Is the market’s lofty valuation justified in the middle of a pandemic?

Is the market’s lofty valuation justified in the middle of a pandemic?

Managers can’t expect to make rational decisions about the risks and opportunities of individual stocks, sectors, or indexes without considering the overall market and economic environment. Current market fundamentals don’t explain the whole story—behavioral insights can provide valuable context.

There’s no playbook anywhere that can offer a lesson as to what to do in the markets right now.

As of the writing of this article, it is four months from the March 23 low in the markets and the COVID-19 story is far from over. Whole industries have come to a standstill and unemployment rivals that of the Great Depression. The federal government is writing checks to citizens and throwing trillions in aid to businesses. While some sectors have been clear winners in this new environment, fixtures of the American business landscape are lining up to go bankrupt while others struggle to meet unexpected demand.

The market sold off precipitously for five weeks as the crisis unfolded, but then turned on a dime and recovered the majority of that loss, bringing the market’s overall valuation to extremes rarely seen even in the best of times.

What gives? How can we put something in perspective that never happened before? And what might we expect from here?

Trying to force fit the current environment into the same bucket as prior market sell-offs of this magnitude is futile and can be grossly misleading. This is clearly not 2008, 2000, or 1987. A look at the current market valuation illustrates the point.

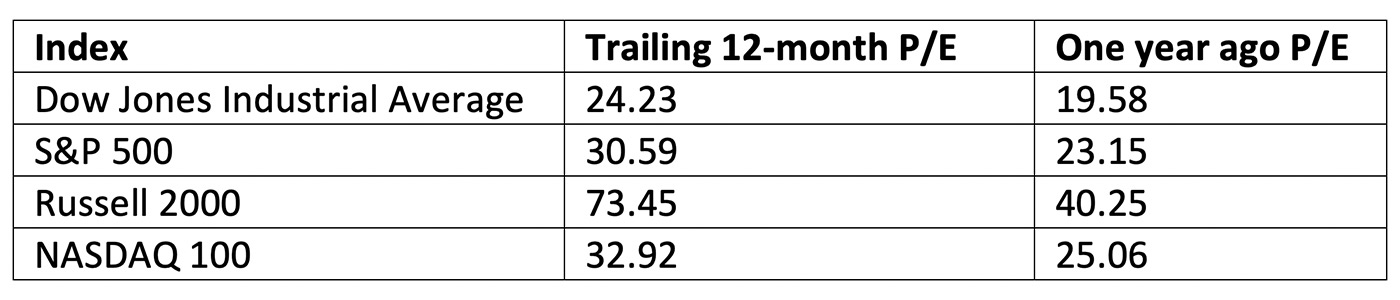

While bullish commentators defend current market valuations as being well below the levels of previous so-called bubbles, such as those in 2000 or 2008, there is no denying that valuations are currently rich by historic measures. Table 1 shows the price-earnings (P/E) ratios of major indexes as of July 24–28.

Note: Dow Jones Industrial Average as of 7/28/2020. Other indexes as of 7/24/2020.

Sources: Barron’s, Birinyi Associates, Dow Jones market data

CurrentMarketValuation.com tracks four valuation indicators continually. As of July 28, two of these were rated as “Overvalued” (S&P 500 P/E Ratio Model and S&P 500 Mean Regression Model) and two were “Strongly Overvalued” (Yield Curve Model and Buffett Indicator Model: a ratio of total U.S. stock market valuation to GDP).

