ESG investing reflects highly personal client goals—advisors need to treat it that way

ESG investing reflects highly personal client goals—advisors need to treat it that way

Success with ESG/SRI-focused clients will likely depend more on choice architecture, framing, and mental-accounting skills than on complex portfolio-construction techniques.

Melding a client’s investment strategies with their personal goals is part of every advisor’s role. Setting up a philanthropic trust? Making a major purchase? Getting married or divorced? No problem. But catering to a client’s feelings about corporate ethics, gender diversity, or carbon footprints is a different type of challenge entirely.

Social “expression” with one’s investments has become a popular personal goal—one that is highly subjective, differs greatly among clients, and in many cases needs to be integrated directly into a client’s basic investment strategy. It’s no longer sufficient to just construct a diversified portfolio of stocks deemed to have risk-reward characteristics suitable to the client.

Many clients now want to know how those rewards are being generated and at what cost to society. They want companies they own to be ethical and upstanding corporate citizens, and they want products and services produced by them to provide sustainable benefit to customers, employees, and society as a whole. Oh, and they haven’t forgotten about performance.

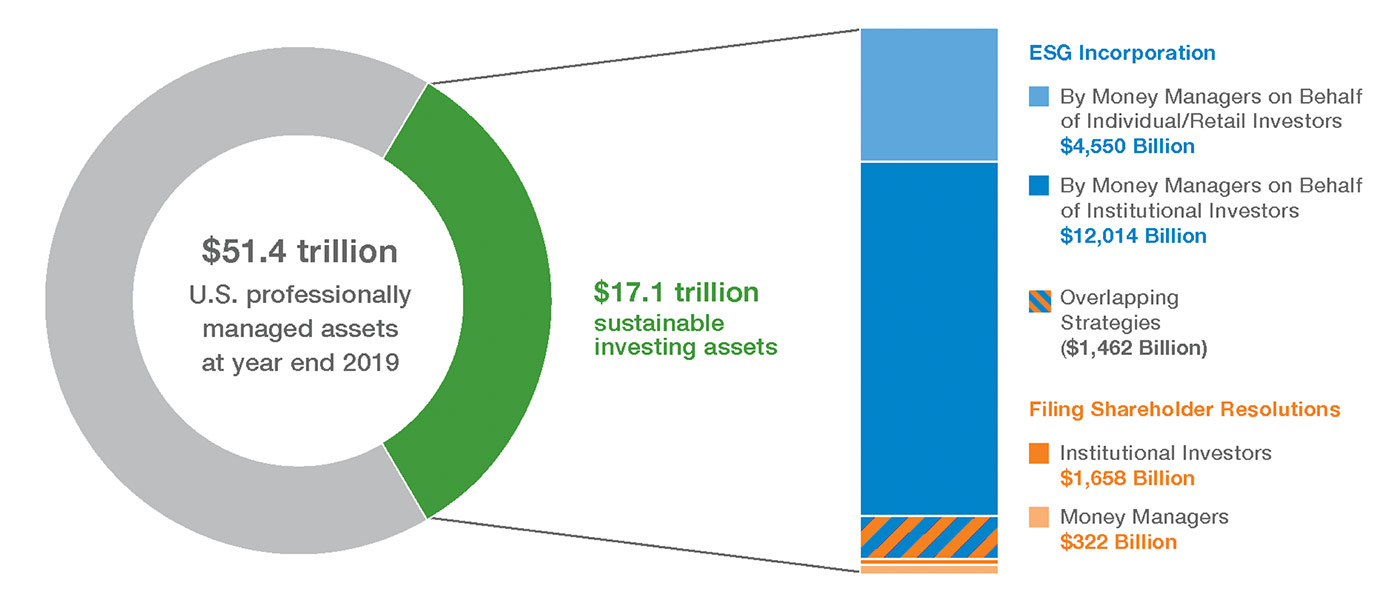

The phenomenon that is alternately referred to as SRI (socially responsible investing), impact investing, sustainable investing, or ESG (environmental, social, and governance) investing is not a flash in the pan. It’s been around for more than 30 years and has now gained significant momentum. It is well entrenched in both institutional and retail investing, and it is present worldwide. As advisors move more deeply into goals-based investing for their clients, they will not only encounter these goals more often, but they are also actually helping to fuel the movement. The Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investment (US SIF Foundation) estimates that as much as one-third of professionally managed U.S. investment assets now incorporate sustainability into their objectives.

Source: The Forum for Sustainable and Responsible Investment (US SIF Foundation)

One of the key questions is this: Can financial advisors rely on their current skills and toolkits to satisfy client concerns about corporate social responsibility while adhering to the responsible analysis of risk, return, and fiduciary considerations for the client’s overall investment plan?

Personal goals have generally been something an advisor could address separately from performance goals. They might require some liquidations or shifts in assets but did not necessarily foster a change to the underlying investment strategy.

