New Year’s resolutions—or setting achievable goals?

New Year’s resolutions—or setting achievable goals?

Financial advisors can more effectively help clients meet their investment objectives if they incorporate risk-managed, goals-based strategies—as well as behavioral finance techniques—to minimize behaviors that can derail an investment plan.

They say New Year’s resolutions are meant to be broken.

There is a good chance that at least a few readers of this article are already frustrated—just four weeks into the year—by their inability to follow through on some of their well-intentioned resolutions.

In fact, it is probably more than a few.

According to research from global firm YouGov, 34% of American adults planned to make New Year’s resolutions or set a goal for 2024.

But YouGov research also indicated that by February of the previous year, just 22% of U.S. adults say that they stuck to all of their 2023 resolutions, and 54% said that they were able to stick to some of their resolutions, though not all of them.

That is a somewhat more optimistic outlook than the research findings published at Gallup.com, which says, “By mid-February, 80% of the people who set New Year’s resolutions will have abandoned them—no matter how large or small the goal.”

Good luck to you if you are still working on a 2024 resolution—though luck really has nothing to do with it!

Resolutions vs. goal setting

It was initially surprising to see the estimate that only 34% of American adults make New Year’s resolutions. It felt low.

But then I had some conversations with several colleagues and, if they are representative at all, it now feels high.

They collectively had an interesting insight. They expressed that making New Year’s resolutions feels a little contrived or gimmicky—almost guaranteeing some level of “failure.” None usually make any specific resolutions at the end of the calendar year.

However, they almost all universally “set goals” every year. They feel that it makes much more sense to establish a series of realistic and achievable milestones, or steps, in getting to a larger goal—rather than the “all or nothing” contextual feeling of a “resolution.”

The opinions of this group varied widely, but in many ways they closely mirrored some of the comments found in an Atlantic Monthly article on resolutions:

“Psychologists, businesspeople, and motivational coaches offer endless, sometimes conflicting, advice: Set bite-size goals that you can realistically accomplish; set difficult goals that stimulate you with a challenge; make your goals easy to measure; seek meaningful well-being rather than shallow self-improvement; avoid temptation; visualize success; congratulate yourself for progress; don’t give up if you’re lagging. …”

But the author also points out, “If goals are too narrow or too challenging or too many are attempted at once, they can obscure the bigger picture or lead people to focus disproportionately on short-term gains. Getting goals just right is hard.”

Goals-based investing

In the dozens of interviews we have conducted with successful financial advisors across the U.S., the vast majority employ some version of goals-based financial and investment planning.

For these advisors, goals-based investing has two meanings in today’s retirement-planning environment:

- The practical notion that an investment plan should be based on achieving realistic goals customized to an individual’s (or couple’s) overall financial-planning requirements, risk profile, and time horizon—not some far less relevant market benchmark. It starts with a financial plan that attempts to identify realistic levels of returns that will help a client meet their financial goals, typically beginning with the fundamental goal of helping to provide adequate income in retirement.

- The philosophical idea that investment success should be measured on how it helps clients achieve the lifestyle goals they desire. Those goals could be the most basic, such as attaining a comfortable retirement. Or, they could also be more ambitious, such as helping fund a grandchild’s college education, buying that long-desired vacation home or condo, making a significant contribution to a favored charity, or going back to school to jump-start a new career.

Why choose goals-based, risk-managed investing over traditional passive asset allocation?

For decades, investment and financial advisors have applied the principles of modern portfolio theory (MPT), the capital asset pricing model (CAPM), and the efficient frontier theory when constructing client portfolios. These principles were largely based on the work of American economist Harry Markowitz, who wrote an article titled “Portfolio Selection” in 1952, published in the Journal of Finance. That paper laid out the mathematical arguments in favor of portfolio diversification. Markowitz later shared the Nobel Prize in Economics in 1990 with two other scholars “for their pioneering work in the theory of financial economics.”

MPT theory retains strong advocates, and it generally served investors well during the last few decades of the 20th century. Says Investopedia, “Modern portfolio theory has had a marked impact on how investors perceive risk, return, and portfolio management. The theory demonstrates that portfolio diversification can reduce investment risk.”

