Investing lessons from an ‘unsuccessful’ wall

Investing lessons from an ‘unsuccessful’ wall

When the line between two types of market corrections is crossed, and the correction turns into a bear market, do your clients really want to have just one investment strategy with which to protect themselves?

I was reading some history recently that focused on the Second World War. It contradicted a long-held belief. I’d always heard that the Maginot Line was a colossal failure.

The Maginot Line was built by the French from 1929 to the end of the 1930s at a cost of 3.3 billion francs. It was promoted as an impregnable fortification that stretched the entire length of the border between France and Germany. Its sole purpose was to protect the French from the horrors they had experienced in the First World War after the invasion from their neighbors to the East.

According to Military History Now, “its 142 bunkers, 352 casemates and 5,000 blockhouses were built using 1.5 million cubic meters of concrete and 150,000 tons of steel. …” The many-miles-thick French “wall” consisted of pillboxes, forts, underground barracks, and the latest in modern and devious defensive technology. It even included an elaborate underground subway system to rush troops to whichever part of the battlefield needed reinforcements.

It was the ultimate in defensive preparedness. It was a “marvel.” It was impenetrable!

On May 10, 1940, the Germans invaded the Netherlands on their way to Belgium and then France, thereby flanking the wall. On June 10, German panzer divisions were in Paris. One week later, the French had surrendered. The vaunted Maginot Line had failed.

At least that’s what conventional history tells us, but was it so?

Historians have dug deeper into the documents of the time. They’ve discovered information that was not generally available when the world judged that the Maginot Line was a failure.

Historians have dug deeper into the documents of the time. They’ve discovered information that was not generally available when the world judged that the Maginot Line was a failure.

It turns out that the French generals actually had a successful plan. The purpose of the Maginot Line was to deter Germany from attacking across the common border with France as they had in the First World War. Instead, it would force them into attacking through Belgium, creating a narrow choke point where the French could more easily stop them.

This aim was accomplished. That’s precisely what the German army did. And the Maginot Line proved to be impenetrable. It never fell until France itself ordered the forts of the Maginot Line to surrender.

If not with their wall, where’d the French generals go wrong? When the war started, they had about the same number of tanks as the Germans had in their invading force. How did the Germans overwhelm the French army when they marched right into the trap the French had constructed for them?

As is so often the case, the French were fighting the last war. They had learned its lessons but had not adapted to the new mechanical capabilities of modern warfare and changed their tactics accordingly.

The Germans launched their offensive with superior air power and their new blitzkrieg methodology of active management of the battlefield. The French mechanized strategy was instead based on placing their tanks in fixed or static defensive positions. The German Luftwaffe and lightning panzer attacks quickly overwhelmed them.

In today’s world of portfolio management, many financial advisors have built themselves a wall. That wall is constructed with static asset allocations based on technology from the 1950s and ‘60s.

That wall, like the Maginot Line, can be successful too. It relies solely on the solid concept of diversification, but it forms just one part of a successful portfolio defense.

To understand why, let’s look at the enemy we are trying to defend against—market declines that are usually shallow, but at times overwhelming.

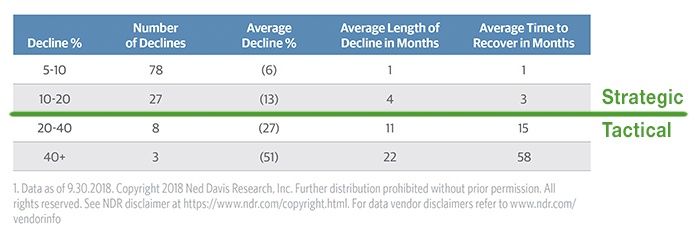

TABLE 1: THE DEEPER THE STOCK MARKET DECLINE, THE LONGER THE RECOVERY

Sources: ndr.com, Guggenheim. Reprinted with permission from Guggenheim’s

“Putting Pullbacks in Perspective,” Critical Conversations series.

Earlier this year, I made my annual trip to serve on Guggenheim’s Rydex Funds Advisory Board. One of the exhibits they displayed was Table 1, which shows the four types of stock market declines since the Second World War. The implications for portfolio construction were immediately apparent.

The first two categories encompassed declines of 5%–20%. They were numerous, shallow, and the recoveries were swift. The last two groupings of 20%-plus–40%-plus were rarer, very severe, and required a great deal of time just to get back to breakeven.

If one draws a line under the first two categories, the demarcation of the four categories into two groups is stark. It’s not surprising that each group requires a different strategy.

