People make this incorrect assumption because they think futures prices are predicting something. That’s not the case most of the time. Just because the current May $VIX futures contract is trading at 16.60, and the September (2016) $VIX futures are priced at 20.15, it doesn’t mean that futures traders are predicting that $VIX will be 20 by September. But once one makes that incorrect assumption, then the conclusion is that $VIX is going to be higher by September. Thus, the argument goes, stock prices are going to be lower (since they generally move in the opposite direction of $VIX).

These statements are far from the truth. An upward-sloping term structure is a natural byproduct of a bullish market, and that’s all there is to it. What makes the term structure slope upward? It is easily explainable. We all know where short-term volatility is—all we have to do is look at $VIX or the near-term futures, or look at the implied volatility of the near-term $SPX options (which is what $VIX is calculated from). Since we’re in a bullish market phase right now, volatility is relatively low, and thus these short-term volatility measures are reflecting a low volatility in the neighborhood of 13–16%. That’s one near-term data point.

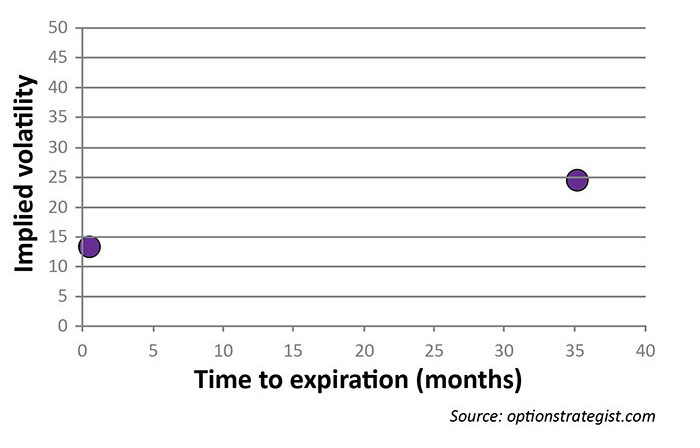

But what if someone asked a market maker to make a market in a three-year $SPX or SPY option? What volatility would be appropriate? No one knows where volatility is going to be in three years, so the market maker would normally just use the “average” volatility of $SPX. On average, the implied volatility of $SPX options is in the low to mid 20s. So now we have two data points. (See Figure 1.)

FIGURE 1

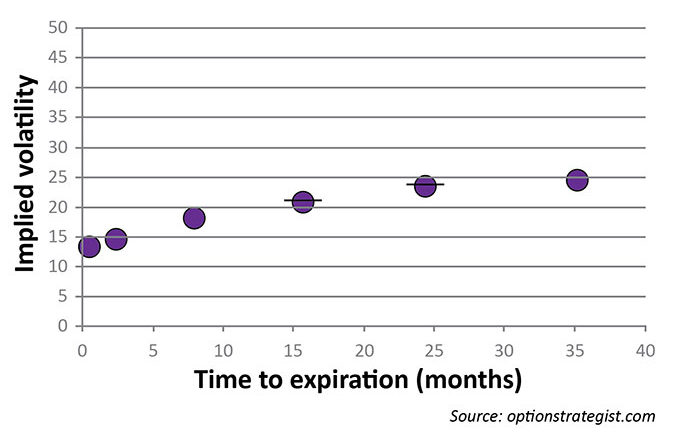

For the pricing of other options along the time spectrum, we can say that their implied volatility would follow a logical path. If it’s a short-term option—say two months—then it’s going to be close to the near-term implied volatility. But since there is some additional uncertainty about pricing a two-month option as opposed to a one-month one, we’d have to allow for some return to the “average” volatility. Thus the two-month option is going to be a tad more expensive (in terms of implied volatility) than the one-month option. Again, this is within the context of an ongoing bullish, low-volatility phase in the stock market.

In a similar manner, if one were asked to price a two-year option, there is a great deal of uncertainty, so one would price it very nearly at the same volatility as the three-year option—near the average, longer-term volatility of $SPX. This gives us two more data points.

Finally, by inductive reasoning, we can estimate where a six-month option and a one-year option would be priced. (See Figure 2.) Note the upward slope of the data points. That’s why the term structure of the $VIX futures slopes upward in a bullish market. It has nothing to do with futures traders trying to predict an increase in volatility over the coming months.

FIGURE 2

In fact, one of the best trades of all time has been to short that longer-term volatility (and probably hedge yourself somehow), because as time passes, and the data points move to the left, they are continually dropping. We call this “The Big (Volatility) Short.” Our firm often has a trading position along these lines.

Eventually the stock market will top and begin to fall, and then volatility will increase. So, yes, at that specific time, the longer-term futures might have actually been a good predictor of volatility. But that’s just a coincidence; it’s not predicting anything. It’s like saying a broken clock is right twice per day.

The term structure also slopes downward in a bear market for similar reasons. In a bear market, near-term options are very overpriced, and thus near-term volatility is high, while longer-term volatility (three-year) is still in the same place. So if one fills in the other data points, the term structure will slope downward in a bear market.

So now you know why the $VIX futures term structure slopes upward in a bull market. The next time you see an “expert” on TV or in print saying that longer-term $VIX futures are predicting an increase in volatility (because they are priced higher than near-term futures), you’ll know better.

Professional trader Lawrence G. McMillan is perhaps best known as the author of “Options as a Strategic Investment,” the best-selling work on stock and index options strategies, which has sold over 350,000 copies. An active trader of his own account, he also manages option-oriented accounts for clients. As president of McMillan Analysis Corporation, he edits and does research for the firm’s newsletter publications. optionstrategist.com

Professional trader Lawrence G. McMillan is perhaps best known as the author of “Options as a Strategic Investment,” the best-selling work on stock and index options strategies, which has sold over 350,000 copies. An active trader of his own account, he also manages option-oriented accounts for clients. As president of McMillan Analysis Corporation, he edits and does research for the firm’s newsletter publications. optionstrategist.com