Not all investment returns are created equal

Understanding the important differences between absolute return, total return, and relative return.

The financial media has spent quite a bit of time during the current bull market reporting on the “underperformance” of actively managed funds. While the attitude of this reporting has not exactly been gleeful, there has been a definite sense of “I told you so.” “See, you can’t beat the market,” they say, or “It just isn’t possible to be a market-timer.”

A critical flaw with these arguments is that they are usually based on an assessment of how an actively managed mutual fund or ETF is performing against a specific benchmark asset class, sector, index, or proxy index.

These arguments are not based on an evaluation of a holistic approach to dynamic, actively managed portfolios, which are most often not tied to the performance of a benchmark, but intended to provide a competitive range of returns with lower risk exposure over time—while attempting to avoid the portfolio-crushing drawdowns of severe bear markets.

A very important distinction, indeed.

But the viewpoints expressed in the media also raise the issue of how financial advisors and wealth managers (and, importantly, their clients) should be thinking about monitoring portfolio performance and the context for evaluating investment returns over time.

The “human factor” in evaluating investment returns

While most investment and financial professionals don’t necessarily emulate the strategies of private funds, many of the strategies employed in the broad field of active management do share some commonalities with the private-fund investment approach.

However, several important client questions around “performance” are shared between the most sophisticated professionals and everyday investors.

The questions always tend to lean toward a common denominator, human nature being what it is: “Why am I not up as much as the overall market?” Not, for most investors of all stripes, “Why am I not down as much as the overall market?”

Many investors, and the business and financial media, have missed the point altogether.

One important goal of private-fund strategies such as Bridgewater Associates’ “All-Weather” absolute-return approach is to control risk and minimize drawdowns. This can certainly lead to some “underperformance” during strong bull runs in the equity markets, but generally a much smoother upward-sloping line of compounded returns over the long haul.

It is hard to argue with the approach of what is generally considered the world’s largest and most successful private fund, which has delivered an enviable record of positive annualized returns (though the fund has seen years with small absolute losses in its 20-year history). Similar consistent results over time can be found emanating from the strategies of many money managers who focus on active portfolio management, although their strategies and tactics can vary widely.

Advisors, and their client investors, would probably be far better off by avoiding the temptation to mentally compare their portfolio results each week, month, and year to “the market.” This can frequently lead to unnecessary strategy switching, always chasing last year’s “hot strategy” or better-performing sectors or asset classes. It is pretty reasonable to suggest they will be far more satisfied (and be less stressed) in the long run with consistently steady returns that generally stay on the positive side of the ledger, compounding over many years.

What does “return” really mean? (It can mean many things)

There is a high degree of fuzziness that exists in understanding concepts such as absolute return, total return, relative return, and risk-adjusted return.

Alfred Winslow Jones is credited with forming the first “absolute-return” fund in New York in 1949, and the concept gained in popularity in the 1990s and early 2000s as the private-fund industry became more visible and prominent in financial circles. One could argue that the overall premises of absolute return in theory and practice are (1) to ensure the return of capital, and (2) to deliver returns that are consistently positive, although they can often be relatively modest in nature. Some have described early absolute-return strategies as simply having an objective of beating “the holding of cash.”

“Why am I not up as much as the overall market?”

But the objectives for most funds using absolute-return strategies today are far more ambitious, reflecting the fact that many more investment options are available and easily accessible.

Investment tools and strategies include many forms of diversification among asset classes, and can also include using short selling, inverse funds, futures, options, derivatives, arbitrage, leverage, private equity, and many nontraditional asset classes to help ensure more “market-neutral” exposure, leading to the desired positive absolute return.