Expressing SRI or ESG preferences is different. These preferences are hugely subjective, have multiple areas of concern, and can be layered directly on top of existing performance objectives. And while there are numerous analytical tools that advisors and investment managers can use to optimize and actively manage portfolios, subjective inputs can present some issues for advisors.

In some respects, it was much easier to manage social concerns in portfolios when the movement was in its infancy more than three decades ago. Back then, very little social data was available on public companies, so the expression of a client’s concern generally entailed excluding companies from their portfolios that were either egregious polluters or “sin stocks,” such as casinos, tobacco companies, or alcohol distributors.

Today, however, the situation is radically different. The presence of readily available data on public companies across numerous social criteria not only provides enormously greater insight as to the social character of our corporate citizens, but it also enables us to index companies on these criteria and subsequently rank them. Those rankings can be used alongside financial data to screen stocks for portfolio construction and management purposes. This represents what may be considered the “financification” of ESG data—the melding of financial and nonfinancial data to determine the overall attractiveness of a stock.

Having all of this new social data, however, is both a blessing and a curse. Data accuracy aside (much of it is still unaudited and provided voluntarily), having the data opens a revealing window to criteria that were otherwise hidden from public view in most companies. That visibility alone is now increasing the self-consciousness of companies that rank low compared with competitors, causing them to take steps toward improving their social profile.

The flip side is that having so much data can overwhelm and complicate the investment management process. A data-driven strategy is likely to work well at the institutional level when you have large, sophisticated clients who are already comfortable with a more analytical approach to their portfolios and who are looking to add a broad expression of social consciousness through a socially responsible screen or tilt. But at the retail level, investors can be much more focused on specific aspects of social responsibility and more prone to modifying that view as circumstances change. That can lead to a convoluted process of trying to appease many clients, each with a different social expression and different priorities about how to balance that expression with risk and performance.

Consequently, knowing how thousands of companies rank on their carbon footprint, gender diversity, or executive compensation is of great value in terms of improving corporate social responsibility, but how practical is it in managing the spectrum of client portfolios? How do you even begin to get a client to tell you what level of carbon footprint they are willing to accept, how much weight it should be given, or whether you want to limit your portfolio to those below a certain level? How do you reconcile both positive and negative social criteria on target companies? And what will happen when there is a severe decline? Will the client feel that social criteria are still important, or will they want to abandon social responsibility in favor of stricter risk-management guidelines? The good news is that certain investment managers do offer robust ESG or SRI strategies that incorporate many of the same sophisticated risk-management approaches inherent in their other strategy offerings.

If you explore client perceptions and concerns regarding ESG issues, you will likely find them to fall somewhere along a lengthy continuum with regard to which social concerns they feel are important, what they know about ESG measurements and rankings, and how that data should be considered vis-a-vis performance targets.

Unless there is a clear and simple understanding about the way both social and performance goals will be handled by a single active strategy, an advisor could be faced with the untenable task of matching each client to a customized strategy for handling their specific mix of requirements.

This is where a behavioral approach comes in.

It’s a well-known fact that providing people with too much choice has negative effects. Faced with too many choices or too much data, people will automatically try to simplify. If the resulting choices and data still prove overwhelming, they will choose arbitrarily or simply avoid a decision entirely.

It is also known that how the choices are constructed makes a difference in what people choose. This has led to a science around designing choices. Having decided on a car you like, a salesperson will not ask you what color you want. Instead, they will ask, “Do you want that in white, black, or silver?”—nudging you to select a color they have in stock. Your local movie theater offers you three different drink sizes, pointing to the oversized one as the “best value.” You are being psychologically pushed into selecting the largest size because your innate desire for value tends to outweigh your sense of how thirsty you actually are or how unhealthy the drink may be. The intentional structuring of such decisions around selected, discreet choices is called “choice architecture,” and it is used way more often on us than you think.

Advisors already use choice architecture for risk profiling. They do not ask an open-ended question such as, “How much risk are you willing to take?” If they did, they would get all manner of hard-to-interpret and harder-to-implement responses. Instead, most will ask clients—or use some methodology—to classify their level of risk into one of three broad categories: conservative, moderate, or aggressive. These are oversimplified for illustration purposes, and we know that risk is far more nuanced than that, but we also know that these categories are general enough to accommodate most any investment. Investments have ranges of risk rather than discreet risk characteristics anyway. The simplification of risk into three standard categories provides enough selection for clients to understand and react to. While not very scientific, it reliably gets advisors and clients into a ballpark that both can work in.

Choice architecture has value in ESG discussions as well. Without a simplified set of choices to present to a client, ESG concerns can go off in numerous different directions and get hopelessly mired in conflicting priorities. Issues of concern can range from ethics to energy consumption, green products to gender diversity, and carbon footprint to compensation. Many companies will rank low in one area but high in others. The sheer number of different ways social factors can be classified, as well as the varying degrees of feelings clients have about them, can be overwhelming. If the choice isn’t simplified for them like it is with risk, the advisor can easily end up with a set of incongruous goals that cannot be addressed in a practical or scalable way.

