Managing investments in emotionally charged markets: A behavioral framework

Managing investments in emotionally charged markets: A behavioral framework

Is it time to move away from the efficient market hypothesis to a more realistic representation of markets? Viewing stakeholders as emotional decision-makers, rather than rational computational entities, will help in navigating a changing financial environment.

“Indeed, we have to distance ourselves from the presumption that financial markets always work well and that price changes always reflect genuine information. … The challenge for economists is to make this reality a better part of their models.”

— Robert Shiller, “From Efficient Markets Theory to Behavioral Finance”

Professor Shiller wrote these words in 2003. But he could just as easily have written them today in light of the recent wild swings in the stock market.

The prevailing theory of efficient markets assumes that stock prices reflect a company’s valuation, but activity over the last couple of months clearly demonstrates the role that emotions play in buy and sell decisions. Eventually, these highly charged emotions will dissipate as solutions to the coronavirus-induced lifestyle are introduced. The impact of behaviors on market activity, however, will not subside. They are present in everyday trading patterns. This article provides a framework for viewing the behaviorally driven decisions so commonly made by investors.

Ten years later, Professor Shiller received the 2013 Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences for his pioneering behavioral finance research, sharing the prize with Lars Peter Hansen and Eugene Fama. Naming Professor Fama as co-recipient created a Machiavellian buzz in anticipation of the award ceremony, as Shiller had described Fama’s efficient market hypothesis as “the most remarkable error in the history of economic thought.” Who says the Nobel committee does not have a twisted sense of humor?

The shift to behavioral finance received a further boost in 2017 when the Nobel Memorial Prize in Economic Sciences was awarded to Richard Thaler of the University of Chicago, also home to Fama. Throughout his career, Thaler focused on the cognitive errors made by individuals and how government and business policy can be revised to “nudge” people to make better decisions. Thaler and Fama are good friends and regularly golf together. Most likely, the efficient market hypothesis joins religion and politics as taboo topics of discussion.

The years since Shiller’s statement have seen an avalanche of new academically verified pricing anomalies, further challenging the notion “that price changes always reflect genuine information.” This has now gotten to the point that we have to wonder if collective cognitive errors are the primary drivers of investment returns, displacing new information as the most important driver.

As Shiller suggests, it is time to move away from the efficient market hypothesis, one of the pillars of modern portfolio theory (MPT), to a more realistic representation of financial markets and human behavior.

Viewing investors and markets as emotional decision-makers rather than as rational computational entities forces us to reconsider every aspect of how we operate in financial markets. Markets are a complex system, consisting of a composite of countless individuals and their decisions and actions, each influenced by a wide array of emotions, behavioral biases, and cognitive errors. The behavioral factor markets (BFM) concepts below provide a framework for rethinking markets and investment management.

We have difficulty understanding why markets and their underlying securities move the way they do over shorter periods. Volatility will likely be present during much of 2020, and the day-to-day swings that occur will have no simple, logical explanation, as is often the case. This is disconcerting because we are investment professionals and our clients expect us to understand and explain what can be unsettling, if not downright terrifying, market movements. But the truth is that the vast majority of individual security and market movements are unexplainable because they are driven by emotional crowds, elevated by uncertainty and under- and overreaction.

An entire media and professional ecosystem has grown up to fill this information void. Market events are continuously ascribed to one new piece of information or event. People understand the world by means of stories, and the more detailed the story, the more believable it becomes in the eyes of the public. Interestingly enough, more detailed stories are much more likely to be wrong, highlighting one of the many cognitive errors so frequently observed.

Recently, the world’s response to the coronavirus has roiled financial markets. But beyond acknowledging this broad cause, it is very difficult to explain specific extreme volatility, other than attributing it to emotional crowds.

So, when investors ask us why the market, a stock, or other security moved the way it did on a particular day, the honest answer is most often, “I have no idea.” Unsettling as this may be, it is the consequence of the first BFM concept: emotions—not fundamentals—are the main movers of financial markets. This admission is the first step toward a more realistic market view. Financial markets cannot be easily explained or neatly packaged into a set of mathematical equations. Markets are noisy and largely unpredictable, and the only way to operate successfully in them is to avoid being fooled by this messiness.