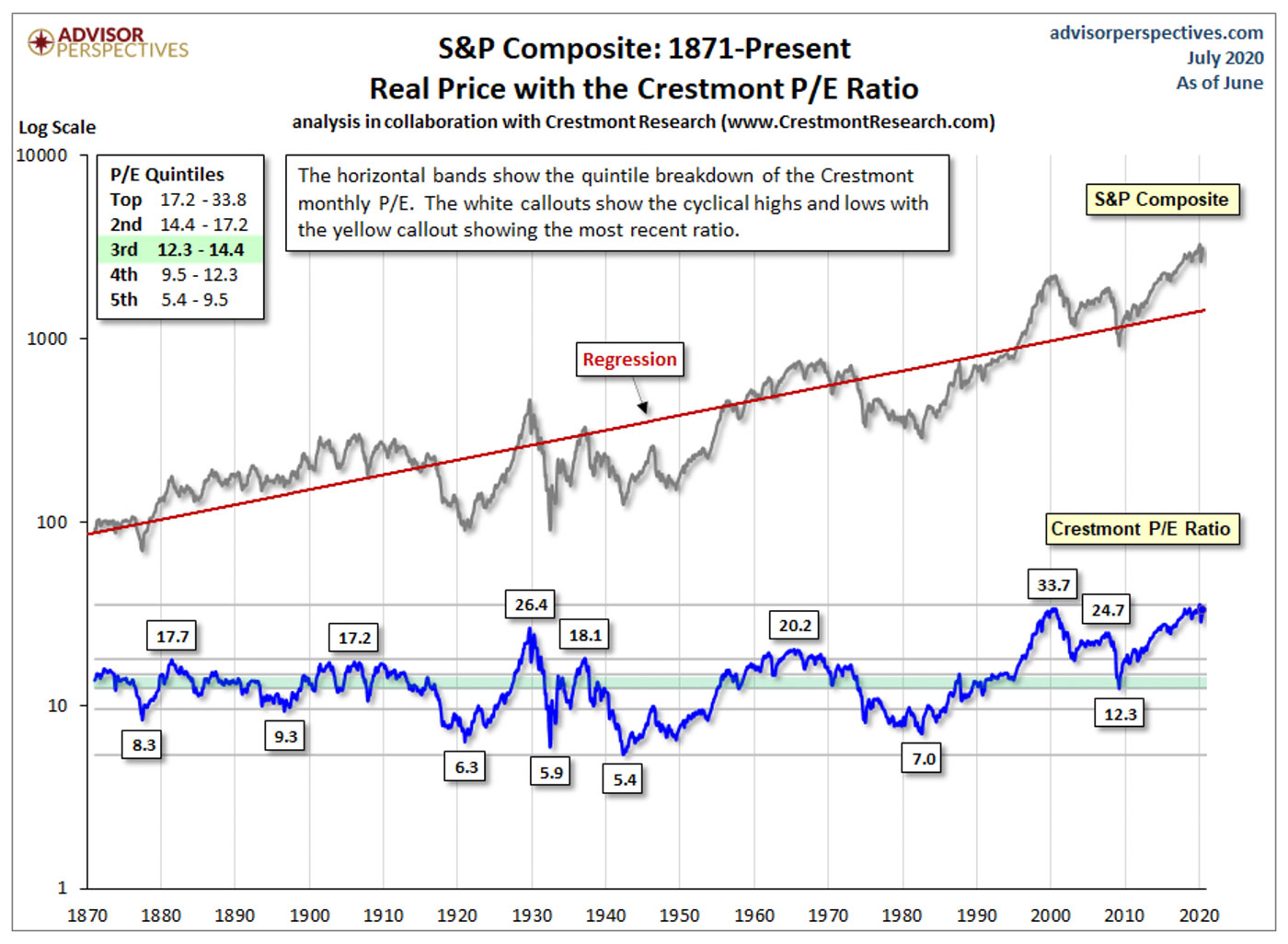

A long-term view (updated quarterly) from Crestmont Research and published at Advisor Perspectives, indicates that as of June 30, 2020, “The Crestmont P/E of 33 is 119% above its average (arithmetic mean) and at the 99th percentile of this fourteen-plus-decade series.” In other words, it is in the top 1% of valuations for the last 140 years, as can be seen in Figure 1.

Sources: Crestmont Research, Advisor Perspectives, as of Q2 2020

Such valuations can make managers squirm as they are often felt to foretell, at best, a diminished view of returns for the foreseeable future and, at worst, another possible near-term cliff from which the market may tumble. But while analysts and investors can point to both such scenarios in history, there is not sufficient data support for statistical confidence in determining a future outcome.

