The power of planning: A behavioral perspective

The power of planning: A behavioral perspective

A lack of sound financial information, behavioral biases, and emotional decision-making can impair wealth creation for many people. Behavioral coaching can help investors create, implement, and stick to disciplined financial and investment plans.

Now, more than ever, financial planning is a powerful tool to help investors succeed and achieve better outcomes.

The daily stream of events and the accompanying wave of pundit opinion can take its toll on weary investors and leave them in a state of angst about the markets and their investments. Planning is a powerful tool that helps investors to refocus on their long-term goals and stay on track.

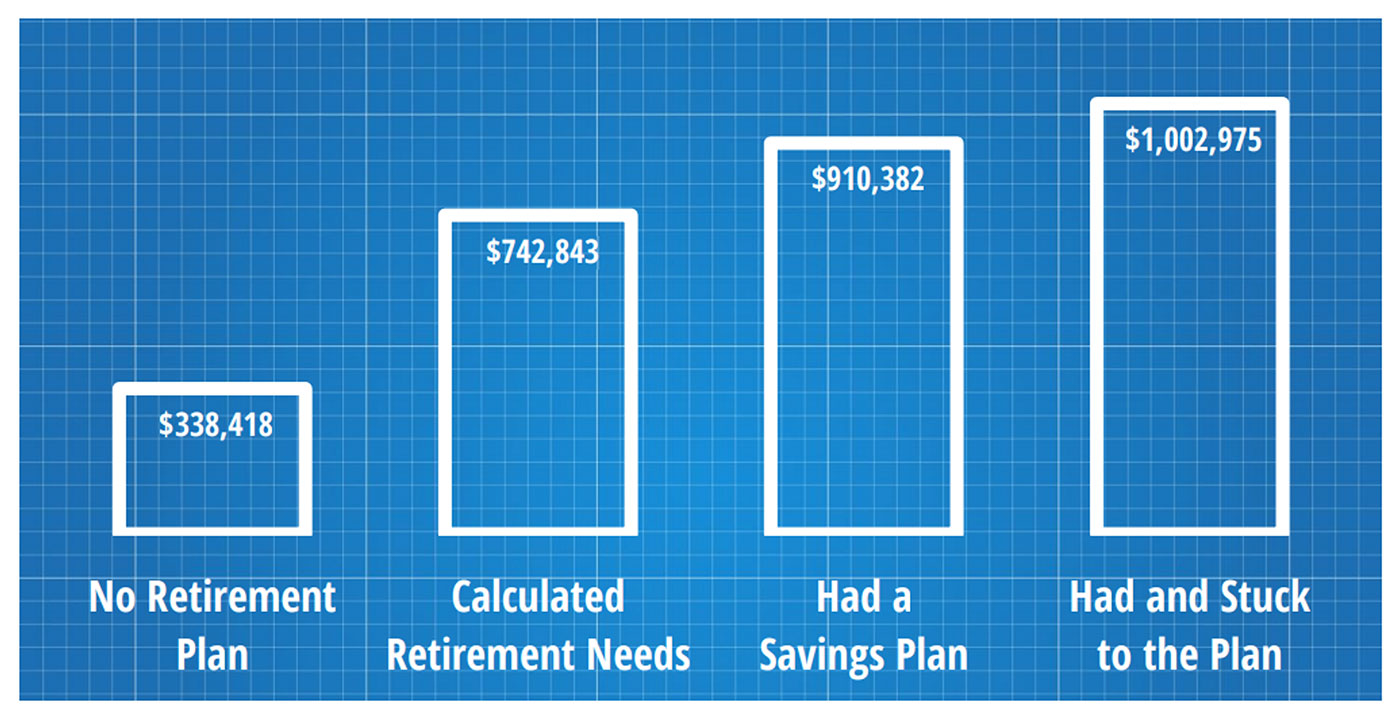

A still-relevant research study first released in 2011, “Financial Literacy and Planning: Implications for Retirement Wellbeing,” analyzed four categories of planning and their impact on the net worth of individuals or families.

These categories were:

- Those who had no plan.

- Those who thought about planning by calculating how much they needed for retirement.