The top two categories can be successfully dealt with by the static asset-allocation portfolios that have become a dime-a-dozen commodity in the financial world. Because the drawdowns are lower and the recovery time short, a strategically diversified portfolio, like the Maginot Line, can provide an adequate defense. The diversification does its job, mitigates the quick declines, and stays invested for the short recovery.

However, to combat the more aggressive attack presented in the last two categories—which can cause severe declines and require a long time to recover—a different defensive approach is needed. During these deep declines, the asset classes of a simple, diversified portfolio all fall in unison, usually by at least as much as the S&P 500. Only a tactical move to bonds, gold, and/or cash has historically proven truly defensive.

As the French learned to their sorrow in WWII, an active defense rather than a static one is essential. This is where tactical investing becomes a necessary component part of a portfolio.

Investors can sit through a short, shallow bout with an attacking “baby bear market,” but few have been able to deal with the relentlessness of a “full-grown bear market,” the type the last two categories detail. Few can stay true to an investment portfolio that is underwater for almost five years!

We have had two stock market declines of more than 50% since the 2000s began, and in the case of tech stocks, the declines have been over 70%.

Ask yourself, can your clients (and you) withstand another 50%-plus stock market blowout? Can you afford to put at risk all of the gains earned in the current “super bull market”?

Flexible Plan’s dynamic risk-management strategies did a good job of navigating through the “baby bear” pullbacks in 2018.

I looked at one of our robust suites of actively managed strategies (Strategic Solutions) and the majority outperformed the S&P 500 Index (SPX) during three different time periods in 2018, all with an end date of the 2018 market low on Dec. 24. During one period when the market moved from a cycle top to a bottom—from Sept. 20, 2018, through Dec. 24, 2018—87% of Strategic Solutions strategies performed better than SPX (including accounting for management fees).

However, the next pullback may be “the big one,” taking investors below the line separating the two pullback groupings in Table 1.

At the Advisory Board meeting, Guggenheim demonstrated their Recession Indicator model. It has a great record of predicting recessions.

Recessions are the time when 50%-plus declines in the market are most likely to occur. Currently, their indicator is pointing to the summer of 2020 for the inception of the next recession and suggesting that a decline greater than 45% in stocks is likely this time around. They also point out that due to the relatively low level of interest rates, Fed policymakers may have a “limited scope for policy response once the recession hits.”

Before you panic, realize that this outlook, like anything, can be wrong. And the stock market has made a strong move higher in 2019. Getting out now based on a projection over a year in the future is probably not prudent.

But I do suggest action. I would advise that if you have not already included dynamic risk management in your clients’ portfolios, now is the time to match their passive, strategically allocated core 50%–50% with a tactical core.

A tactical core not only supplies the strategic diversification of asset classes, but it also has the capability of the German blitzkrieg to swiftly change position. In dealing with the impending menace, it can respond. It can become neutral like Switzerland, reactive like Great Britain, or proactive like the United States was in WWII—whatever is demanded of it.

Over the years, we have found that, like the French sole reliance on the Maginot Line, a single strategy is not sufficient to deal with modern threats. That’s why we cannot rely, like so many financial advisors do, on a single strategic allocation portfolio for our clients’ defense.

Instead, we have always advocated a multi-strategy portfolio that combines the best of both a diversified portfolio and tactical, dynamic risk management. A multi-strategy approach can work well for a multitude of suitability profiles.

A new combination of our most popular core strategies, in addition to being able to form the basis for a portfolio of dynamic risk-managed strategies, was primarily designed to be paired with a traditional, passive core portfolio. Its goal is to provide investors that, until now, have only had a single, Maginot Line–type of protection, with a multi-prong defense for when the bear outflanks them and only an active defense will do.

When the line between the two types of market corrections is crossed, and the correction turns into a bear market, do your clients really want to have just one investment strategy with which to protect themselves?

Jerry C. Wagner, founder and president of Flexible Plan Investments, Ltd. (FPI), is a leader in the active investment management industry. Since 1981, FPI has focused on preserving and growing capital through a robust active investment approach combined with risk management. FPI is a turnkey asset management program (TAMP), which means advisors can access and combine many risk-managed strategies within a single account. FPI's fee-based separately managed accounts can provide diversified portfolios of actively managed strategies within equity, debt, and alternative asset classes on an array of different platforms. flexibleplan.com

Jerry C. Wagner, founder and president of Flexible Plan Investments, Ltd. (FPI), is a leader in the active investment management industry. Since 1981, FPI has focused on preserving and growing capital through a robust active investment approach combined with risk management. FPI is a turnkey asset management program (TAMP), which means advisors can access and combine many risk-managed strategies within a single account. FPI's fee-based separately managed accounts can provide diversified portfolios of actively managed strategies within equity, debt, and alternative asset classes on an array of different platforms. flexibleplan.com