Furthermore, they aren’t the only scenarios we’ve experienced. A glance back at the Crestmont chart shows that the market hovered at valuations that were near the upper extremes during the entire decade of the 1960s. Then, in the 1980s, the markets took off with a vengeance until 2000, by which time the market’s overall valuation had catapulted to a new high that was 166% higher than the prior valuation peak in the mid-1960s. (That was also, by the way, three years after former Federal Reserve Chairman Alan Greenspan uttered his famous “irrational exuberance” warning.)

The reality of valuation multiples is that they may, at times, reflect a lot more about our collective mindset than the underlying fundamentals and that they are far more elastic than most people might think.

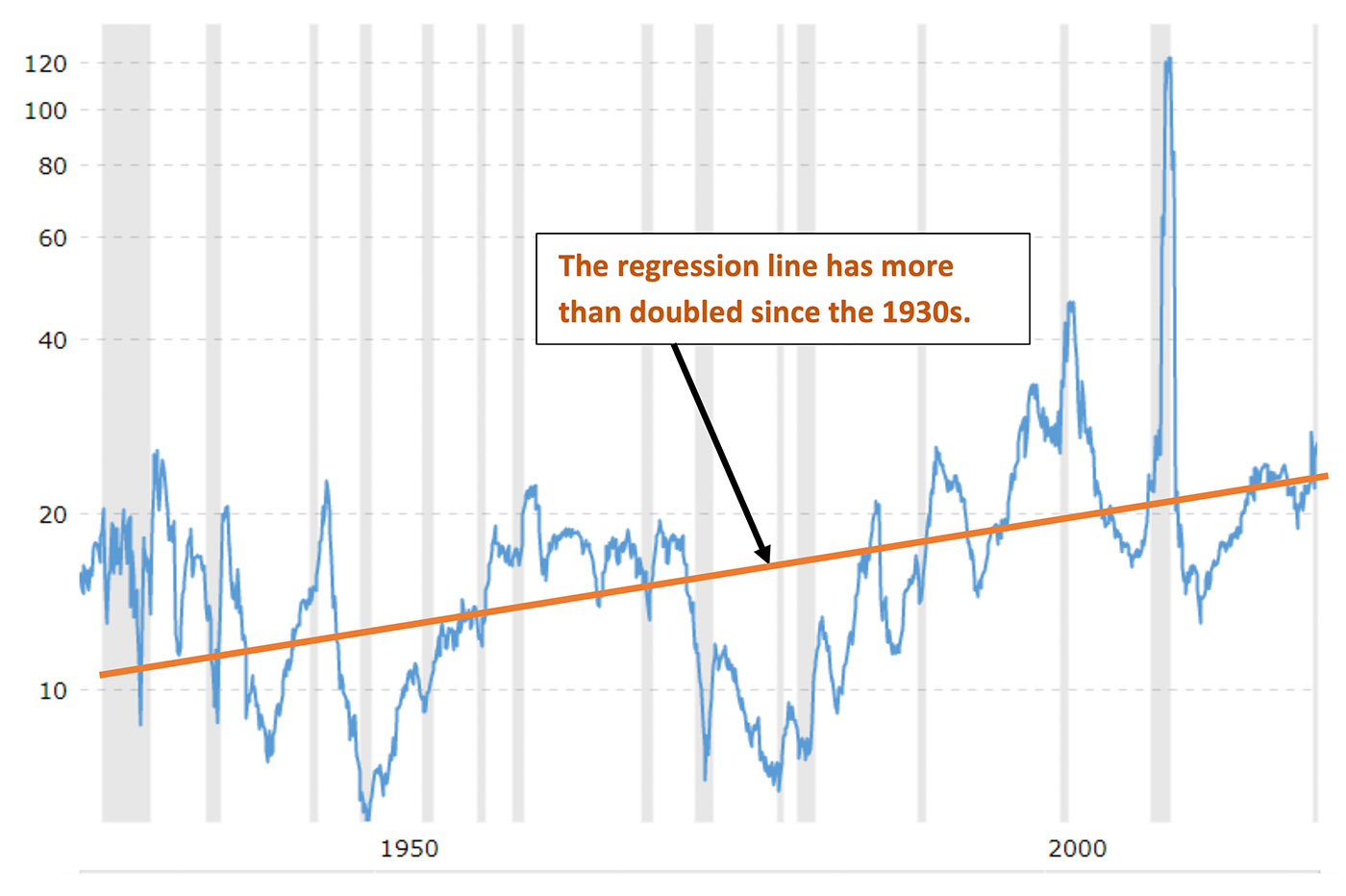

What’s more, the assumption that market P/E ratios are bound by the horizontal data range of the past 100 years is naïve, especially when viewing only annual values of the multiple. A look at P/E ratios for the S&P 500 by month reveals even more striking extremes.

Source: Macrotrends

What’s more, a standard regression line through P/E ratios over the last 90 years (Figure 2) shows that they have not been flat over time but have been decisively rising. The mean monthly P/E ratio from a regression line in the chart in Figure 2 has more than doubled since the 1930s, and the trend steepened even more during the last 50 years. No matter how you choose to justify it, the market has been increasing its valuation multiples over time as well as exhibiting peak multiples at extreme new heights.

Many fundamental explanations exist for why valuations should be elevated right now.

The first and most evident is that valuations based on trailing, rather than expected future earnings, will always become exaggerated during steep short-term drops in earnings. Beyond that, there is the supply and demand argument about too much money chasing too few stocks, aided by a large and steady stream of pension and 401(k) money that flows automatically into stocks every month. Then there is the improved productivity argument and the fact that large growth stocks with sky-high P/E ratios now occupy a higher proportion of the S&P 500 Index than ever before. Let’s not forget substantially lower corporate tax rates, record low interest rates, extremely low inflation, and an unequivocally business-friendly administration.

All of these factors have merit. But they don’t change the fact that valuation is highly subjective.

