Factor investing: Investment management’s latest fad or important evolution?

Factor investing: Investment management’s latest fad or important evolution?

It would be easy to dismiss factor investing as a convenient reason for ETF issuers to introduce an endless assortment of new products or the latest marketing gimmick in the world of passive investing. A deeper look says it is much more—and as much a benefit to active managers as passive investors.

Estimates say there are over a thousand factor-related ETFs now and more than a trillion dollars of assets in them. This does not consider how much factor investing exists in public mutual funds or in institutional portfolios and hedge funds.

Suffice it to say that factor-based strategies are now quite well-entrenched in the broad spectrum of professional money management. But the mere popularity of an investment theme or approach doesn’t necessarily speak to its underlying impact.

One could still interpret the factor craze as just another incarnation of an industry obsessed with performance and intent on finding even the tiniest competitive advantage. Also, it would be easy to dismiss factor investing as just another fad surfing on top of the giant passive investing wave.

Andrew Ang, head of factor investing strategies at Blackrock, would strongly disagree with both thoughts.

In a recent Bloomberg interview with Barry Ritholtz (supported by articles Ang has posted on the Blackrock website), Ang stated he believes factors are what drives returns in equity investing (as well as other asset classes) and that it has already evolved far past the initial three-factor model produced by Eugene Fama and Kenneth French back in the 1990s. He sees factors as being broad, persistent drivers of returns. We will discuss more about Ang’s approach to factors later.

Bill Sharpe’s capital asset pricing model (CAPM) contained only beta and the risk-free interest rate, making it essentially a single-factor pricing model, with beta serving as the stand-in proxy for risk. In an efficient market, risk may well be the primary driver of long-term return, but many found CAPM to be too simplistic.

Fama and French initially added two more factors to CAPM: small caps (size) and low book-to-market (value), thus creating the well-known Fama-French three-factor model. Later in 2014, they added profitability and capital investment, making it a five-factor model. Others came up with factors for momentum, quality, low volatility, and dividend yield.

The most commonly accepted definition of the five major “style factors” today are value, quality, size, momentum, and minimum volatility. These fundamental factors can theoretically help explain risk and return within a variety of asset classes.

Some researchers claim that you can come up with hundreds of factors. (However, take this with a grain of salt. With enough computing time and analysis, you might also come up with a hundred reasons why even the worst football team in the league should win the Super Bowl.)

It is self-evident that the primary factors previously mentioned are really nothing more than characteristics of stocks that were part of fundamental securities analysis for decades. What is new is how they are being used. Now they form the basis of a new way to classify stocks (or other asset classes), creating a series of asset subclasses based on these characteristics. Cross-sectioning stocks in this manner turned up valuation inefficiencies that were otherwise hidden. Factor focus also allows these characteristics to be exquisitely fine-tuned across the universe of available stocks and then tracked in minute detail over time.

For example, identifying small caps used to be a fairly crude distinction based on market capitalization, which of course changes continuously with market price. Reclassifying a stock based on its market cap might have previously occurred once per quarter or perhaps even annually, and the allocation to small caps was viewed pretty much from an overall perspective on beta. With today’s computing power, a factor such as size can now be defined by an array of size-related characteristics and updated as often as data becomes available. More importantly, the factor can be fine-tuned and tracked in such a way as to determine exactly how inefficiently the market prices it and then to use it to tilt portfolios to exploit that inefficiency. It can then be used to either capture alpha, enhance diversification, or reduce risk accordingly.

Here are some examples of major factors used in many of today’s analytical models.