- Those that had a plan for how to save the money needed.

- Those that had a formal plan and stuck to it.

Figure 1 highlights the benefits of planning taken from the study, which focused on retirement planning among Americans over age 50—in a wide range of market conditions.

Source: Annamaria Lusardi and Olivia S. Mitchell, “Financial Literacy and Planning: Implications for Retirement Wellbeing,” working paper, National Bureau of Economic Research, May 2011

It is not surprising that having and sticking to a plan generates the best outcome. What may be surprising is the magnitude of the impact of planning and that any amount of planning results in two to three times the wealth. Even just calculating the amount of money needed for retirement improves results dramatically.

Having a plan simplifies investing and allows investors to focus on things they can control. Contributions, withdrawals, and the amount of time invested are all drivers of long-term wealth. These actions are enabled by planning, which creates financial awareness, establishes realistic and achievable goals, and combines long-term thinking with consistent action over time. Putting current events in a longer-term context and focusing on what investors can control with practical planning can help to relieve stress and avoid costly mistakes.

Strong emotions and behavioral biases often can cloud the thinking of the best-intentioned investors. These might include anchoring (relying too much on one specific piece of information or belief); loss aversion (the fear or pain of losses becomes overwhelming); and the many forms of cascading, recency, and availability bias (how one processes flows of information to make decisions).

With daily headlines and dramatic story lines, it often feels like our wealth and fate hang in the balance. Our minds react to new information, and we project potential extreme outcomes and feel compelled to act. To put things in perspective, long-term stock returns average around 10% per year, including all the major historical events, recessions, and bear markets. Tune out the noise!

In the case of overconfidence bias, we are prone to see information and data in patterns and believe we have profound insights from simple observations. We are particularly subject to information that confirms our existing ideas. In reality, most of what lies ahead is uncertain and random. We will be drawn to things that happened to work out during any particular period of time and be tempted to abandon anything that has not fared well recently, regardless of its long-term value.

We are all prone to emotional overreaction when under stress because our cognitive functions are diminished by our emotions. For investors, this can lead to poor decisions at precisely the wrong time and often results in costly mistakes.

Building wealth requires discipline and delayed gratification, where current benefits are traded off for long-term benefits. We are unlikely to engage in this trade-off without “System 2” thinking, which requires a conscious and rational process that identifies future value and a method for obtaining it.

Beyond the important area of how investors manage their investments in a disciplined fashion—whether self-directed or with a financial advisor—through the daily and yearly ups and downs of the market and news cycle, two specific behavioral issues can create further barriers to sound wealth creation over the long term.

Investors should not hesitate to build their wealth

Investors often fret about the current market environment and ask if they should invest now or hold off for “a better time.” They often wonder if they are committing capital near a market top and think they will be better off by trying to time their investment contributions according to their perceptions of how the market might perform over the coming months.