The initial move in mid-February took five weeks to drop approximately 38%. At that time, we were all still trying to figure out what we were dealing with and how much of it was a health problem versus an economic one. Since we have never really seen a crisis that included wholesale shutdowns of schools and businesses, and since the story was a gradually evolving one, five weeks is certainly understandable. Remember, in 1987, there was no health crisis at all (or any other notable crisis, for that matter), and it took just two days for the market to fall as much as it did in the COVID drop.

This is where the behavioral factors start to come in.

At present, people all over the world are concerned, to put it mildly, about going to work, socializing, visiting their parents, or sending their children to school. Many have no work to go to. Families have been forced into a new normal of constricted behavior. The notion that everyone can turn all of that emotional stress off, sit calmly down at their computers or the kitchen table, and make rational financial decisions is highly suspect. There is little question that the collective anxiety in the population is being reflected in the markets, and the impact of crowd psyche on the markets isn’t always intuitive.

First, we know that investors will discount both stocks and the market for uncertainty (certainty or ambiguity bias). The initial monthlong drop in the market from late February into late March undoubtedly represents the onset of uncertainty surrounding the virus and the closing of businesses around the country. Selling tends to beget selling (herding bias), at least among participants who are overleveraged or simply more temperamental (loss aversion).

In addition, the markets had been enjoying one of the longest bull markets in history, causing at least some investors to want to lock in those gains quickly at the first signs that trend might be ending (disposition effect). Some degree of panic-based selling (fear of the unknown) finally brings the market down to levels where cash-laden investors perceive a low-risk entry point on the buy side (fear of regret or fear of missing out) and a recovery ensues. From a behavioral perspective, this much at least is somewhat intuitive.

What happens from there gets more complicated. One documented phenomenon in stock prices is “underreaction-overreaction.” It posits that investors tend to initially underreact to news events that materially alter the underlying fundamentals on stocks and eventually overreact once everyone is on board. This is a conclusion reached from numerous studies on earnings and news announcements, but one might extrapolate this phenomenon to the overall market as well. That would suggest when the low was reached on March 23, it was likely an overreaction, at least based on the news up until that time, and the nearly 20% bounce-back over the following week would represent the market’s acknowledgment of that overreaction.

