Predicting how people and markets will behave is more complicated than we think

Predicting how people and markets will behave is more complicated than we think

Too often predictions are based on narrow, naive assumptions about human behavior. One of the most inaccurate is that people always make purely rational choices in attempting to maximize utility.

Trying to predict how people and markets will behave? Better understand their reference points.

In a recent attempt to address an economy plagued by moribund growth, high inflation, rising interest rates, and soaring energy prices, former U.K. Prime Minister Liz Truss tried to borrow a few pages from the Reaganomics playbook to implement a broad program of tax cuts combined with increased government spending. The context behind these actions was an attempt to institute a long-term growth plan while at the same time addressing the short-term dangers of a cold winter with unaffordable heating prices brought on by the war in Ukraine.

The originators reasoned that such a policy would warm the soul of the island nation. Instead, it led to an economic upheaval that caused the British bond market to seize up, the central bank to implement emergency measures, and a newly elected prime minister to resign after the shortest tenure in British history.

Apparently, the country was more concerned with the dangers of an out-of-control deficit and a cascading currency than the prospect of a cold winter. How could such a gross miscalculation occur?

Economists, corporate execs, market gurus, and politicians are famous for trying to boil things down to simple “if we do this, then people will do that” scenarios. Simplicity of statement, however, belies enormous complexities in how people reason that are frequently misunderstood or misinterpreted.

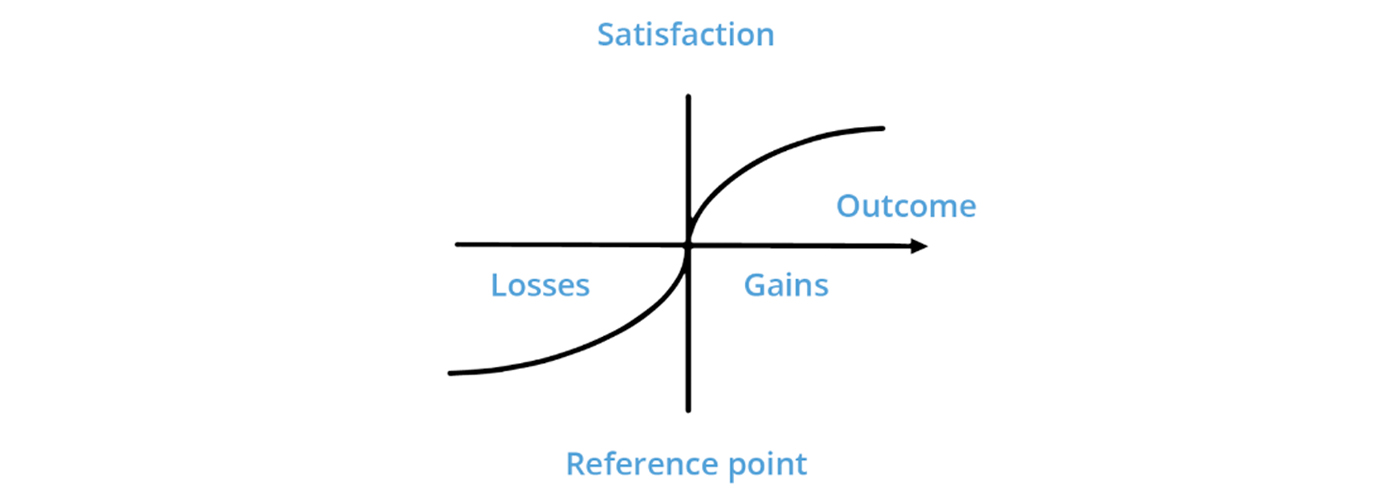

A core aspect of prospect theory

In their seminal paper on decision theory in 1979, “Prospect Theory: An Analysis of Decision under Risk,” psychologists Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky pointed prominently to the notion of reference points as one of the prime determinants of human decisions. These reference points were then shown to contribute to a number of pervasive behavioral biases, such as loss aversion, mental accounting, framing, anchoring, and representativeness.

Prior to prospect theory, our behavior as consumers and investors was succinctly described by rational utility theory—a strikingly rigid set of parameters that originated in a 1944 paper called “The Theory of Games and Economic Behavior” by John Von Neumann and Oskar Morganstern. While quite useful for analyzing games played by a handful of players, each trying to win, rational choice was arguably stretched far outside its limits when applied to financial markets with millions of players and almost as many different motivations.