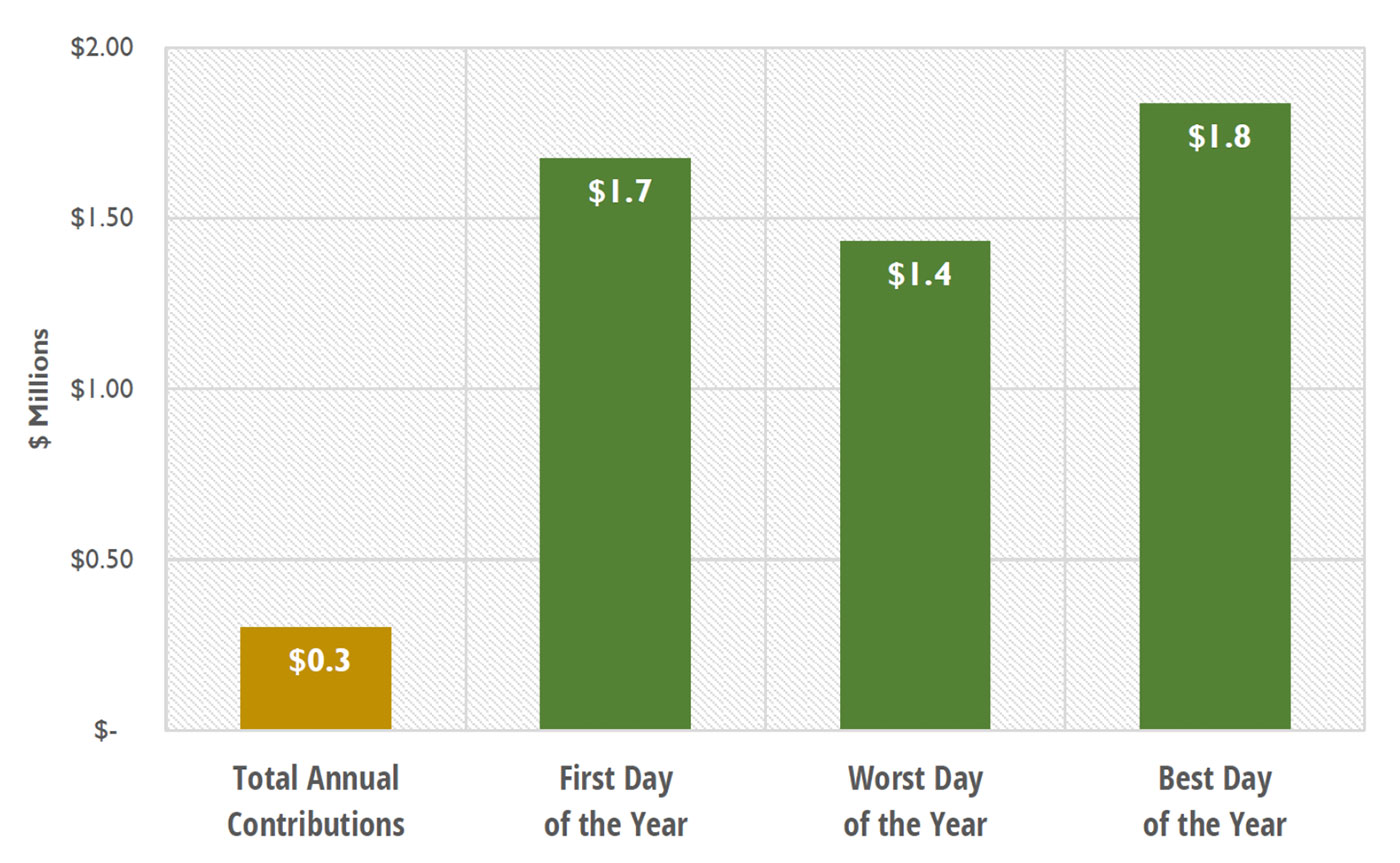

For long-term investors, making regular contributions is more important than when the contributions are made each year. Figure 2 shows there is not much gained by perfectly timing contributions each year.

FIGURE 2: 30-YEAR OUTCOMES OF CONTRIBUTING CAPITAL ON SELECTED DAYS

(S&P 500 TOTAL RETURN INDEX 1990–2019)

Source: AthenaInvest Inc. and S&P Dow Jones Indices LLC

Figure 2 summarizes the outcomes of making annual contributions of $10,000 over three decades, encompassing a diverse array of market conditions.

In the first scenario, each annual contribution is made on Jan. 1. The second scenario shows the result of contributing on the day of the market high for the year, “the worst time.” Finally, the third scenario shows what happens when the annual contribution is perfectly timed at the market low for the year, “the best time.”

If you simply make the investment on Jan. 1 each year, the $300,000 contributed over the 30-year period will have grown to an impressive $1.7 million. Absolute perfect timing either way, the best or worst day each year, results in a range from $1.4 to $1.8 million.

Investing on exactly the right or wrong day every year for 30 years in a row is not a realistic scenario. This analysis shows that making regular annual contributions and compounding are the main drivers of wealth, not the timing of the contributions. Sticking to a long-term plan and making regular contributions is the most reliable way to build wealth over time and, more importantly, contributions are squarely within an investor’s control.

Being disciplined with unexpected ‘windfalls’

Investors spend a lot of time and energy thinking about the next big market crash or how to avoid large losses. The opposite side of that coin is what to do when faced with large, unexpected investment gains or a windfall from another source, such as an inheritance or bonus. It’s natural to want to spend at least some of this “free money.”

