Why ‘timing’ is critical for investment returns

Why ‘timing’ is critical for investment returns

There are many reasons that dynamic, risk-managed strategies can benefit investors of all ages. The impact of sequence of returns for retirees is one of the more important ones.

“What if? A probability-based approach to market uncertainty,” a recent article in Proactive Advisor Magazine, is one of my favorites on investment theory for client portfolios. I urge you to check it out if you have not already.

This article talks about the wisdom of constructing a well-diversified portfolio that consists of several different dynamically risk-managed strategies. It also explores the concept of “core” and “satellite” strategies.

The rationale given in “What if?” for this approach is powerful:

“The core should be dynamically risk-managed so that when markets change direction and are declining, you do not participate. Instead, during those times, you stand aside. The current vogue of investing in a static or periodically tweaked portfolio of index funds cannot do this. It continues to participate all right … even to the downside. …

“[Do] not place too few eggs in your portfolio basket. You need to invest in a large number of strategies to reflect the different types of market environments that are always possible.

“You may not know which market environment will occur next, but you do know that one different from the present one will occur. Only a diversified, dynamic, risk-managed portfolio can be better positioned and respond when those changes occur.”

The truly operative phrase here, I think, is “dynamic, risk-managed strategies.”

Why is that so important for clients?

For me, and many of the financial advisors I have interviewed for Proactive Advisor Magazine, it comes down to the concept of “the sequence of returns.”

Over the history of the U.S. stock market, given a long enough period of time, equity investors have been rewarded with growth in their portfolios. However, they have obviously faced periods of extreme volatility and steep drawdowns for those same portfolios.

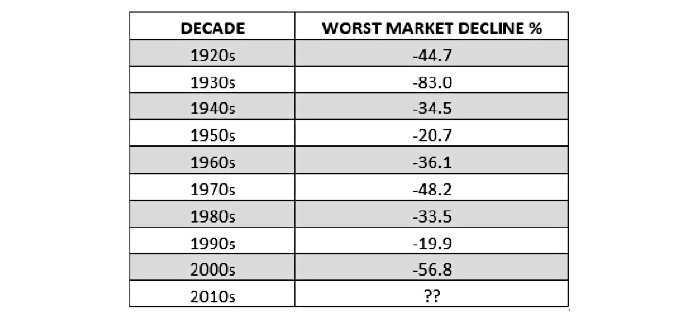

According to data from Yardeni Research, every decade since 1920, with the exception of the 1990s, has had at least one market decline over 20%. Most of those declines were much worse.

TABLE 1: WORST MARKET DECLINES BY DECADE (1920S–PRESENT)

Source: Yardeni Research, market data. Declines measured from peak to trough of correction period.

When significant portfolio losses occur for any given investor is really at the heart of the theory for the sequence of returns. Someone age 25, with 35–40 years of earning and saving years in front of them (the argument goes), can afford to “ride out” stock bear markets. This assumes they never sell out at or near the bottom, as so many people do, nor make significant withdrawals from their portfolios

However, for someone about to enter retirement and begin the distribution phase of their nest egg, as opposed to accumulation, a 25%–50% hit to their retirement funds early on will wreak havoc on their planned withdrawal rates. There is a good chance their funds will no longer last throughout a lengthy retirement.

The article “Retirees’ oncoming financial tsunami” further elaborates on this concept:

“The order in which good and bad years occur during the distribution stage of a portfolio has a tremendous impact on how long assets will last. Sequence-of-returns risk is greatest during the first five to 10 years of retirement. Portfolio balances are at their highest levels, resulting in the greatest absolute dollar losses if the market declines. The need to make withdrawals to meet living expenses compounds the loss. Unless the market rebounds rapidly, there isn’t enough time to recover and portfolios can be depleted long before original projections.”