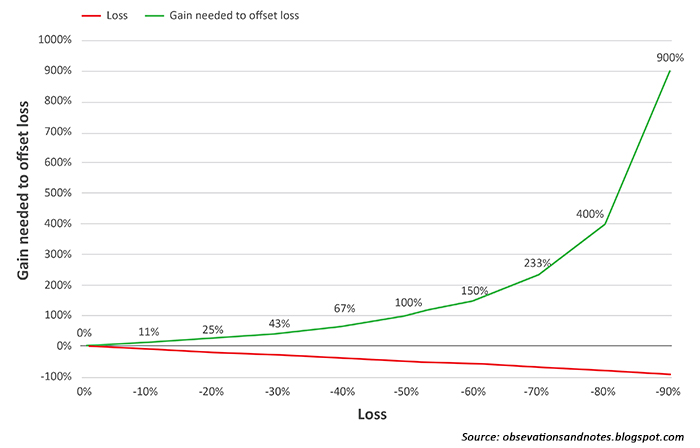

Taking this one step further, absolute return would certainly factor in another concept, total return, including interest earned, capital gains, dividends, and distributions realized over a given period of time. The appeal to the large individual investor or institution is in applying the simple rules of compounding over time, while avoiding large drawdowns during periods of market uncertainty, volatility, and risk to capital. The concept of absolute return realizes at its most basic level that it takes more than a 50% increase in portfolio value to overcome a 35% loss and would rather achieve long-term portfolio growth through smoothing out the peaks and valleys found in virtually all asset classes.

FIGURE 1: GAIN NEEDED TO OFFSET MARKET OR SPECIFIC EQUITY LOSS

Compare this to relative return, where funds of all types compete against each other to beat a designated benchmark, which could be any index under the sun but is most commonly the S&P 500 Index among those looking at equity performance. While relative return has its place in the investing universe, it is probably of most value in evaluating specific tactical choices within an overall investment portfolio framework.

There obviously has been a lack of consistency in performance of the S&P benchmark over the past 20 or so years, with annual total return ranging from a low of −37% (2008) to a high of +38% (1995). While the annualized average S&P return has moved back toward the historical norm with the current bull market, it has nonetheless been an often painful experience for those living through it tick by tick. And it is challenging for many, especially individual investors, to “stay the course.” Many estimate that traditional asset-allocation strategies carry an 85%–90% correlation to the equity markets, with all of the subsequent risk implications.

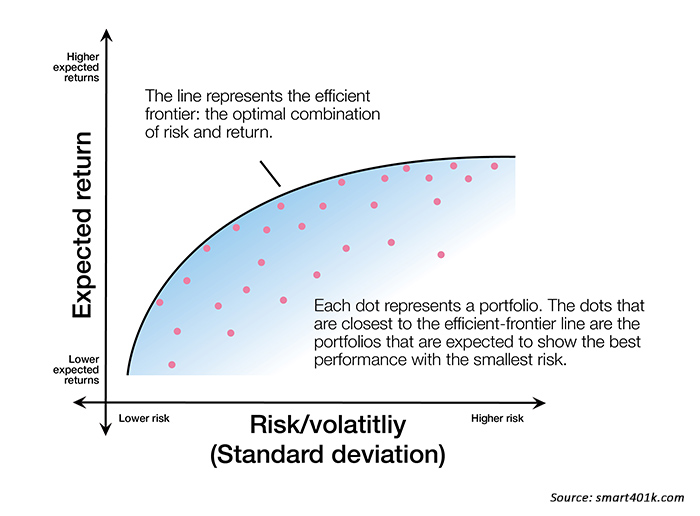

Having reviewed those two measurement “extremes,” let’s look briefly at risk-adjusted return, which fundamentally is an even more sophisticated way of looking at absolute return. Those active managers who endorse the risk-adjusted return school of thought employ any number of risk measurements and probability theory to quantify the exposure of a diversified portfolio approach to losses and drawdowns, while maximizing gains. Using the most advanced backtesting tools, these approaches can quantify such measures as alpha, beta, r-squared, standard deviation, and the Sharpe ratio in identifying optimal portfolio mixes and returns along a risk curve for different time frames and economic conditions.

And like absolute return, the risk-adjusted return approach attempts to achieve a portfolio compounded-growth pattern, which moves from lower left to upper right within a fairly well-defined and rather tight channel. To paraphrase Ray Dalio, founder of Bridgewater, most investors, including large institutions, tend to focus too much on allocating capital rather than the allocation of risk.

