Behavioral finance applied: Strategies, not style boxes

Behavioral finance applied: Strategies, not style boxes

Applying behavioral finance concepts to fund manager behaviors has proven helpful in selecting top-performing equity funds.

In an earlier Proactive Advisor Magazine article, I presented a framework, based on five concepts, for implementing behavioral finance throughout the advising and investment-management process. The fourth of these five foundational ideas states that alternative behavioral tools can be developed for operating in financial markets.

In this article, I discuss how behavioral tools can be used to select and then evaluate an active equity fund, along with constructing an equity fund portfolio. Like every aspect of investing, these decisions are fraught with emotional triggers and, if not properly handled, often lead to poor performance. Applying behavioral concepts can help financial advisors avoid a number of cognitive errors in the construction and management of such portfolios.

The most popular way to select an active equity fund is by choosing the one with the best recent performance. This seems so intuitive that it is accepted without question by advisors and clients alike, even though every investment product displays the warning that past performance is not indicative of future performance. Academic research confirms the unreliability of past performance as a predictor of future performance.

Despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary, past performance remains the primary criterion used for picking funds. This is an example of the representativeness bias, where decisions are made based on characteristics that have little or no predictive power but are emotionally appealing. And this bias is nowhere stronger than it is in investment markets.

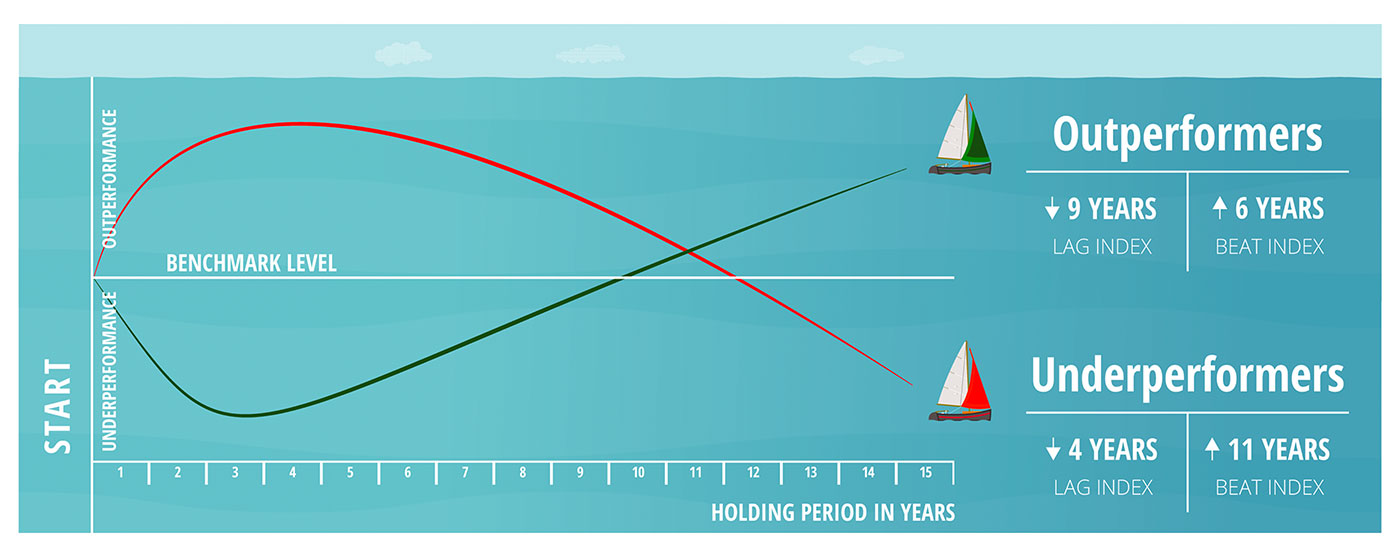

A study by Morningstar’s Paul Kaplan and Maciej Kowara reveals how challenging it is to select an active equity fund based on past performance (see Figure 1). Using a worldwide sample of 5,500 active equity mutual funds, they find two-thirds outperform their benchmarks, gross of fees, over the 15 years from 2003 through 2017. But the most surprising result was that the typical outperforming fund underperformed, on a cumulative basis, for a period of nine to 12 years within this 15-year sample period. This means that the outperformance takes place in only three to six years out of a 15-year holding period!