Understanding the continuing climb of over 40% from the lows may not be quite as intuitive. No one will have a definitive answer to this, but there are quite a few possible contributing factors:

- Just as selling begets selling, buying does the same. Once a sufficient number of bargain hunters have induced a visible turn and a possible low is in place, the herd steadily begins to re-enter on the upside. Herding, trend following, and momentum are all classic hallmarks of market behavior.

- In general, the public expected the pandemic crisis to pass in a few months and businesses to reopen quickly. Initial estimates had projected reopenings by Easter. Thus, at the time of the low, people were thinking this would all be over in a month or so and the damage manageably contained.

- There was (and remains) a high degree of confidence that the government will come to the aid of businesses at almost any cost.

- Both the media and the current administration exhibited strong optimism bias. Just as the focus in wartime is on the victories, attention in the media was directed to high-profile companies that were not just thriving amid the pandemic but realizing windfall gains. In addition, stories emerged about how even hard-hit companies such as Hertz and Carnival Cruise Line were going to emerge from this crisis intact, reducing the fear of possible bankruptcies.

- In addition, there was the “lottery effect” in pharmaceutical stocks over a potential vaccine and in some tech stocks and other companies that might benefit strongly from the crisis. A possible “halo effect” may well have carried the lottery effect over to the rest of the market (whether justified or not).

- Investors tend to be forgiving about one-time balance-sheet hits, inflicting surprisingly minor damage to stock prices as long as earnings streams remain relatively healthy. This is seen in many situations involving sizable write-offs, legal expenses, or fines.

- Current valuations are reflecting an exceptionally high influence from tech stocks that were already widely popular and are actually benefiting from the current situation. Focus on the tech darlings of our time may be drawing attention away from a broader number of companies who are not faring as well.

- Free trades, low interest rates, and time at home with a computer are encouraging a resurgence of individual investors trading the market, and they almost always trade from the long side. This was long held to be at least partly responsible for previous periods of overvaluation.

- People may have seen the March decline as the best opportunity in years to deploy cash into equities. This might represent a combination of FOMO (fear of missing out) and TINA (“there is no alternative”), given low fixed-income yields and even lower cash-equivalent yields.

- With 11 years of upward prices as their dominant reference point, many see the 2008 drop not as a danger point but as a golden opportunity that was missed by many who were too skeptical at the time to take advantage of it. The fact that COVID handed investors a 38% drop in stock prices was likely to have been viewed by many as the first time in more than a decade to jump on a great long-term buy point. This may have been especially true for investors or institutions who missed a good portion of the bull market move higher starting in 2009.

Valuations may well level out here or even decline, but the emotional forces driving them are likely to keep them from collapsing. Many who sold in the initial COVID decline may already regret that decision and not want to get bitten twice. The initial shock of the pandemic has already been absorbed.

Unless there is new and clearly negative information, it is unlikely we will see another decline as quick and severe as the previous one. People will be looking ahead, and while there is likely to be a second wave of the virus in the fall, as well as a national election, many expect one or more treatments and/or vaccines will emerge (or at least be anticipated), and that will likely serve to keep valuations elevated for a while.

These observations cannot be definitively proven. However, if discretionary investors or investment managers don’t try to understand why the market is behaving as it is, they are far more inclined to emotionalize a response. Each market crash and recovery of the modern era has had its own unique causes and recovery characteristics. Market players are still people first, and, to a large degree, it’s their perceptions, beliefs, and emotions that drive prices.

But this type of market and the valuation conundrum can be a challenging one even for the most sophisticated investment managers following a rules-based regimen. The whole idea of a rules-based approach is to establish a discipline that supplants guesswork and emotional instinct. That obviously becomes more difficult when a new scenario presents itself, market moves and volatility are outsized and fast to both sides, and many historic norms fly out the window.

The more successful rules-based investment managers, based on my observations, understand the importance of adapting to change and new information. While the fundamental methodologies of their strategies may remain largely the same, they apply new information rapidly and use powerful tools to help refine their data-driven rules over time. Given the uncertainties of today’s investment environment, and especially the market’s valuation extremes, that discipline now becomes more important than ever.

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.