But before an investor rushes out to buy something right now, like a new vehicle, or put a down payment on a vacation home, major home renovation, or a new boat, they should take the time to think about the advantages of delaying that immediate gratification.

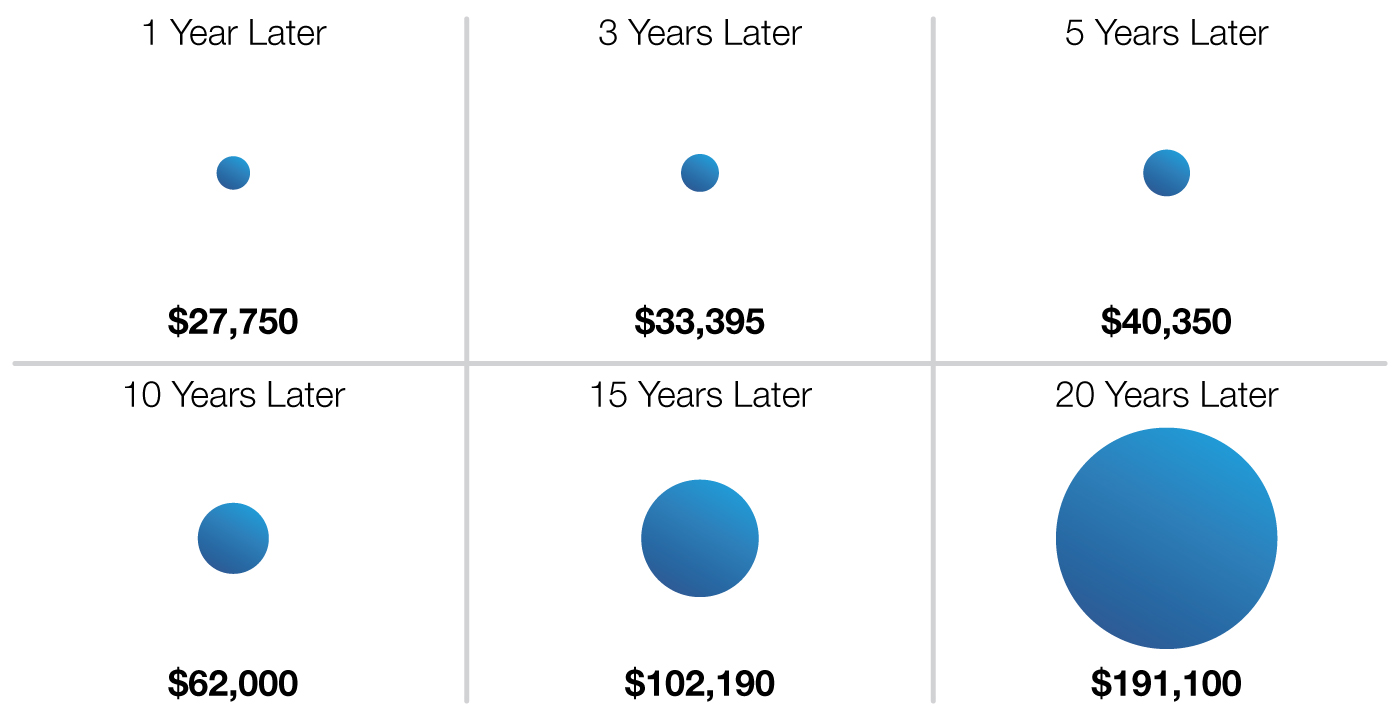

Let’s assume an investor started a year ago with a $50,000 investment portfolio that appreciated by 50%. That portfolio is now worth $25,000 more, or $75,000.

What if they bought something with that $25,000 gain, maybe a car?

To illustrate the trade-off of buying something now versus waiting, Figure 3 shows how much one could afford over different time periods (ignoring the impact of inflation on the future price) if he or she resisted the temptation to buy that brand-new $25,000 car now and instead invested their money. Waiting just three years could put you into a much higher-end vehicle. Wait a decade and that convertible luxury sports car could be yours. And patiently waiting 20 years might turn an impulsive $25,000 purchase into a bona fide supercar.