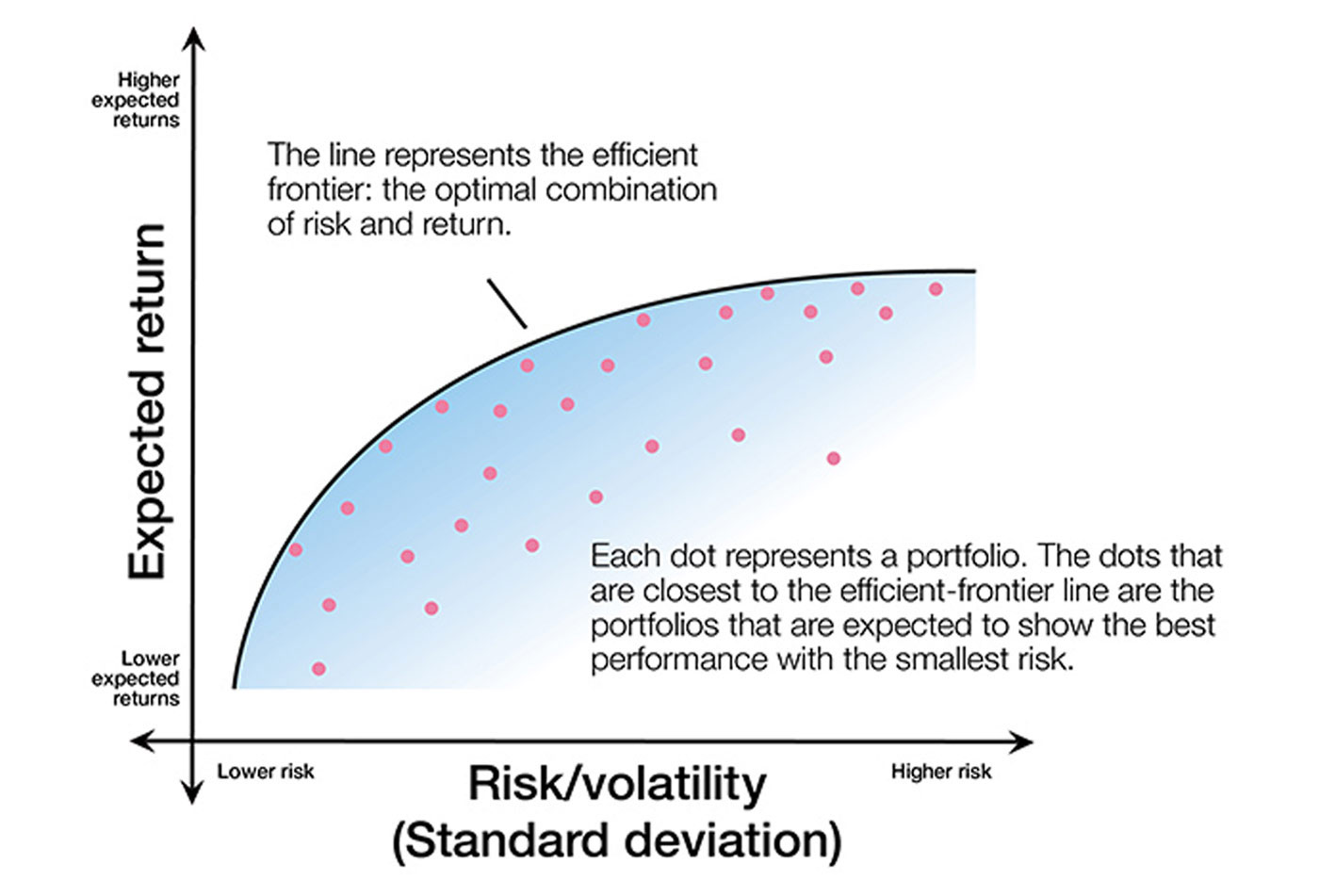

There is little doubt that focusing on the relationship of risk and return was, and is, a compelling and positive tool for investors and their advisors as they consider investment options. Efficient frontier theory took this to a new conceptual level, identifying “the portfolio composition(s) that provide one with the maximum return for a given degree of risk (or alternatively, the least amount of risk for a given return).”

On a theoretical level, this sounds vastly superior to selecting investment vehicles and portfolio composition with little regard to risk. And it is. MPT and efficient frontier theory still have valuable roles to play in examining portfolio alternatives.

THEORETICAL VIEW OF THE EFFICIENT FRONTIER CURVE

Note: This graph is an example of what the efficient frontier equation looks like when plotted. The purpose of the frontier is to maximize returns while minimizing volatility.

