Why in the world would the Federal Open Market Committee (FOMC) like a weaker dollar?

When the U.S. dollar is strong, imports cost less. This puts pressure on domestic companies whose products compete with cheaper imports. U.S. companies, unable to raise prices and, in turn, unable to pass along additional costs to buyers, become less profitable. By contrast, a weak dollar does the opposite. It is this chain reaction that explains why the July trade deficit narrowed 11.6% from the previous month. This is good news for U.S. multinationals that are able to sell more products both abroad and at home.

Now here is the part that is perhaps a bit counterintuitive. A deflated U.S. dollar on international markets actually leads to inflation here at home. A weaker dollar translates into a dollar being able to purchase less today than it could yesterday. Think of a new car that could be purchased in 1986 for $14,000 that today costs $40,000. It is this inflationary effect that the FOMC is after and why they have embraced a softening, not a collapsing, U.S. dollar. Trade deficits and surpluses (and inflation and deflation), taken together with the currency pairs that drive their movements, are a game of relativity.

The U.S. dollar reached its high for this year during the first week of January and has retreated significantly since. Now that we understand the influence of the U.S. dollar, the positive effect of this move on earnings and the overall economy in the U.S. makes sense. It is no wonder that this past quarter has seen companies, for the most part, improving their bottom line. The U.S. leads the way globally on raising interest rates. It was this that led to the strong dollar as hordes of fixed-income investors sent dollars to our shores in pursuit of our relatively “high” rates, earned safely with an appropriate hedge in place. Today, we are no longer alone; many foreign governments have stopped lowering interest rates, with some even slowly ratcheting rates higher. In January, the 10-year German bund was negative by more than a half-point; today, it is almost 0.4%. This is a huge move.

FIGURE 1: U.S. DOLLAR (DXY)—PAST 3 YEARS

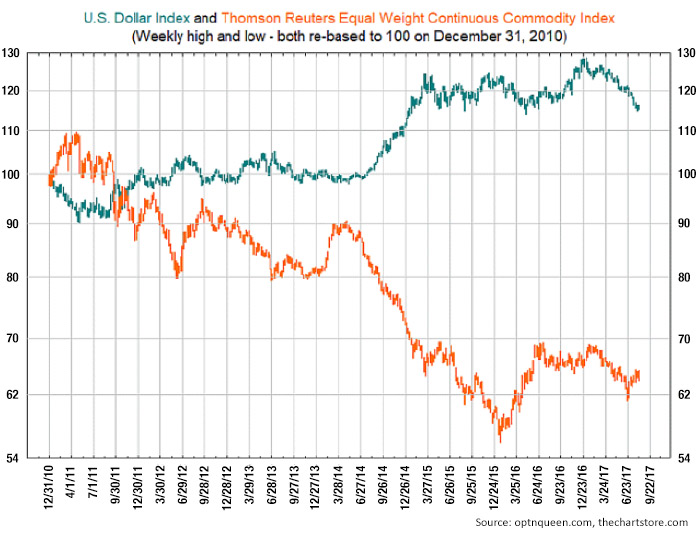

Commodities that trade in U.S. dollars typically go up when the U.S. dollar goes down. When foreign buyers buy commodities traded in U.S. dollars, the relationship is inverse to that of the U.S. dollar. A weaker U.S. dollar gives the foreign currency more buying power because it can purchase more dollar-based commodities.

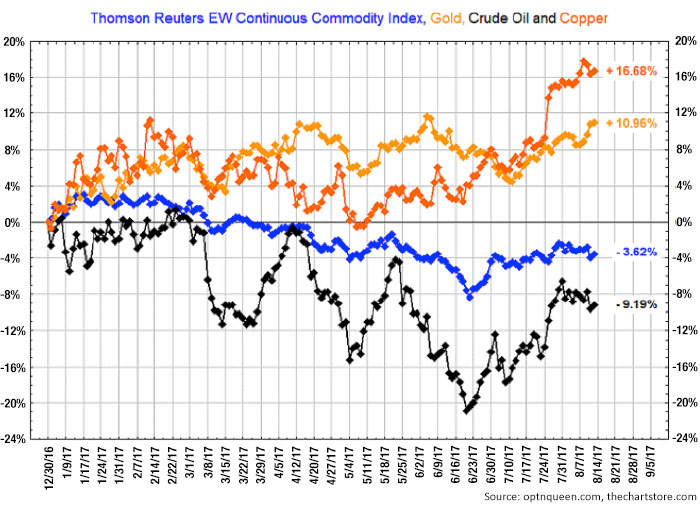

It is this relationship that makes gold and platinum such strong indicators of inflation and dollar movement. When gold and platinum rally at the same time, it is typically the result of a weaker U.S. dollar, with both commodities costing more in dollar terms to purchase. When gold rallies on its own, the metal is acting more like a currency and is not necessarily signaling a deflating U.S. dollar.

FIGURE 2: U.S. DOLLAR INDEX VS. COMMODITY PRICE TRENDS

As a final note, while we never wish for war, threats of armed conflict involving the U.S., by and large, tend to be good for the economy and have consequences for currencies and commodities. A conflict would likely help push us out of the low-inflation, low-growth doldrums that that we have become accustomed to for much of this century. During wars, factories fire up, and employment explodes. Resources are used, and the economy hums along. The U.S. dollar appreciates during unstable times because it is thought of as a safe currency. Gold also rises because it acts as a safe currency, something we have seen most recently during the heightened tensions between North Korea and the Trump administration. (Editor’s note: On Aug. 18, the price of gold broke through $1,300 per troy ounce on an intraday basis.)

FIGURE 3: 2017 YTD PERCENTAGE CHANGE FOR SELECT COMMODITIES/BROAD INDEX

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Proactive Advisor Magazine. These opinions are presented for educational purposes only.

Jeanette Schwarz Young, CFP, CMT, CFTe, is the author of the Option Queen Letter, a weekly newsletter issued and published every Sunday, and "The Options Doctor," published by John Wiley & Son in 2007. She was the first director of the CMT program for the CMT Association (formerly Market Technicians Association) and is currently a board member and the vice president of the Americas for the International Federation of Technical Analysts (IFTA). www.optnqueen.com

Jeanette Schwarz Young, CFP, CMT, CFTe, is the author of the Option Queen Letter, a weekly newsletter issued and published every Sunday, and "The Options Doctor," published by John Wiley & Son in 2007. She was the first director of the CMT program for the CMT Association (formerly Market Technicians Association) and is currently a board member and the vice president of the Americas for the International Federation of Technical Analysts (IFTA). www.optnqueen.com