Client defections are not just about portfolio losses—they’re also about ‘regret’

Client defections are not just about portfolio losses—they’re also about ‘regret’

Classic finance theories do not address client emotions, yet loss aversion and regret aversion can be prime reasons why clients leave their advisors. Behavioral finance and game theory have answers.

Portfolio performance, market performance, and human emotions are intertwined in ways that provide ongoing challenges for advisors. While classic finance provides solid foundations for long-term portfolio management, it doesn’t address the shorter-term emotional factors related to performance that cause clients to walk. To manage client retention, advisors need ways of addressing these emotional factors. The good news is that there are some.

Most clients buy into the long-term view and accept year-to-year performance uncertainty as unavoidable. But even patient investors have their pain points. That pain comes in two forms: the pain of actual loss and the pain of opportunity loss. Both can lead clients to abandon their advisors. But advisors tend to focus much more on the former than the latter.

The economic environment in 2023 brings heightened challenges to advisors in retaining clients because experts are split on whether the Federal Reserve’s actions will bring on a recession and how deep it could be. Bonds are suffering from the rate increases, while equities are wavering on the possibility of a recession.

On the back of a year when most people in these assets already lost value, the odds of client defections will likely increase if the current year falls short as well.

Aversions to loss and regret

Behavioral finance sheds light on how clients react to investment performance. It’s not so much about the level of return as it is about the context within which the client will view it and the emotions the client will feel as a result. That context is determined by the client’s expectations, reference points for comparison, and risk posture—all three of which will vary by client. It may seem daunting to understand this about every client, but advisors who don’t are placing client retention at risk.

Behavioral finance offers insights into these emotions, and game theory offers one way to determine when a client might experience them. We know, for example, that taking a loss or feeling regret are two insidious emotions that most people have a strong aversion to. That aversion causes people to make “irrational” decisions when they experience them and sometimes just to avoid them. Among those, one could argue, can be the decision to seek a new advisor.

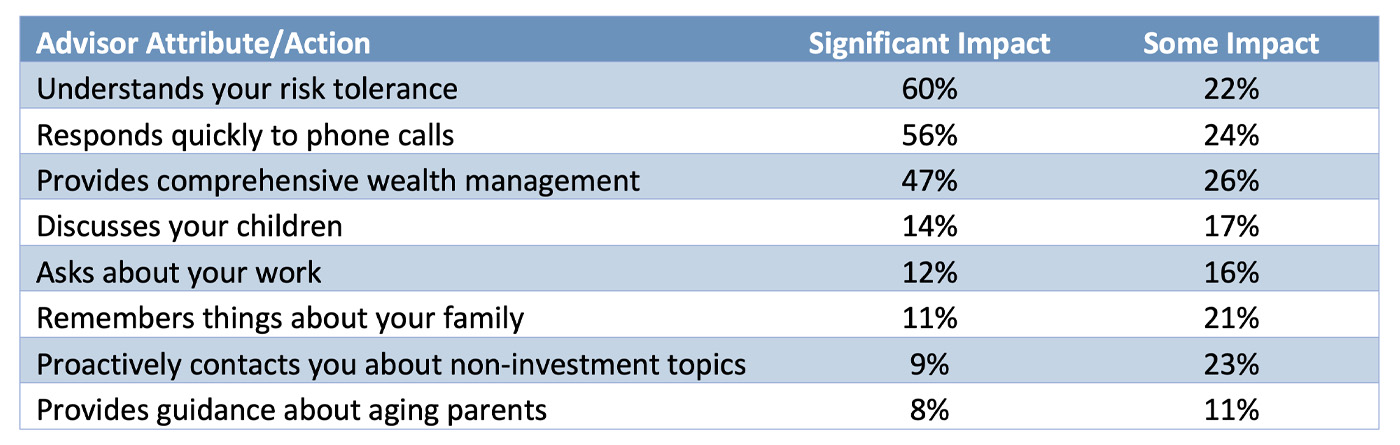

Both real and opportunity losses contribute to the perception that an advisor doesn’t fully appreciate the client’s risk tolerance—the main factor cited as an influence on client loyalty in Table 1 below.

TABLE 1: FACTORS THAT CAN INFLUENCE CLIENT LOYALTY

Source: Spectrem Group, November 2022

A client might walk from an advisor who gave them a 12% annual return if the market was up 20% that year. On the other hand, a client might praise an advisor who helped them achieve a 5% loss when the overall market was down 15%. The challenge for the advisor is to understand the context in which each client will evaluate their portfolio’s performance and the emotions they might feel as a result.

This may sound daunting for professionals trained in finance rather than psychology, but it doesn’t require a Ph.D. In fact, advisors already have tools available for managing client emotions—some are financial, and others simply involve asking the right questions.

Advisors may feel that because they cannot control the economy or the markets, they must accept the risk of losing a client due to underperformance as an unavoidable consequence. This does not have to be the case at all. Human emotions are based on relative values rather than absolutes, so the key to dealing with these aversions is understanding clients’ reference points and managing their expectations accordingly. There are no guarantees, but there are methodologies.

Loss aversion and regret aversion both deal with fear, and fear occurs before experiencing the relevant emotion. That’s actually good news because it gives advisors the ability to address them before they impact the client. Once a client experiences a regrettable loss or significant underperformance, that bell cannot generally be unrung.

In addition, clients understand these fears, and they can tell you whether their fear of loss is larger than their fear of missing out on the upside. They just have to be presented with possible market scenarios and properly asked relevant questions.

Advisors can help them transform those fears into expectations and strategies that reduce the risk of experiencing them. Once the advisor and the client are on the same page about the risks and opportunities in the current environment, the advisor has numerous ways of constructing a risk-managed portfolio designed around minimizing emotional extremes.

Loss aversion is the easier of these two emotions to identify and deal with. Regret is another matter.

The pain of regret

Psychologists will tell you that regret can be a very powerful emotion—one that has the ability to drive human behavior well beyond norms. In finance, it can be so strong that just the fear of it creates a behavioral bias that leads many investors to make irrational decisions.

A common form of regret aversion is the “fear of missing out” (FOMO). People who believe something has the potential for exceptional appreciation are often afraid they will regret not owning it and will buy it just to avoid that potential regret. Regret aversion can be exacerbated by other biases as well. When people you know are also buying such assets, regret aversion is compounded by herding bias. These two biases played a substantial role in the extreme run-ups in bitcoin and “meme” stocks.

To people who fall prey to these biases, the regret of not participating on the upside is actually perceived to be greater than the regret they might feel if they lose money instead. In other words, the fear of opportunity loss is greater than the fear of actual loss.

This is not the case for everyone, of course. Risk-averse and loss-averse clients will fear a potentially greater amount of regret from a potential loss than they would from missing out on a possible gain. Fear of regret thus works in two directions, driving client behaviors that can be entirely different, even when evaluating the same scenarios and potential choices. The key, therefore, to incorporating the “fear of regret” into an investment strategy lies in understanding which end of the regret spectrum a client falls on.

Importantly, both underperformance and opportunity loss can contribute to client dissatisfaction and cause regret, so a focus on strategies that won’t lose money only addresses part of one’s client base. To incorporate the fears of both real and opportunity loss, you need to focus on regret. The good news is that aversion to regret can work in the advisor’s favor because it can reveal what a client wants most to avoid, whichever type of loss that represents. Advisors might not always know the answer to that unless the question is specifically presented to the client, and there is a method for doing that.

Focusing on potential regret

The science of game theory (which inspired some of the work in classic portfolio theories used today) uses mathematical probabilities and employs protocols for making decisions in different types of games or risky situations. One of these protocols is called “minimax regret,” and it has application to investment decisions. Developed by John von Neumann in 1928, minimax regret can be used to make decisions that minimize the chance of having maximum regrets under various possible scenarios.

You might think that minimizing the chance of experiencing regret means the same thing as minimizing the chance of the greatest loss. That’s only partially true because minimax regret also considers that sometimes the greatest amount of regret comes from a choice that creates an opportunity loss as well.

An example can illustrate how minimax regret works. Consider this simplified forecast for the next year: Equities are expected to return as much as +15% or as little as -15%. Short-term bonds are yielding 5% but could potentially lose some value as rates rise, possibly returning only 2%. Twelve-month T-bills are yielding 4.5%.

If we assume the odds of the best- and worst-case scenarios occurring are each 50% for simplicity, then the expected return from stocks equals zero, the expected return from bonds is 3.5%, and T-bills would return 4.5%. On that basis, efficient market logic says the asset of choice should be T-bills.

But expected returns are simply statistical projections based on estimates. They hold a great deal of potential variance, and the variation is sufficiently large to create significant regret for investors in the wrong assets. A pension fund might be fine playing the long-term odds with a highly diverse portfolio, but individual assets are more concentrated, and their owners are far more susceptible to the emotions that result from either real or opportunity losses in the short term. In addition, the probabilities of different scenarios occurring are highly subjective, and clients may not agree with their advisors on either the probabilities or the magnitudes of the best- and worst-case situations.