They found mirror results for the typical fund that underperformed during this 15-year time period: It outperformed for a cumulative period of nine to 12 years. They conclude that three-, five-, and 10-year performance are very unreliable predictors of a fund’s long-term performance and should not be used. A fund’s long-term performance is hidden for extended periods and the benefit of it can only be harvested with long holding periods.

Source: “How Long Can a Good Fund Underperform Its Benchmark?” Paul D. Kaplan, Ph.D., and Maciej Kowara, Ph.D., Morningstar Manager Research, March 20, 2018

An important behavioral challenge is to keep clients in their seats when the inevitable underperformance of successful active funds occurs. Three years, often less, is as much underperformance as a client can emotionally tolerate. Then comes the demand to sell the “loser” and buy a recent “winner.” As Figure 1 shows, this often results in selling the long-term outperformers and investing in the long-term underperformers.

The irony of a Morningstar study arguing against using three-, five-, and 10-year performance for picking a fund should not be missed, as these returns are the basis for its widely used Five Star fund ratings.

Source: AthenaInvest, based on Morningstar Style Box methodology

The style grid’s widespread adoption distorts manager behavior by incenting them to stay in their “style box,” while at the same tracking an arbitrarily assigned benchmark. Research reveals the cost to investors of this style grid requirement related to minimizing both style drift and tracking error.

A study by Russ Wermers of the University of Maryland on the causes and consequences of style drift reports that the greatest “drifters” outperform those that drift the least by 300 basis points. This is because fund managers are unable to successfully implement their strategies because they must purchase stocks other than their best idea stocks as a way to minimize drift and tracking error, as measured relative to their arbitrarily assigned benchmark.

The wholesale adoption of the style grid has created strong performance-destroying incentives within the industry. Among other things, it is a major contributor to the widespread emergence of “closet indexing.”

So, if past performance and the style grid are unreliable selection criteria, what is a reliable alternative? It turns out manager behavior, represented by consistently pursuing a self-declared strategy while taking high-conviction equity positions, is predictive of future performance where past performance is not.

Investment strategy—or process or methodology—is the actual way a manager goes about analyzing, buying, and selling investments. Strategy encompasses the manager’s general approach to stock picking as well as the specific elements on which the manager focuses.

As an example, a Valuation manager (one of the 10 equity strategies to be introduced shortly) identifies and invests in undervalued stocks. The elements used by the manager to implement the Valuation strategy might include P/E ratios, valuing future cash flows, or being a contrarian. Drilling down further, the specific criteria used by the manager, such as purchasing stocks with a P/E of less than 15, are the manager’s “secret sauce” and are not part of strategy categorization.

Armed with this basic, yet essential understanding of how professionals manage portfolios, organizing funds around investment strategy is intuitively appealing. Anyone who has looked at a large universe of managers quickly realizes there is a broad spectrum of investment strategies and a wide range of specific investment elements.

Identifying the strategy of U.S. and international active equity mutual funds is accomplished by gathering “principal investment strategies” information from each fund’s prospectus (SEC-mandated, 1998). This is an approach that can be taken by advisors. Management behavior as captured by a self-declared strategy is an important pillar of our investment approach at AthenaInvest. Thus, we have developed a formal strategy-identification algorithm. This algorithm has been fine-tuned using an iterative process involving manager interviews, gathering principal strategy information, eliminating keywords that generate false signals, and settling on a manageable number of strategies.