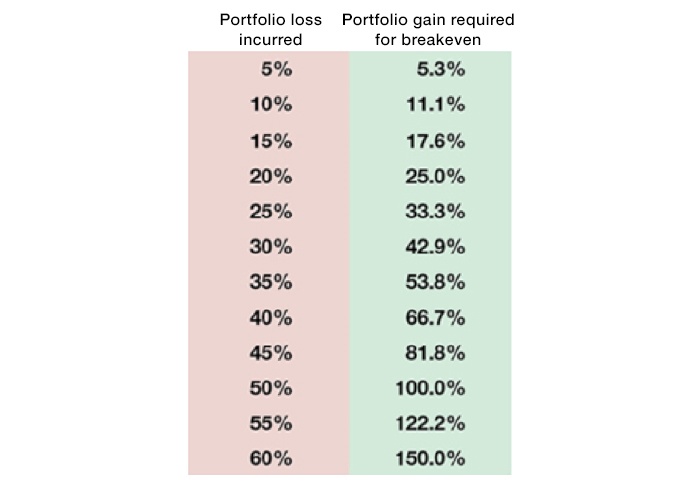

Additionally, the mathematics of bear market losses makes portfolio recovery difficult, as it takes a gain of 50% to overcome a 33% portfolio loss—and a 100% gain to overcome a 50% loss. As losses increase, the percentage gains needed to attain breakeven accelerate at a faster rate.

TABLE 2: BEAR MARKET MATH—REGAINING PORTFOLIO LOSSES

Source: FPI Research

I believe the concept of the sequence of returns started to gain some traction in the financial-planning and investment community in the early 2000s. Consider individuals and couples who had experienced significant portfolio growth in the great equity bull market of the late 1980s and 1990s and were planning on retiring in the year 2000. They were immediately faced with three consecutive years of losses with a combined negative return of about 43% on the S&P 500. (The compounded “math” of bear market losses shown in Table 2 makes the impact even worse.)

To greatly simplify the idea, imagine these people planned to retire with an investment portfolio of $1,000,000 available to help fund their retirement withdrawals for the next 30 years. If they gained 40% in the first years of retirement, their $1.4 million would surely go a lot farther than the $600,000 they actually ended up with at the end of 2002, less withdrawals! While it is unlikely anyone was 100% invested in stocks, the concept still holds true.

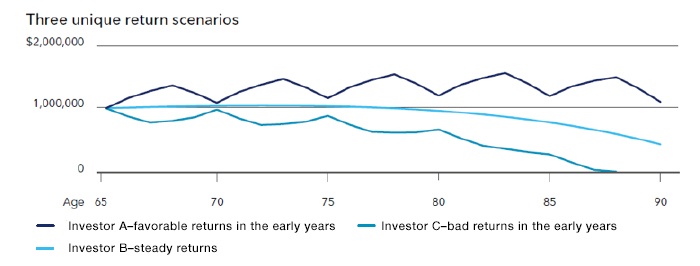

Many investment firms and insurance companies have published their own versions of how the sequence of returns works. One of the largest mutual fund and ETF providers, BlackRock, describes it this way:

- “Three investors made the same initial hypothetical investment of $1,000,000 upon retirement at age 65.

- “All had an average annual return of 7% over 25 years, but each had a different sequence of returns.

- “All made annual withdrawals of $60,000, adjusted annually for inflation.

- “At age 90, all had different portfolio values due to annual withdrawals.”

FIGURE 1: THREE UNIQUE RETURN SCENARIOS

Source: BlackRock

This example of the sequence of returns makes a strong case for dynamic, risk-managed strategies that can mitigate the worst of bear market losses, especially for retirees or those on the cusp of retirement.

We explored this issue in some detail in Proactive Advisor Magazine. Please see “Can lower returns lead to more money in retirement?”

This article, written by a third-party investment-strategy consultant, finds that less-volatile, better risk-adjusted returns (as opposed to “average annual returns”) can result in “significantly more money in retirees’ pockets” over a lengthy time frame.

But what about those who are not close to or in retirement? I think the industry often ignores the sequence-of-returns issue for other investors. What about a couple in their 30s with young children who are planning on their first home purchase? How about a couple in their early 50s who are about to see children go off to college? If their savings/investments are exposed without risk management to the whims of the market, the same principles are in effect—the timing of investment returns can devastate their plans.

There are many reasons that dynamic, risk-managed strategies can benefit investors of all ages. I think the sequence of returns is one of the more important ones.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Proactive Advisor Magazine. These opinions are presented for educational purposes only.

David Wismer is editor of Proactive Advisor Magazine. Mr. Wismer has deep experience in the communications field and content/editorial development. He has worked across many financial-services categories, including asset management, banking, insurance, financial media, exchange-traded products, and wealth management.

David Wismer is editor of Proactive Advisor Magazine. Mr. Wismer has deep experience in the communications field and content/editorial development. He has worked across many financial-services categories, including asset management, banking, insurance, financial media, exchange-traded products, and wealth management.

Recent Posts: