Bear market behavioral biases—are you sure about that?

Bear market behavioral biases—are you sure about that?

Bear markets trigger powerful emotions for many investors. Awareness of investor biases—which are compounded in bear markets—can help both advisors and their clients avoid making behavioral mistakes in turbulent times.

It might seem strange to be thinking about a bear market when the U.S. equity market has recovered impressively from the 2020 COVID-induced market swoon. But the current environment of strong market returns is the best backdrop for thinking about how you—whether an advisor or individual investor—should respond to the next bear market (typically defined as a drop exceeding 20%).

Such events trigger powerful emotions that lead to poor investment decisions. As an example, we had a financial advisor pull millions of dollars out of one of our portfolios right at the bottom on March 23 last year. He thus locked in a significant loss and, in turn, very likely missed much of the ensuing dramatic bounce back. This is one of the common patterns in such market movements: The largest gains follow closely on the heels of the largest losses. Locking in the large loss, then missing the large gain, is a wealth-destroying double whammy.

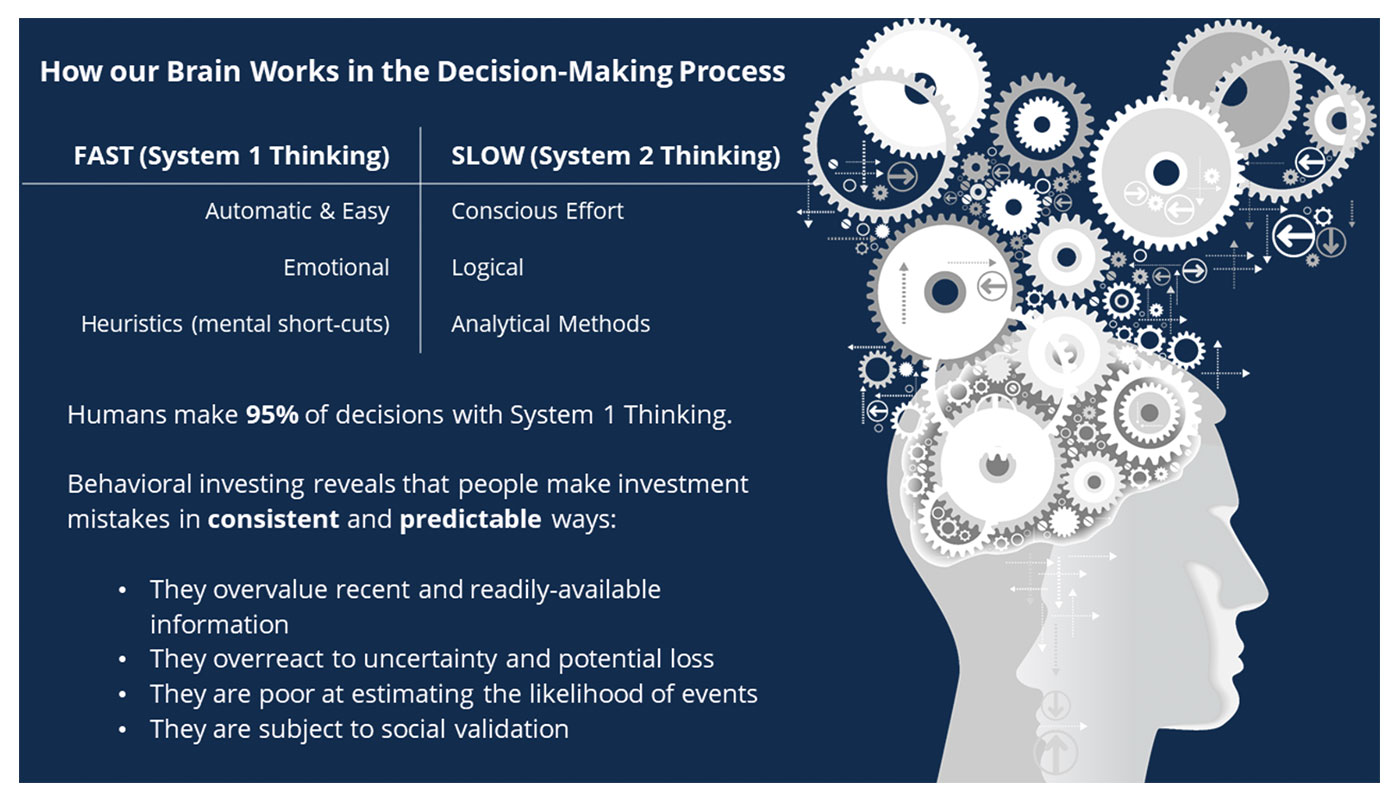

Over 95% of human decisions are made using “System 1 Thinking,” which is automatic and uses mental shortcuts. “System 2 Thinking,” by contrast, requires conscious effort with logical thinking and analytical methods

Long-term investing is often counterintuitive and requires a disciplined System 2 approach. Bear markets compound our normal biases, generating strong emotional triggers that can result in poor decision-making.

Source: AthenaInvest, based in part on the work of psychologist Daniel Kahneman

Awareness of these biases can help advisors and clients avoid making behavioral mistakes when influenced by powerful emotions. Some of the more common and costly bear market biases are listed below:

Hindsight bias. We all know the Monday-morning quarterback who knows exactly what play to call and is sure it would have succeeded. The same is true with bear markets—everyone believes we should have seen it coming and they would have done something different. Of course, very few people saw it coming, and even fewer had the systems and courage to act upon it. Who can really get it perfectly right on both the down and up sides of a bear market?

Availability cascade. With overwhelming daily headlines and dramatic storylines of disasters and heroes, when one faces a turbulent environment, it feels like that moment is all there is, and our fate hangs in the balance of every decision. Our minds race with each new bit of cascading information and projected potential extreme outcomes. In this regard, it is interesting to note the recent economic and market information revealing 2020 Cassandras as being too pessimistic, as is so often the case.

Loss aversion, anchoring, and regret. By nature, we feel twice as bad about a loss as we do an equivalent gain and are hardwired to overreact to any perceived loss. Of course, we also become anchored to peak values prior to the downturn, along with how much we lost and when we will get it back. We conjure up regret and torture ourselves with “should have, could have, and would have” scenarios.

Overconfidence bias. Given the disaster that has occurred, we promptly “take control” and perhaps fire our experienced investment advisors and managers. At this point, we can easily confuse luck with skill, and we substitute things that happened to work out during this short period of time with things that work consistently over time. We eagerly read the latest email or financial article promoting a magic elixir that can prevent or cure all of our bear market ailments.

Fooled by randomness and confirmation bias. We see information and patterns and believe we have some profound insight. We are particularly subject to information that confirms our own existing ideas. Most of what lies ahead is uncertain and random—an uncomfortable reality.

Making emotionally driven decisions in the heat of these elevated times can often result in costly mistakes. A better approach is to slow down the process and do some careful and systematic evaluation. In many cases, if we are honest, the results will be vague and uncertain. Often the best course of action is to wait and see how things unfold. From a behavioral perspective, we can reframe, reset, and restart.

Reframing in large part can be helped by taking a longer-term perspective and by viewing information in terms of data and probabilities. To put things in perspective, bear markets happen roughly once every six years, while long-term stock returns average around 11% per year, including all the bear markets and recessions.

Resetting revolves largely around letting go of recent and past events. This can be aided by taking stock of current realities to form a new starting point or baseline.

Restarting can be accomplished by focusing on moving forward and formulating a practical plan of action. Reviewing and revising financial plans can be a valuable tool in this process.

We can also take a cue from successful organizations that know that to survive and succeed they must accept the new realities, develop new plans, and forge ahead.

Putting current events in a longer-term context and focusing on what you can control with practical planning can help relieve stress and avoid costly mistakes. Financial advisors can play a valuable role in helping clients become more aware of potential biases and how to mitigate them.

We believe in an approach for building long-horizon wealth that helps clients deal with the strong emotions associated with unrealized portfolio losses, while avoiding the common biases described above. But proactive advising and coaching do not work for everyone. Using a risk-managed portfolio strategy is a valid approach to “keeping clients in their seats,” essential for building as much wealth as possible.

Numerous strategies are available from investment managers for managing the large drawdown risk associated with bear markets. Of course, it is very difficult to time the market, so it is important to examine the historical and verified performance of each manager’s strategic offerings. These approaches may reduce the pain of drawdowns, but they could also lead to somewhat lower returns in roaring bull markets. For many, this is a reasonable trade-off through the course of full market cycles, with the benefit of creating a smoother ride for investors.

C. Thomas Howard, Ph.D., is the founder, CEO, and chief investment officer at AthenaInvest Inc. Dr. Howard is a professor emeritus in the Reiman School of Finance, Daniels College of Business at the University of Denver. Dr. Howard is the author of the book “Behavioral Portfolio Management” and co-author of “Return of the Active Manager.” AthenaInvest applies behavioral finance principles to investment management and also provides advisor coaching and educational resources.

C. Thomas Howard, Ph.D., is the founder, CEO, and chief investment officer at AthenaInvest Inc. Dr. Howard is a professor emeritus in the Reiman School of Finance, Daniels College of Business at the University of Denver. Dr. Howard is the author of the book “Behavioral Portfolio Management” and co-author of “Return of the Active Manager.” AthenaInvest applies behavioral finance principles to investment management and also provides advisor coaching and educational resources.