return side of the equation. In order to achieve a certain return, followers of the strategy must be willing to tolerate (pay) a certain level of temporary risk. The strategy risk can then be quantified in terms of how large temporary losses become before the strategy is abandoned because it’s assumed to be no longer functioning as expected. In practice, this is done using sophisticated statistical approaches, but a simple example will suffice to illustrate the point.

Let’s take another look at a passive investment in equities through this lens. Looking back 20 years, the total return of the S&P 500 has been 9.22% through the end of 2013. Over the same time period, we can also note that the maximum drawdown over this period was 53%. So the strategy risk for a passive investment in the S&P 500 must be at least as large as 53%. We have to assume that the strategy is still working if another drawdown of that magnitude is seen in the future.

But is this reasonable? Many investors may not be able to handle a 53%—hopefully, temporary—loss of capital, even if they may be ultimately happy with the realized return. The cost of potentially losing more than half of one’s capital is a steep price to pay. Yet this is the size of the loss that must be taken before an investor can consider the passive strategy to be no longer functioning as expected.

Adding active strategies can lower portfolio risk to a tolerable level.

For a stylized example, let’s say an investor can tolerate a 30% drawdown before pulling the plug on the strategy. Well, if this is the case, then the passive equities strategy is not a good match. We already know the strategy risk is larger than that. If the investor ignores this and attempts to follow the passive equities strategy hoping for the best, the results can be disastrous. Pulling the plug after a 30% drawdown converts temporary losses into permanent ones. In other words, the risk is realized and the return is not.

So what can be done? Traditional, passive approaches reduce the allocation to a market portfolio and increase the allocation to risk-free assets. The result may or may not fit the risk-reward needs of investors. Another option is to diversify all or part of the portfolio into actively managed strategies.

The business press often is unaware of the fact that many active management strategies are designed to have lower levels of strategy risk than passive strategies—as the media often focuses exclusively on performance versus an arbitrary benchmark. Adding active strategies can lower the overall portfolio risk to a level tolerable to the investor and, in doing so, also give one a fighting chance to realize the return side of the equation.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Proactive Advisor Magazine. These opinions are presented for educational purposes only.

Dave Walton, MBA, was a co-founder and partner at StatisTrade LLC, a trading strategy evaluation firm that worked with fund managers and family offices to evaluate and improve trading system performance using advanced statistical techniques. Mr. Walton won the National Association of Active Investment Managers (NAAIM) 2014 Wagner Award for one of his innovative system validation methods.

Dave Walton, MBA, was a co-founder and partner at StatisTrade LLC, a trading strategy evaluation firm that worked with fund managers and family offices to evaluate and improve trading system performance using advanced statistical techniques. Mr. Walton won the National Association of Active Investment Managers (NAAIM) 2014 Wagner Award for one of his innovative system validation methods.