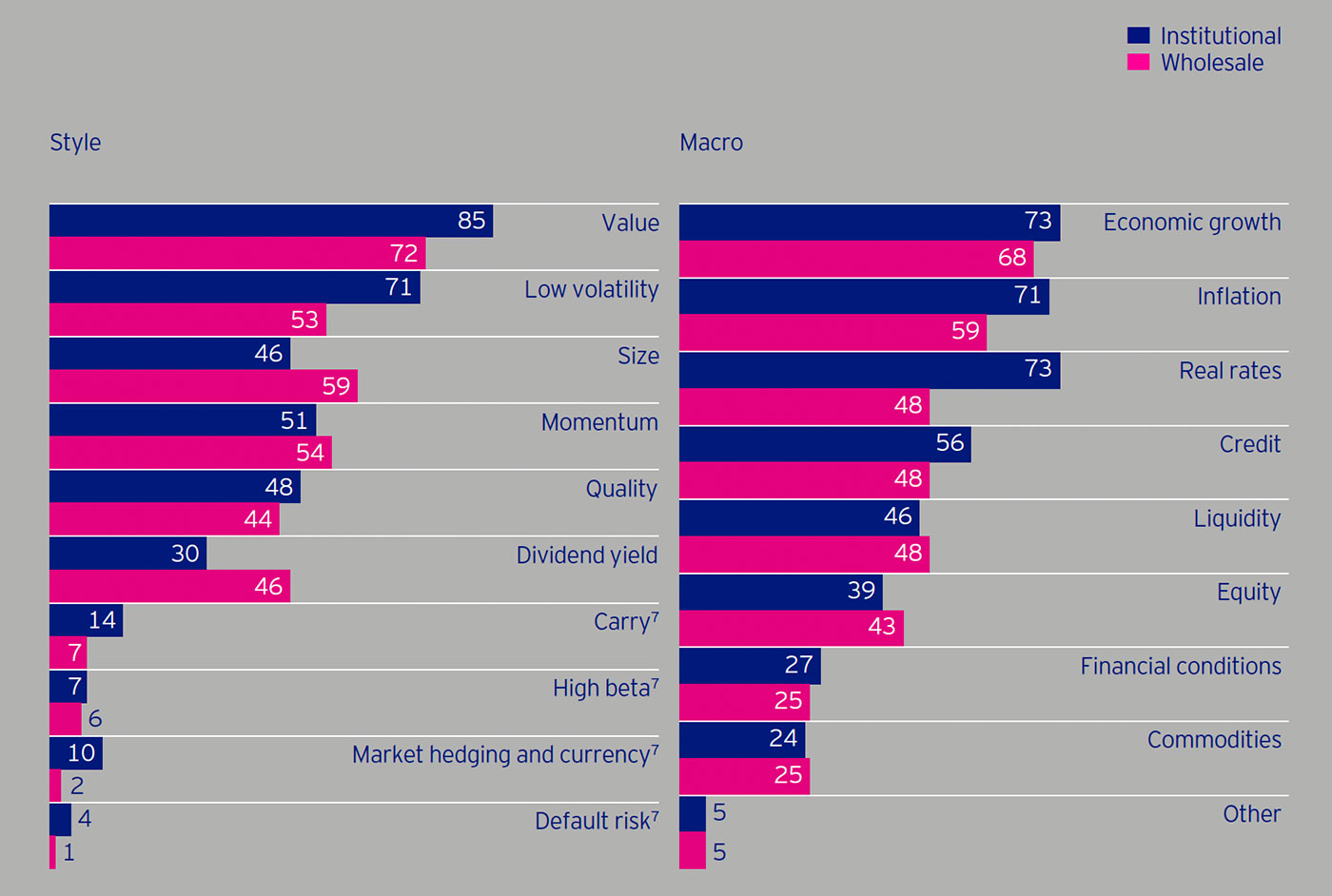

Source: Invesco Global Factor Investing Study, 2018.

The grand view of finance has evolved considerably since its virtual “big bang” in the mid-1900s. Aided by advances in data analysis and computing power, factor investing is shaping up to be a logical next step in the progression of that evolution. There are at least five reasons why this is so.

For starters, factor investing was born with an instant pedigree, as it is a direct descendant of the efficient market hypothesis (EMH) and CAPM. Having the same creators as EMH (Nobel laureate Eugene Fama along with longtime collaborator Ken French) gave factor investing an instant sense of credibility—one that has now been affirmed by substantial academic and industry research.

Second, factors have intuitive appeal, and this is not a trivial consideration. Even nonfinancial professionals understand size, value, and volatility. Comprehensive investment strategies and techniques are often developed by Ph.D.s with impressive quantitative skills and sophisticated computers, but they must first get the blessings of investment committees, boards, and administrators. These blessings are much more likely to be given to intuitive concepts than to obscure ones. This can be even more pronounced in the pension world where plan administrators often come from the ranks of the labor groups represented by that plan—for example, teachers, municipal employees, law enforcement, or trade unions.

Third, factors represent items that are already familiar rather than radical new concepts, which reduces the impact of conservative bias (skepticism of new ideas). Most of the factors represent characteristics of companies identified a century ago as key variables in the value equation and were already present in the collective mindset. Small caps were already treated as a separate asset class (or at least a subclass), and most investors know what smaller companies represent in terms of higher risk and volatility. Treating small-cap stocks as a factor allows managers to fine-tune just what aspect of size they want to use and to either meld or separate the size factor from, say, the volatility factor, which might encompass many of the same stocks.