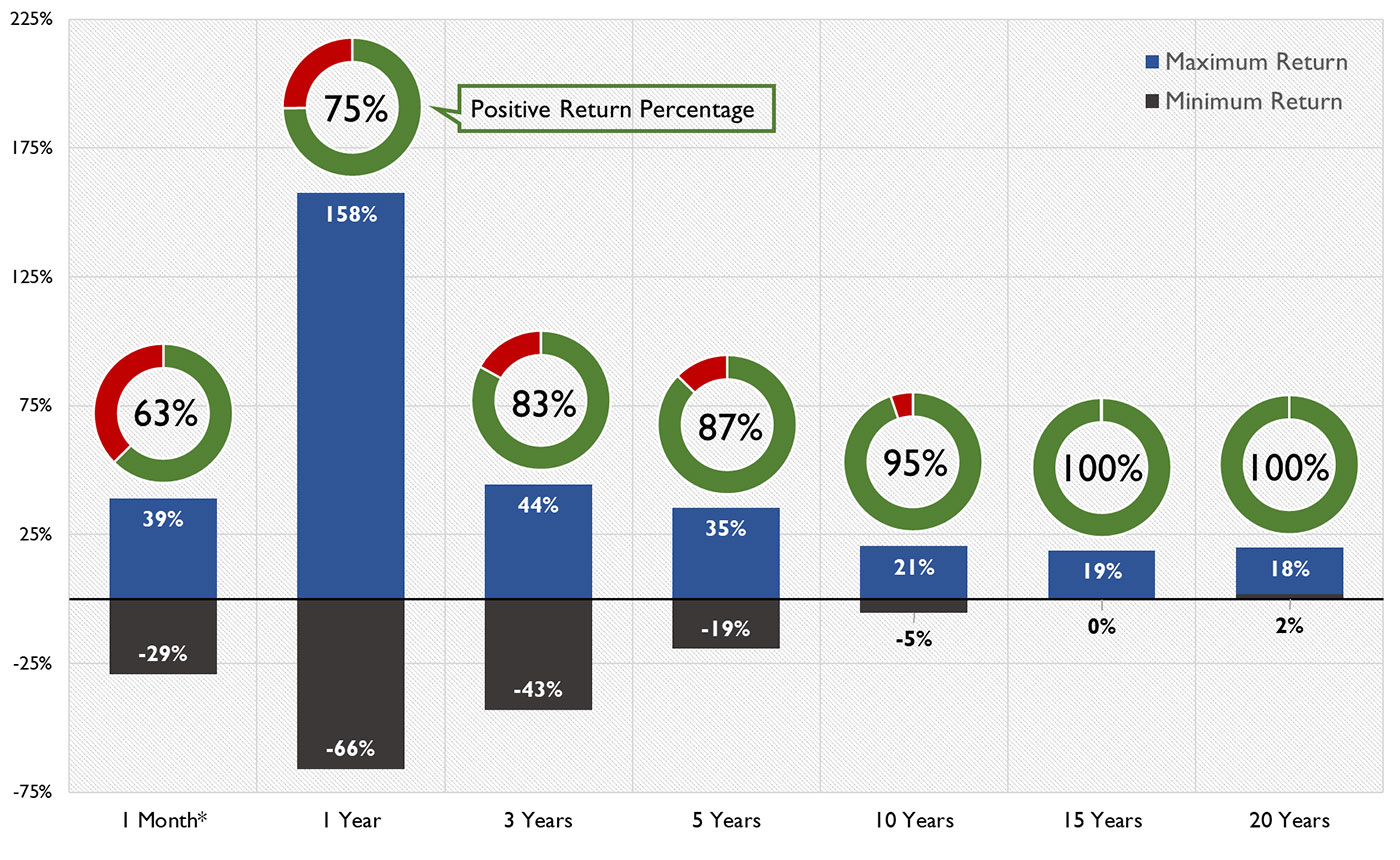

This messiness is apparent in the following chart, which shows that return volatility declines with the holding period. One-year rolling returns range from a low of -66% to a high of 75%, while 20-year average annual returns range from a low of 2% to a high of 18%. The one-year return range reveals the dramatic impact of emotional crowds, while the 20-year returns are largely driven by economic fundamentals. That is, emotional crowds dominate short-term, even one-year, returns, while fundamentals play a minor secondary role. The reverse is true over the long term.

Note: Month returns are not annualized. Figures include dividends and are compounded by geometrically linking monthly returns.

Source: AthenaInvest, based on data from Fama-French Market Return Series

These concepts run counter to the major pillars of 20th-century financial theory: that investors are expected-utility maximizers and market prices reflect all relevant information.

Behavioral research decimates the concept of the expected-utility maximizer. It is virtually impossible for an individual to collect all of the needed information and then accurately process that information to come up with a rational decision. This is known as “bounded rationality,” first introduced by economist Herbert Simon. Even more damaging, Daniel Kahneman, Amos Tversky, and others convincingly demonstrate that even when all information is available, individuals are highly susceptible to cognitive errors. As Kahneman and Tversky concluded after years of research, human beings are by and large irrational decision-makers.

Since we are strongly predisposed to make cognitive mistakes due to our emotions, it takes only a small step to conclude that markets cannot be informationally efficient. The evidence supporting this conclusion is vast: There are hundreds of statistically verified anomalies in the academic literature and more continue to be found. And markets are more volatile than is justified by changing fundamentals and information. The result is a bleak picture: emotional investors, burdened by cognitive biases, with a penchant for herding, regularly driving prices away from underlying fundamental value.