The minimax-regret approach ignores the probability of the best- or worst-case scenarios occurring, so disagreements on that are eliminated. Its only concern is the potential magnitude, as that is what will cause regret. It does, however, consider the magnitudes of both best-case and worst-case scenarios, recognizing that opportunity loss also causes regret.

Clients for whom any losses are unacceptable should be relatively comfortable with a 4.5% return, regardless of where stocks go. But clients who are more risk-oriented could experience heavy regret if they are sitting in T-bills while stocks rally 15%. A decision process that points out the potential regrets from either losses or missed opportunities thus becomes a useful tool for identifying which regrets the client fears the most.

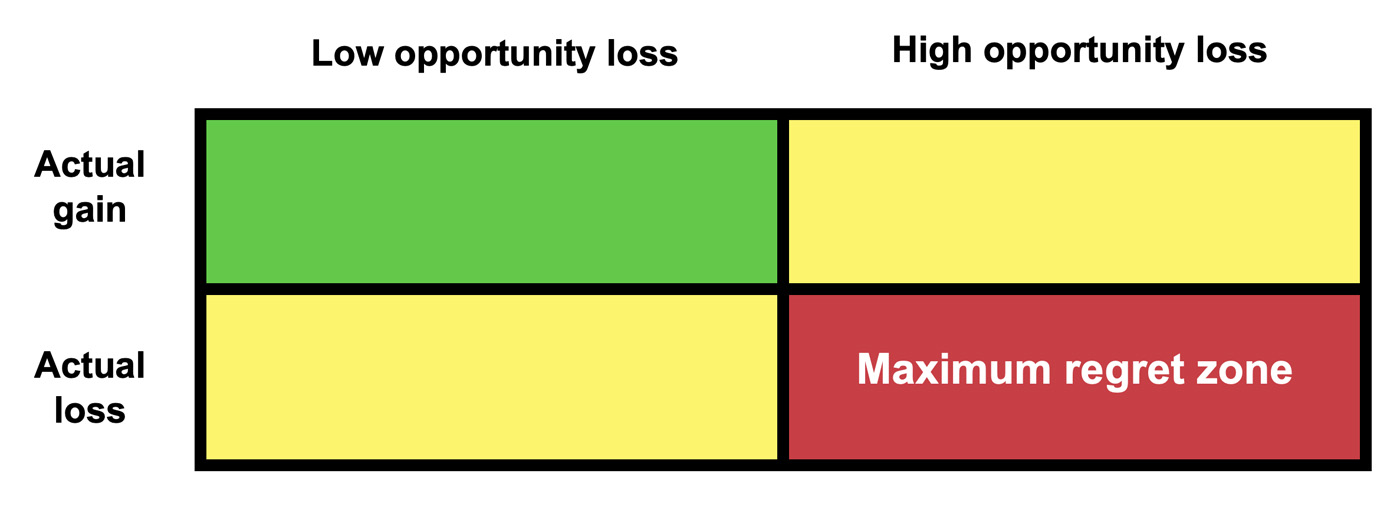

FIGURE 1: CONCEPTUAL MODEL IDENTIFYING THE ‘MAXIMUM REGRET ZONE’

Source: Richard Lehman

The minimax-regret decision protocol doesn’t attempt to build mathematically optimal portfolios. It attempts instead to help the client envision different scenarios and to express a preference for a strategy that minimizes their potential regrets. Armed with that information, the advisor can create a portfolio that either addresses those regrets directly or balances them with potential opportunities.

In the absence of a focus on regret, advisors tend to assume that clients’ main concern is avoiding loss. This group may indeed be larger, but addressing loss aversion across the board risks being too conservative with some clients and potentially exposing them to the regret of missing upside. That potential regret can then become reality as well, with a client remaining too long in a defensive stance and missing out on real gains when the market roars back after a significant decline.

Using the minimax-regret decision protocol won’t create a foolproof portfolio or guarantee client satisfaction, but it provides a simple way of getting a client to reveal their worst fears about the performance of their portfolio. Providing that input has the dual effect of making the client more likely to accept their performance results later and less likely to blame the advisor for what they end up with. In addition, it gives the advisor a good starting point for managing the client’s assets in uncertain environments. Advisors cannot stop clients from feeling emotions about their performance, but they can mitigate the chances these emotions will lead to a client defection.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Proactive Advisor Magazine. These opinions are presented for educational purposes only.

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.