Fourth, factor investing enjoys a unique position amid the debate surrounding alpha versus market efficiency, essentially providing both sides with something they can grab on to. For market efficiency purists, the factors provide an enhancement for passive strategies that seek to gain traction against a benchmark index by tilting toward a diversified set of factors that have been shown to outperform the benchmark index over a long period. For those who see the factors as evidence of inefficiency, it provides a way to exploit such inefficiency for potential gain.

Last, factors also enjoy a unique position as a tool for both active and passive investors and managers.

The passive camp employs factors as products that fit long-term diversified objectives, but without being just another index. This has a number of attractions for both ETF issuers and investors. For investors, it removes the awkward responsibility of trying to figure out how to allocate across indexes for optimal long-term diversification. It also reduces the temptation of a passive investor to make subjective decisions about what combination of indexes to invest in during different circumstances or market cycles. These attractions would be beneficial to advisors using passive funds as well. Now, a passive approach can be simplified into a single multi-factor fund that will serve both as an all-weather solution and as one that is less likely to be perceived as needing to be changed over time.

Furthermore, factor investing facilitates hybrid active-passive strategies as well. It allows funds with specified factors to be added to portfolios to achieve a specific objective for either risk or diversification. It also allows the mix to be modified over time.

Active managers, on the other hand, have an entire set of factor-based tools for designing and managing portfolios. Factor criteria provide a more nuanced way to manage active portfolios, and factors can be used at the portfolio level or within specific asset classes. This enables managers to focus directly on characteristics such as value or volatility rather than on asset classes or sectors that only represent a proxy for those characteristics, while at the same time incorporating a hodgepodge of other undesired characteristics. In addition, individual factors can be used to customize specific portfolios where that characteristic is needed or desired to meet portfolio objectives.

Active managers, on the other hand, have an entire set of factor-based tools for designing and managing portfolios. Factor criteria provide a more nuanced way to manage active portfolios, and factors can be used at the portfolio level or within specific asset classes. This enables managers to focus directly on characteristics such as value or volatility rather than on asset classes or sectors that only represent a proxy for those characteristics, while at the same time incorporating a hodgepodge of other undesired characteristics. In addition, individual factors can be used to customize specific portfolios where that characteristic is needed or desired to meet portfolio objectives.

Based on Ang’s approach at Blackrock, there is much more that factors can do for active management. Even when factor performance is statistically valid over a long period, random variations occur in the short run—as do not-so-random variations due to external influences such as the business cycle, investor biases, and what Ang calls “structural factors,” such as the propensity of pension funds to reach for higher risk in a low-interest-rate environment to meet their liabilities. For example, factors such as size, quality, dividends, and value can be expected to perform better during certain parts of the business cycle than others. This opens the door to factor timing, though Ang prefers the term “factor tilting” to avoid the negative connotations of “market timing.”

Ang sees the factor evolution riding a wave of passive investing, a never-ending search for alpha, advances in quant and tech investing, and increased focus on risk management. He acknowledges that asset allocation is the primary determinant of portfolio performance and first looks at what drives asset-class returns. He concludes that the “big three”—economic growth, real interest rates, and inflation—explain 85% of the returns across asset classes. To these he adds credit, emerging markets, and liquidity. He then looks at what he calls the “style” factors (value, momentum, quality, size, and volatility) within each asset class. This takes his factor approach beyond just equities into bonds, commodities, real estate, and private equity.

For the next frontier of factor investing, Ang points out that the factors themselves display characteristics that can, and should, be tracked. He readily admits that long-term factor investors must be prepared for drawdowns versus their benchmark indexes and views such drawdowns as potential opportunities. (He cites the 2018–2019 underperformance of value stocks to be the fourth worst ever.) He notes that Blackrock studies valuation measures (a factor’s richness or cheapness compared to its own history), relative strength (whether a factor has a supportive performance trend), and dispersion (how robust the opportunity set is for a factor).

Blackrock also studies the relative strength of specific factors by analyzing their second derivatives, such as the momentum of momentum or the volatility of volatility. Ang says that volatility, for example, does not have a continuous relationship with return. Increased volatility leads to higher long-term returns in general, but then above a certain point, the relationship abruptly turns negative. He says Blackrock is now also examining the application of factors inside sectors or to specific international markets and is aggregating factors to address specific objectives. Of course, all of this analysis needs to be considered in the context of scalability, turnover, and cost.

Some people see the sheer popularity of factor investing as a reason to speculate that followers now constitute a crowded room where the weight of assets allocated to factors dilutes or potentially negates the potential long-term advantages they may hold. If the factors are just pockets of exploitable inefficiency created by behavioral biases, then overcrowding may indeed be a possibility. If, on the other hand, the factors represent persistent long-term value due to other external influences, then, as Ang believes, there will be value in factor investing for decades to come.

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.