Source: smart401k.com

But the broad and deep market downturns of the 21st century exposed some serious weaknesses in the theory of classic asset-allocation strategies and MPT, especially as they relied on a passive approach to investing. Advisors and their clients witnessed several “real-world” effects on markets and investor behavior in times of severe stress, such as that seen during the dot-com meltdown of the early 2000s and the credit crisis of 2008–2009:

- MPT/efficient frontier theory was severely challenged by traditional asset-class correlations not behaving as expected, which was explored in Proactive Advisor Magazine’s article, “A more efficient (and profitable) frontier.” That article examined one of the key underpinnings of efficient frontier theory, concluding, “The efficient frontier was wildly different for every 10-year period from 1950 to 2009 (and this inconsistency persisted from 2010 to 2014). What that means is using any period of historical asset-class returns to create an optimal portfolio for the following 10 or 20 years is, at best, unreliable.”

- The sequence-of-returns “dilemma” undermines even very capable application of MPT for client accounts. As numerous studies have shown, when clients are in the distribution phase of retirement, the sequencing of their investment returns can have disastrous effects on the long-term viability of generating an income stream. Put simply, two portfolios may have the exact same “average return” over a 20- or 30-year period, but the timing of those returns can mean the difference between building a very comfortable retirement trajectory and simply running out of money.

- Classic passive asset allocation according to MPT, while perhaps “maximizing” return relative to risk, does not mean risk is totally mitigated. As one experienced financial advisor told Proactive Advisor Magazine, “I was a firm believer in modern portfolio theory up until the financial crisis of 2008–09. I always thought it was sufficient to have client portfolios that were optimized as much as possible for risk and return. However, while a portfolio might beat the worst of the market’s performance in a severe crash, it is still unacceptable to see portfolio declines of over 20% or 30%.”

- To the point above, the most troubling aspects of client behavior can surface when markets crash—despite having “well-constructed” portfolios. The herding mentality can come to the forefront when investors perceive “the investment world is coming to an end,” and emotional panic dominates decision-making. In their 2015 book “Applied Asset and Risk Management,” authors Marcus Schulmerich, Yves-Michel Leporcher, and Ching-Hwa Eu had this to say in their chapter “Modern Portfolio Theory and Its Problems”: “Moreover, traditional finance theory cannot explain market situations like crashes and stock market anomalies. … The global financial crisis caused many to reexamine practices in the finance industry and to wonder if there had been too strict an adherence to theoretical concepts at the expense of a more pragmatic or practical viewpoint.”

Applying the objectives of goals-based investing

It is perhaps easiest to start with what goals-based investing is not. It is not an investment plan that seeks to duplicate broad market results or build comparisons to popular market benchmarks.

It starts with a financial plan that attempts to identify realistic levels of returns that will help a client meet their financial goals, usually prioritizing the core objective of producing income (along with other sources) for retirement.

By its very nature, a goals-based investment plan will not see returns anywhere near those of the best bull markets. But, importantly, it should also not suffer the worst drawdowns seen in severe bear markets. In general, the objectives of a goals-based investment plan are to smooth out volatility, achieve steadier returns, and project a range of returns for a client that is consistent with their risk profile and has a reasonably strong mathematical probability for success over time.

By incorporating goals-based strategies, financial advisors can better tailor investment approaches to meet clients’ specific needs and desires. Combined with the behavioral finance benefits of this process, clients are more likely to have realistic and achievable expectations, enabling them to stay the course to meet—or even exceed—their stated goals.

Many financial advisors have not needed a deep and well-researched academic analysis to come to these very same conclusions, looking for new solutions for clients’ long-term investment plans. Many of these advisors have turned to a combination of “goals-based investing” and outsourced investment management, working with investment managers who provide more active and risk-mitigating strategies.

***

Ashvin Chhabra, former chief investment officer at Merrill Lynch Wealth Management and author of the book, “The Aspirational Investor: Taming the Markets to Achieve Your Life’s Goals” said it well in a CNBC interview. In discussing aspirational goals, he noted, “At the end of your life, saying ‘I beat the S&P by 3 percent’ doesn’t mean anything. But if you say, ‘I invested well, I had a nice house, my kids went to a good school,’ that’s something.”

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and the sources cited and do not necessarily represent the views of Proactive Advisor Magazine. This material is presented for educational purposes only.

This article first published in Proactive Advisor Magazine on Feb. 16, 2022, Volume 33, Issue 7. Some information and sources have been updated.

New this week:

David Wismer is editor of Proactive Advisor Magazine. Mr. Wismer has deep experience in the communications field and content/editorial development. He has worked across many financial-services categories, including asset management, banking, insurance, financial media, exchange-traded products, and wealth management.

David Wismer is editor of Proactive Advisor Magazine. Mr. Wismer has deep experience in the communications field and content/editorial development. He has worked across many financial-services categories, including asset management, banking, insurance, financial media, exchange-traded products, and wealth management.