Unexpectedly, analyzing investors and markets through a behavioral lens provides a more reliable framework. Why? Because individuals rarely change their behaviors. And investing crowds are even less inclined to alter their collective behavior.

Portfolio managers and analysts can build strategies based on measurable and persistent behavioral factors, frequently using fundamental data as an objective proxy for these factors. The well-known fact that individuals and groups are loath to change their behavior means these funds have an excellent chance of long-term outperformance.

Consultants and gatekeepers can focus on behavior as well. They need to create incentives to encourage high-performance behavior by investment managers. According to academic studies and industry analysis, including my own research, these behaviors include consistently pursuing a narrowly defined strategy, while taking only high-conviction portfolio positions. To date, the focus has been on reducing short-term volatility and tracking error. Changing incentives will lead to funds behaving in a way that builds long-horizon wealth for investors.

Collective, emotionally driven behavior is the foundational concept underlying financial markets. Markets are populated by human investors burdened with emotional baggage and associated cognitive errors. These errors are amplified inside a market due to herding, leading to significant price swings. Rampaging emotional crowds are the cause of excess return volatility, as we have seen illustrated so well recently. As Shiller points out in his book “Irrational Exuberance,” you need look no further than price bubbles in the equity market for evidence of the dramatic impact of emotional crowds.

Of course, economic, political, international, and market information flows continuously into markets. In times past, it was thought that the arrival of these pieces of new information was the primary reason prices moved the way they did, as participants rationally processed and repriced securities. But this idyllic concept has now been shredded and replaced with emotional crowds and cognitive errors as the most important drivers.

For example, when a significant event like the recent coronavirus outbreak triggers our emotions, most of us react in a similar way. This collective response is further amplified by herding. Indeed, herding can occur even without an external event. We collectively react because we see everyone else reacting, even though we do not know the reason for the exact sudden stampede.

Emotional crowds rampaging in markets create numerous opportunities for professional investors who are not caught up in the moment. I refer to these opportunities as behavioral price distortions.

Alternatively, these are dubbed “anomalies” in the academic literature because their existence is inconsistent with the efficient market hypothesis. When they are included in asset pricing models or in constructing smart beta portfolios, they are called “factors.” I prefer the term “behavioral price distortions” because they are the consequence of collective emotional behavior.

Distortions are the ingredients active managers use when creating an investment strategy. In the case of smart beta, they are the entire strategy. For other active managers, they represent only a portion of the strategy because an investment manager’s “recipe” or decision-making process makes up the rest. Behavioral price distortions are essential to successful active management.

Fundamental information, rather than being front and center, works behind the scenes in the investment process as a proxy for behavioral price distortions. With a long enough perspective, it also influences the returns of individual securities and markets. In the long run, fundamentals matter. The most economically successful companies earn the highest return over the long run, and the reason the stock market goes up over time is directly related to growth in the underlying economy.

The pecking order has changed, with emotional crowds dominating prices and returns over shorter periods, and with fundamentals holding sway only over longer periods. For those who spend time making investment decisions, this is not surprising, but it is where many opportunities lie.

Once it is accepted that emotional crowds, rather than fundamentals alone, are the most important drivers of price changes, traditional economic modeling approaches break down. To apply such an approach, it is necessary to posit what investors are attempting to maximize, such as expected utility. Even if we assume they are attempting to maximize utility, they will be influenced by emotions, behavioral biases, and cognitive errors. Behavioral models that specify investor maximization remain the province of theoretical academics and, up to this point, have yet to yield usable results.

Another problem is that security prices and volatility are polluted by investor emotions, so virtually all of the quantitative measures in current use, such as beta, efficient frontier, and Sharpe ratio, among others, are problematic for managing and evaluating investment portfolios. Shiller and others have shown that volatility is largely driven by emotion, not fundamentals. So, beta is actually capturing nondiversifiable market emotions, while both the efficient frontier and Sharpe ratio are emotion-return, not risk-return, measures. It is important to avoid baking investor emotions into our analytic tools.

Portfolio managers and their analysts must deal with emotions at several levels. When building an investment strategy, only those behavioral price distortions that are measurable and persistent based on careful and thoughtful analysis should be accepted. For example, while Fed actions and interest rates are often put forward as reasons for market movements, there is precious little evidence of consistent causality.

The goal is to focus only on those distortions supported empirically by large data or real-world experience while ignoring everything else. As a result, investment teams become expert at filtering the signal from the considerable noise in the market. This means they may not be able to explain daily events, but they are able to deliver long-horizon wealth to investors. Consistent, predictable behavioral patterns and responses can be identified, such as overreacting to analyst downgrades for example.