Prospect theory posited for the first time that the utility function behind our decisions not only differs between gains and losses but that people make decisions based on the potential value of gains and losses and that this potential is measured from the individual’s reference point, which, of course, varies. The impact of establishing reference points as a component of decision-making is profound. It essentially says that we make our decisions based on our own reference points, which flies in the face of economic theories that more or less assume consumers will act as a homogenous group when faced with the same circumstances.

FIGURE 1: CONCEPTUAL MODEL OF PROSPECT THEORY

Source: Neuroprofiler

While rational choice works reasonably well in aggregate, it plainly fails to capture the highly nuanced and dynamic way in which individual people make decisions about finance and investing. A more intuitive approach can be found in Herbert Simon’s concept of “bounded rationality,” which acknowledges that we don’t have perfect knowledge and that our decision-making activities are largely defined by a process he called “satisficing”—the art of making quick decisions with knowingly imperfect information, but with the understanding that its “good enough” for most purposes. Unfortunately, Simon’s work does not lend itself to a usable mathematical formula for predicting market behavior, despite how much truth there is in it.

The same holds somewhat for prospect theory, which provided enormous insight and earned Kahneman a Nobel, but was also unable to provide a usable formula for predicting behavior. So, alas, we suffer the ills of rational choice, a substantially flawed but easy-to-use expression of human decision-making, and call it a day, claiming more than a few notable victims along the way, like the former British Prime Minister.

Let’s face it. Economists, financial advisors, investment managers, and politicians need something simple and direct to guide the public, even at the risk of oversimplification. We can’t very well have a functioning society or economy guided by leaders who can’t be specific because their decision models are too complex. But the truth about our behavior is that while generally driven by the motive to maximize utility, it is riddled with exceptions, nuances, different reference points, and complex feedback mechanisms. In that environment, simple overriding assumptions about our behavior can sometimes be dead wrong.

We need not look very far to find reference points everywhere in our daily actions. The fact that something is “on sale” actually has the power to change our reference points and in doing so affect the decision parameters for deciding whether to purchase things. Instead of evaluating our need for an item versus its price, as classic economics predicts, a sale can make us change our focus to the size of the perceived discount and assign more weight to that than our need for the item itself. We often laugh at ourselves for falling victim to this reference trap, but it is not uncommon for a discount to be significant enough to coax us into buying something we really didn’t need in the first place.

An example of this was demonstrated by Duke psychology professor Dan Ariely using an actual advertisement for the Economist magazine. The magazine offered people a choice of three subscriptions:

Web only: $59

Print only: $125

Web and print: $125

Ariely presented this choice to 100 of his students, yielding the following result:

Web only: 14 students

Print only: 0 students

Web and print: 86 students

Noting that the print-only option was not selected by anyone, Ariely then removed that option and polled a second set of 100 students. Those results were:

Web only: 68 students

Web and print: 32 students

The results illustrate how the reference point can completely flip a consumer’s choice between two options. A clear majority of the second group felt the additional money to add the print edition wasn’t justified. But when reframed as a choice of three, the context of the decision changed for the first group to the greater perceived bargain. The third option merely serves as a decoy that alters our reference point for the choice.

We take for granted that the retail industry twists our thinking process in this way, and we accept it as a standard marketing practice. But the effect of establishing reference points is deeply embedded in our psyche and shows up in myriad ways beyond the bargain rack. Major decisions in saving, investing, home buying, and job searching are not immune.

Reference points and stocks

Stocks are a unique phenomenon in this regard, and their movements are far more convoluted than people think. As an asset rather than a commodity, stocks are accumulated rather than consumed, which tosses a traditional supply-demand curve out the window and installs a new one that defies visual representation, due in part to complexity but also because it’s a moving target. Rising prices can actually generate increased demand but not by all constituents and only up to a point. Prices that rise fast can even lead to panic buying due to FOMO (“fear of missing out”) and short covering. But dramatic rises also tend to attract contrarians and profit takers, who bring on price corrections.

The number of players with different buy and sell reference points is boundless. And with stocks, the players in the game are not the same at any given time. One day, a stock has a predominantly institutional following, and the next day it’s on Reddit, with a completely different set of players in charge. Imagine sitting at a poker table with five other people and after every hand five new players substitute in. This is happening with stocks on a continuous basis.