Note: Performance used to calculate ending values are average rolling-period returns compounded by geometrically linking monthly returns including reinvestment of dividends.

Source: Fama-French Market Return Series, Jan. 1, 1927–Dec. 31, 2020

But, of course, new cars aren’t the point here. What matters is the cost of spending $25,000 today increases with time, by doubling in seven years and finally ballooning to nearly $200,000 over 20 years when measured against investing that same amount. Lastly, from an investment perspective, it should be noted that large market gains in short time frames are part of the historical gains in the stock market. They are integral for offsetting losses and building long-term wealth, and are really not “windfalls.”

There are often compelling reasons for a major expenditure in the here and now, not the least of which is how much personal satisfaction it might bring. However, being financially aware—and responsible—simply means fully understanding and accepting the trade-offs involved in any decision of this magnitude.

Numerous academic and industry studies over the years have documented the value of professional financial planning and the benefits it can bring to individuals and families.

One such study, “Planning for the 30+ Year Retirement,” published jointly by Wells Fargo Wealth & Investment Management and the Stanford Center on Longevity, states, “One of the keys to enjoying a long, fulfilling retirement lies between our ears: having a ‘planning mindset’ is a powerful predictor of personal well-being and overall financial wellness.”

The challenge for financial advisors is helping their clients—especially those facing retirement—to reconcile their practical need for capital appreciation with their strong emotional desire for capital preservation.

This requires not only technical expertise and knowledge from a financial-planning perspective, but also being able to provide behavioral guidance that helps clients to avoid or minimize emotional decision-making that can derail even the best-constructed financial plan.

Financial professionals can help their clients from a behavioral perspective by doing the following:

- Working collaboratively to develop a needs-based plan as a financial road map and illustrating in tangible terms the economic value of following the plan. Help clients to develop specific guidelines for planned contributions and withdrawals and review spending decisions and timing in the context of overall goals.

- Helping clients specify realistic and achievable plan objectives, reviewing and updating the plan regularly as their life circumstances undergo inevitable change.

- Discussing predetermined courses of action to help clients develop discipline around their investment plan. Help clients to focus on what they can control, recognizing there will always be unexpected market or economic events.

- Providing sound counsel during both market highs and lows, helping investors avoid poor investor behavior and overreaction. Make sure clients understand the risk-management elements of their plan during the development phase of the investment plan—and how these align with their specific risk profile. Have a disciplined investment process with a growth portfolio designed to be resilient over a wide range of market conditions.

- Reinforcing with clients that progress toward goals is almost always more important than short-term investment performance—or comparisons with an arbitrary market benchmark.

***

The short-term decision to contribute to or withdraw from an investment portfolio has a magnified impact on our long-term wealth due to the power of compounding over many years. On the other hand, the highly emotional short-term timing of when we make contributions or withdrawals has a negligible long-term impact. That is, long-term compounding trumps short-term timing.

The surest path to successful wealth building is creating, implementing, and sticking to a well-thought-out financial plan. A plan provides a valuable framework for making trade-offs between short-term actions and long-term results. In addition, it serves as a set of concrete actions that can be taken to achieve long-term goals. A good plan gives investors the best opportunity to achieve their financial goals, along with contributing to a good night’s sleep!

C. Thomas Howard, Ph.D., is the founder, CEO, and chief investment officer at AthenaInvest Inc. Dr. Howard is a professor emeritus in the Reiman School of Finance, Daniels College of Business at the University of Denver. Dr. Howard is the author of the book “Behavioral Portfolio Management” and co-author of “Return of the Active Manager.” AthenaInvest applies behavioral finance principles to investment management and also provides advisor coaching and educational resources.

C. Thomas Howard, Ph.D., is the founder, CEO, and chief investment officer at AthenaInvest Inc. Dr. Howard is a professor emeritus in the Reiman School of Finance, Daniels College of Business at the University of Denver. Dr. Howard is the author of the book “Behavioral Portfolio Management” and co-author of “Return of the Active Manager.” AthenaInvest applies behavioral finance principles to investment management and also provides advisor coaching and educational resources.