In implementing a strategy, it is important not to succumb to the same emotions that influence nonprofessionals. For example, do not fall in love with your investments; instead, remove the emotions by developing an objective selling rule. Considerable research showing how fund managers can avoid making the cognitive errors so detrimental to portfolio returns now exists.

For consultants and gatekeepers, the challenge is to avoid baking investor emotions into the criteria used for adding and evaluating managers. Individuals react strongly to short-term volatility and drawdown as well as tracking error, even when facing a long time horizon. These emotions are best dealt with by advisors through careful financial planning.

But many in this position respond to the lowest common denominator by expecting every fund to manage each of these emotional triggers by reducing short-term volatility and tracking error. This results in underperforming portfolios and a reduction in long-horizon wealth. Investors pay a high price when emotional catering is demanded of every fund.

Advisors recognize that emotions and the resulting client behavior are particularly important to building wealth for clients. A behavioral wealth advisor (BWA) designs their practice to manage behaviors at each stage of the client service model, improving both the opportunity for client wealth accumulation and differentiation of their practice.

The BWA employs a unique discovery process that obtains both financial and emotional data to create a financial plan and a behavioral profile that helps determine the best approach to working with a client. The financial plan is constructed using a needs-based approach with a separate portfolio built for each need, clearly differentiating for the short and long term. This initial planning phase is critical to removing the investor’s emotional errors from the wealth-building process.

For the growth portion of the portfolio, the focus is on a long investment horizon. The task of the advisor is to encourage clients to adopt a long-term view while avoiding emotional reactions to short-term events. Evidence indicates that such myopic-loss-averting decisions have a profoundly negative effect on wealth. Emotional coaching is one of the most important services an advisor can offer clients.

If needs-based planning is successful, the money allocated to the growth portion of the client’s portfolio can be largely invested in securities with a high expected return but also short-term volatility, such as equities. Admittedly, it is a challenge to keep clients fully invested, while avoiding costly trading decisions, when markets turn volatile.

The BWA identifies solutions to meet both broad and specific needs, including external expertise such as catastrophic risk management and estate planning. Their goal is to give clients the confidence that all aspects of the financial plan are appropriately considered and managed in an integrated and organized fashion. Organization is also important in progress meetings, as is discipline. Both help keep the client focused and reinforce that the maintenance of a plan is just as important as its creation.

Recognizing that we are all strongly predisposed to make emotional mistakes, it is logical to conclude that markets cannot be informationally efficient. As this article details, analyzing investors and markets through a behavioral lens provides a more reliable framework than the conventional approach of MPT.

Shiller’s point about the dramatic impact of emotional crowds is demonstrated today with investors’ reaction to the coronavirus pandemic and the resulting extreme volatility. Many advisors are providing behavioral coaching to prevent emotional decisions by clients that will result in significant portfolio losses. Taking the approach of a BWA can strengthen that effort by using behavioral finance discipline throughout the client service model.

At the same time, portfolio managers and their analysts must also work to avoid the influence of emotions. When building an investment strategy, accept only those behavioral price distortions that are measurable and persistent based on careful analysis and supported empirically by a large amount of data or real-world experience, ignoring everything else. For consultants and gatekeepers, it is most important to avoid baking investor emotions into analytic tools.

Taking liberties with Professor Shiller’s quote earlier, “The challenge for financial professionals is to make this reality a better part of their models.” In other words, see markets as they are rather than how we would like them to be. We should expect the analytical tools derived from behavioral finance’s more realistic representation of financial markets and human behavior will eventually replace the MPT tools in use today.

Editor’s note: Proactive Advisor Magazine wants to thank Dr. Howard and AthenaInvest for contributing this article to our publication. Please visit AthenaInvest to register for a monthly “Behavioral Viewpoints” article.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Proactive Advisor Magazine. These opinions are presented for educational purposes only.

Past performance does not guarantee future performance. These views represent the opinions of AthenaInvest Inc. as of the date of publication and are subject to change depending on subsequent developments. Nothing contained herein is a solicitation to buy or sell securities and should be used for informational purposes only.

C. Thomas Howard, Ph.D., is the founder, CEO, and chief investment officer at AthenaInvest Inc. Dr. Howard is a professor emeritus in the Reiman School of Finance, Daniels College of Business at the University of Denver. Dr. Howard is the author of the book “Behavioral Portfolio Management” and co-author of “Return of the Active Manager.” AthenaInvest applies behavioral finance principles to investment management and also provides advisor coaching and educational resources.

C. Thomas Howard, Ph.D., is the founder, CEO, and chief investment officer at AthenaInvest Inc. Dr. Howard is a professor emeritus in the Reiman School of Finance, Daniels College of Business at the University of Denver. Dr. Howard is the author of the book “Behavioral Portfolio Management” and co-author of “Return of the Active Manager.” AthenaInvest applies behavioral finance principles to investment management and also provides advisor coaching and educational resources.