Many of the strategic portfolio approaches employed today are founded in modern portfolio theory (MPT) and Harry Markowitz’s concept of the efficient frontier, although applying more advanced analytical tools and attempting to address some of the inherent weaknesses in these theories. (See Proactive Advisor Magazine’s article, “A more efficient (and profitable) frontier.”) But the core thesis of the efficient frontier still provides a valid conceptual framework for thinking about risk-adjusted expected returns: optimizing portfolios at a designated level of risk or identifying portfolio construction for the lowest risk for a desired expected return.

FIGURE 2: CONCEPTUAL FRAMEWORK FOR THE EFFICIENT FRONTIER

The growing use of absolute-return strategies

Most active managers and the advisors who employ their services would probably agree: It is of the utmost importance to deliver strategies to clients that can live within their specific risk profiles and their comfort levels with probabilities on portfolio drawdowns, no matter what the current investment environment.

Following the financial crisis of 2007–2009, a good number of money managers began a quest to develop their own versions of absolute-return strategies. These come in all sizes, shapes, and colors. They might have allocation strategies somewhat similar to Bridgewater’s absolute-return approach, could represent a unique portfolio model of a specific investment manager, or be an important (or even dominating) component of what is commonly known as the endowment investment model. In the latter case, four overall distinguishing features of the endowment model are (1) generally a much lower-than-“normal” allocation to U.S. equities; (2) employment of alternative investment classes such as hedge funds, private equity, venture capital, and real assets such as oil and natural resources; (3) lower overall portfolio liquidity, in some cases requiring much longer time frames for exiting specific investments; and (4) usually a significant level of allocation to absolute-return strategies.

According to Yale University, its endowment fund has consistently been one of the top-performing funds among its peers over the last 20 years, “returning 12.6% per annum.” Going into its next fiscal year, Yale states that it has a 22.5% allocation to absolute-return strategies and only 4% (!) allocated to domestic equities.

While many forms of absolute-return strategies exist, according to investment firm BlackRock they all basically share the same broad objective:

“Absolute return investing aims to produce a positive return over time, regardless of the prevailing market conditions. Even when markets are falling, an absolute return fund still has the potential to make money. …

Unlike a traditional long-only equity fund where investors accept the risk that equity markets can fall dramatically from time to time, an absolute return—by not being tied to any particular equity benchmark—aims to produce more consistent positive returns over a given investment horizon. Investment gains can never be guaranteed but, by using a range of techniques not available to traditional investment portfolios, absolute return funds have the capability to generate smoother returns throughout the market cycle.”

***

The time-honored principle of “past performance does not guarantee future results” holds true with any strategic investment approach, no matter the level of sophisticated tools or backtesting involved (as seen during the 2007–9 credit crisis). All absolute-return strategies, for example, do not always produce a positive annual return. (In fact, the Bridgewater All-Weather fund has suffered single-digit losses in two of the past three years, according to Forbes, although the fund has “produced annualized net returns of 7.7% since its inception in 1996.”)

But it is safe to say that absolute-return strategies have several significant advantages and distinguishing characteristics. In general, they (1) produce fewer losing years than traditional portfolio allocations; (2) seek upside potential with downside protection; (3) have a goal of significantly lowering levels of drawdowns across both short-term and long-term time frames; (4) work to reduce overall portfolio volatility; and (5) are built with an eye to managing exposure to the impact of historical asset-class correlations. Interestingly, as BlackRock points out, “In a traditional 60/40 portfolio, equities may make up about 60% of the total assets, but can generate 96% of the expected risk of the portfolio.”

For today’s investment environment, and for the right clients, absolute-return strategies might be able to play a very significant role in portfolio construction. By definition, they are designed to develop more stable returns no matter the investment environment or the current market regime. And they certainly help to demonstrate why “not all investment returns are created equal.”

Editor’s note: A version of this article first published in Proactive Advisor Magazine on January 9, 2014, Volume 1, Issue 1.

David Wismer is editor of Proactive Advisor Magazine. Mr. Wismer has deep experience in the communications field and content/editorial development. He has worked across many financial-services categories, including asset management, banking, insurance, financial media, exchange-traded products, and wealth management.

David Wismer is editor of Proactive Advisor Magazine. Mr. Wismer has deep experience in the communications field and content/editorial development. He has worked across many financial-services categories, including asset management, banking, insurance, financial media, exchange-traded products, and wealth management.