Clients likely have anywhere from one to three social-conscience hot buttons. The task for advisors is cut to the chase. Asking an open-ended question such as “What are your top social concerns or objectives?” might elicit a response that isn’t practically actionable. The best approach for an advisor may be to identify perhaps three or four strategy options that address the main points of concern people have while representing goals that can be addressed systematically. The choices might include an index filter, a portfolio tilt, and a screen of inclusions and exclusions, all of which can accomplish the desired blend of performance optimization with an ESG overlay.

The task of condensing all of a client’s social concerns into an actionable short list also requires effective framing, the behavioral version of spin-doctoring, or how you will position your approach to the client. How you frame the discussion of social consciousness will determine how the client perceives it, and those perceptions then determine what expectations a client will anchor into their subconscious minds.

For example, a common theme that permeates the ESG narrative these days is the notion that social responsibility translates over time into improved financial performance as well. This theme, while supported by some research studies, also has been promulgated, in part, as marketing support developed by companies with ESG funds.

These funds need to counter the initial impressions held by many that adherence to social requirements would create a drag on portfolio performance due to the extra costs required for compliance and the elimination of some stronger-performing companies from consideration in portfolios. While the performance argument made by fund companies or investment firms may well have merit for specific ESG-focused strategies, it should not be generalized to all ESG strategies and could become a dangerous anchor with clients, who would then expect their ESG-tilted portfolios to outperform the standard benchmarks. Advisors may find a better behavioral approach when discussing the potential returns of a specific ESG investment strategy with clients is to “underpromise” and, hopefully, see the strategy “overdeliver” versus more conservative expectations.

In addition, success in ESG investing often isn’t measured in the same way as it is traditionally measured in an investment portfolio. While company performance can be measured and compared to numerous targets or a benchmark, it is far more difficult to measure the effectiveness of a company’s ESG efforts.

Depending on what a client’s ESG objectives are, many will just take for granted that their portfolio has a social conscience and focus on performance. If the ESG preference was an exclusion, inclusion, or tilt to the portfolio, the client may focus on the perceived effect those constraints had on overall performance, which might not be able to be calculated, unless there is a related non-ESG benchmark available to measure it against.

There is, however, a way for advisors to avoid the vagaries of performance altogether with some clients by using a little mental accounting.

Integrating ESG criteria directly into an existing portfolio strategy may be easier for institutions, where portfolio management is highly customized already. But trying to find an integrated solution that appeals across a broad book of retail clients can be far harder. When the integrated solution doesn’t fit the situation, financial advisors can use mental accounting techniques to separate the ESG goal from the overall performance goal.

Mental accounting is the psychological separation of money or assets into arbitrary categories (commonly referred to as “buckets”) and then valuing or treating those buckets differently. The bias is pervasive for many investors. While it can be a problem in getting clients to meet certain objectives, it can actually aid them in meeting others. It is a harmful practice when it causes someone to take out a car loan at 8% rather than pull money from a savings account earning 1%. But it can be helpful when it encourages someone to “max out” their retirement account contributions in order to get a company match. It can be helpful in achieving ESG objectives as well.

Remembering that social concerns are largely a subjective goal, there is no reason to assume that such a goal must necessarily be integrated throughout a person’s entire portfolio. That is one option, but another is to simply set up a separate bucket specifically to address the ESG aspect of a client’s objectives.

This is something advisors already do with other objectives. Advisors recommend, for example, that people maintain an emergency fund, which usually involves partitioning money into a separate account in order to keep it liquid. That means getting a lower return on that money than might otherwise be achieved if the funds were left in the larger portfolio. But advisors know that people need the psychological crutch of separating that money into a different account from their investments so that they will be less inclined to spend or take risks with it.

The same approach can be applied to ESG goals.

It is common among self-managed investors to mentally account for their social concerns through a separate bucket of money from their primary investments. It removes all the complexities of trying to integrate both social concerns and performance objectives into a single portfolio. In addition, it holds other advantages as well, such as enabling the client to isolate a particular area of social concern and identify a fund, ETF, or managed account that specifically addresses that objective.

Many ESG-focused investors are even willing to forgo their usual performance requirements in order to allocate some part of their assets to causes they feel strongly about but that are characterized by companies that may be less profitable overall or have lower margins than their competitors. For example, a company that provides more sustainable packaging solutions might serve the environment much better but cost more to the packaged goods companies it supplies. And you might have clients that are just fine with that type of trade-off for either of the two companies.

The numbers show that many investors are already thinking this way about ESG-focused ETFs. Net inflows to such ETFs were about $9 billion in 2019. For 2020, they will exceed $30 billion.

Incorporating personal and societal goals into investing is perhaps one of the most positive developments to hit the investing world in decades. But financial advisors will bear the brunt of incorporating this new batch of perceptions, beliefs, and personal biases into sound investment planning. Once they accept that these goals are not entirely related to performance and treat them somewhat differently from a client’s overall financial goals, advisors may find that they have greater success in managing client expectations and satisfaction in this important and growing area.

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.