We each have our reference points for stocks, interest rates, and other economic variables. We get them from personal experience, education, and conversations, but also largely from what we see and read in the media, which now overwhelms us with misleading, misinformed, and misguided content supplied by sources either trying to sell us something, further their own aims, or rally us to their way of thinking. Like it or not, outside sources are planting untold numbers of reference points into our subconscious, which our brains happily soak up like a sponge and store, without judgment, to help facilitate future decisions.

Reference points are also slippery and can vary with time and circumstance. People who were looking to purchase a home when mortgages could be had for 3% are balking in big numbers at now having to pay 7%. But if rates continued up to say 8% or 9% by January and then dropped back to 7% by spring, how many of these people will then shift their reference to 9% and conclude that 7% looks like a good deal?

Stock market reference points are also notoriously fluid. Many investors frequently flip from buyers to sellers in a single day, depending on the indicators they watch, the price action of the herd, or comments they glean from the media. Long-termers attribute this to “noise trading,” but that may just be a convenient dismissal for what they see as unpredictable short-term movements. Meanwhile, the long term is merely the sum of all short-term movements, and the long-termers have their reference points for decisions as well.

As investors, we tend to build into our decision-making our personal reference points of loss, gain, and breakeven. For example, think about the key level for the S&P 500 of around 1,500. For investors who built the bulk of their investment wealth in the 1980s and 1990s, this was a significant and welcome milestone in 2000. Following both the massive drawdowns of 2001–2002 and 2008–2009, it represented a key breakeven point as markets later recovered from bear markets. For investors today, it would represent an unthinkable additional market decline of over 50% (unlikely, though not outside the realm of possibility).

FIGURE 2: 30-YEAR HISTORICAL VIEW OF THE S&P 500 INDEX

Note: Shaded areas are recessions. Data as of Dec. 5, 2022.

Source: MacroTrends

Reference points are powerful subconscious decision influencers. They are so important to our decision process that in cases where we have no viable reference point, we have difficulty making a judgment or decision at all. I demonstrate this in my behavioral finance class by asking the students to give me an estimate of the number of worldwide employees at Walmart. Most just stare back at me blankly, unable to come up with anything they feel comfortable using as a viable reference point.

Moving targets

Besides being unique and complex, reference points are also dynamic, changing almost on a continual basis in active markets through feedback mechanisms. Robert Shiller addressed this topic in “Irrational Exuberance,” telling us that “feedback loop dynamics can generate complex and even apparently random behavior … and even some quite simple feedback loops have been demonstrated to yield behavior that looks so complicated as to suggest randomness. If we suppose that there are many kinds of feedback loops operating in the economy and many kinds of precipitating factors, then we may conclude that the apparent randomness of the stock market … might not be so inexplicable at all.”

Every major market move is different in nature, timing, and prevailing sentiment. As a result, reference points are not the same either. Young investors will look back at the spring of 2020 when the market completed a brief correction and then nearly doubled by the end of 2022. Older investors may have as their reference the 2008 decline into March of 2009, while still older investors have as their reference the 2000 decline—or even the crash of 1987. We know the circumstances of these declines were starkly different, but that doesn’t change the fact that we carry these reference points with us when we make decisions based on them in the future.

The latest thinking, espoused by Andrew Lo in his book “Adaptive Markets,” takes the concept of market dynamics even further by suggesting that markets change over time due to processes not unlike those in evolutionary biology. In Dr. Lo’s scenario, markets actually evolve through processes like adaptation and natural selection, which change their very nature. One can only imagine how that would impact everyone’s reference points.

Trying to second-guess what the public’s overall reference points are and translate that into expected market behavior is therefore a hopeless exercise, and relying on that to make trading decisions is accordingly dangerous. We can, however, become more mindful of what our own reference points are and take steps to ensure they are relevant and sound.

We do that by conducting valid, objective research or by consulting other third-party sources who do. It also argues for the merits of rules-based investment strategies, which can adapt to the realities of changing market/price conditions and can eliminate emotion and irrelevant or unrealistic reference points from the investment decision-making process.

The important thing is to recognize how integral reference points are to our decision process and to check them now and then to make sure they are anchored in reality. Financial advisors can play a valuable role in not only clarifying the risk profile and risk capacity of their clients but also in understanding each client’s specific “reference points” when it comes to their overall financial picture and their investment goals.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Proactive Advisor Magazine. These opinions are presented for educational purposes only.

New this week:

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.