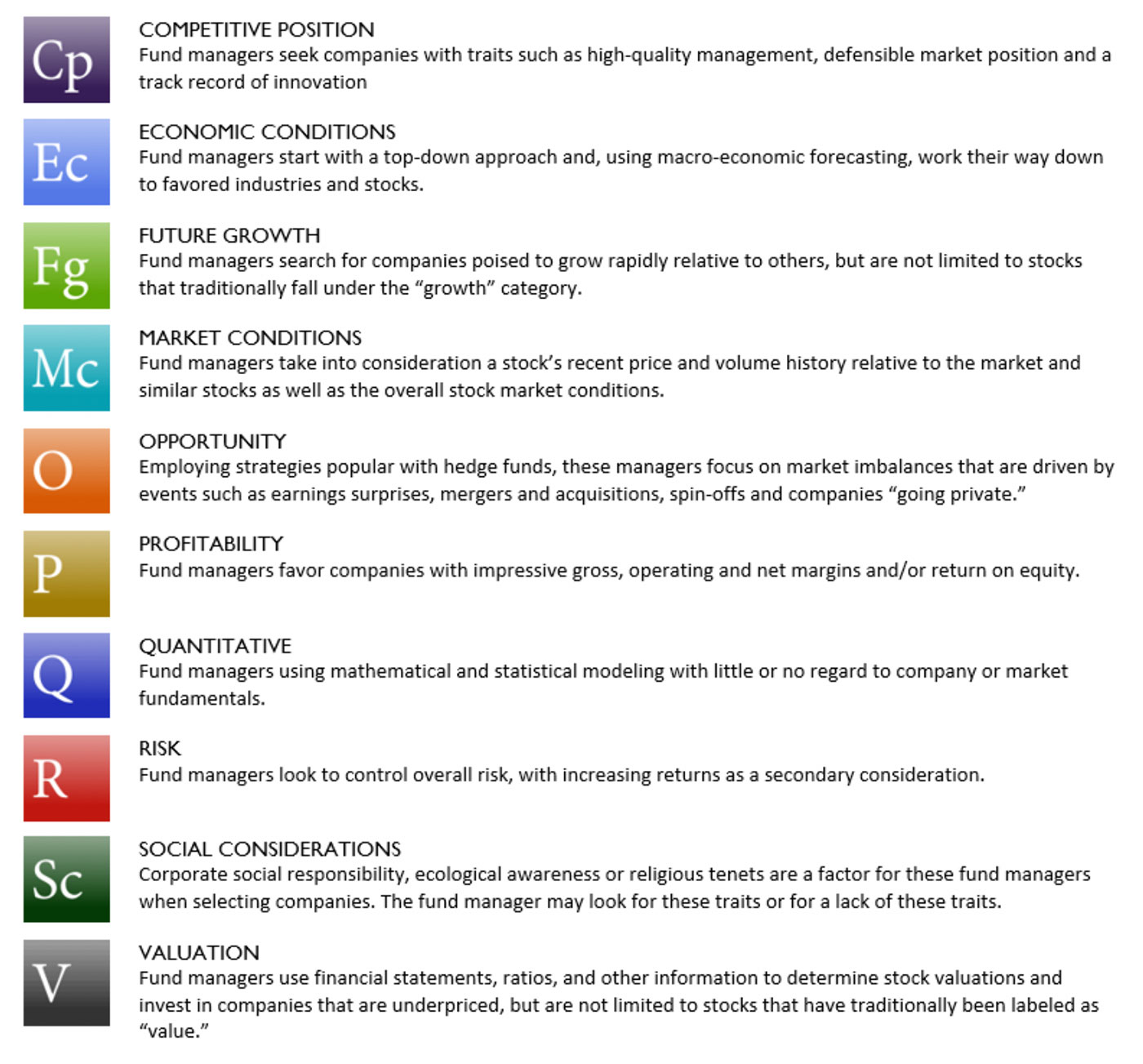

Over the last 13 years, tens of thousands of pieces of strategy information have been gathered for the 3,000 or so (ignoring share classes) U.S.-based active U.S. and international equity mutual funds. The identification algorithm assigns specific strategy information to one of 40 elements (i.e., the specific things managers do to implement their strategy), which are then assigned to one of 10 equity strategies. The 10 equity strategies are described in Figure 3.

Source: AthenaInvest

For example, Competitive Position managers focus on business principles, including quality of management, market power, product reputation, competitive advantage, sustainability of the business model, and history of adapting to market changes. Economic Conditions managers take a top-down approach based on economic fundamentals. And so forth for the other eight strategies.

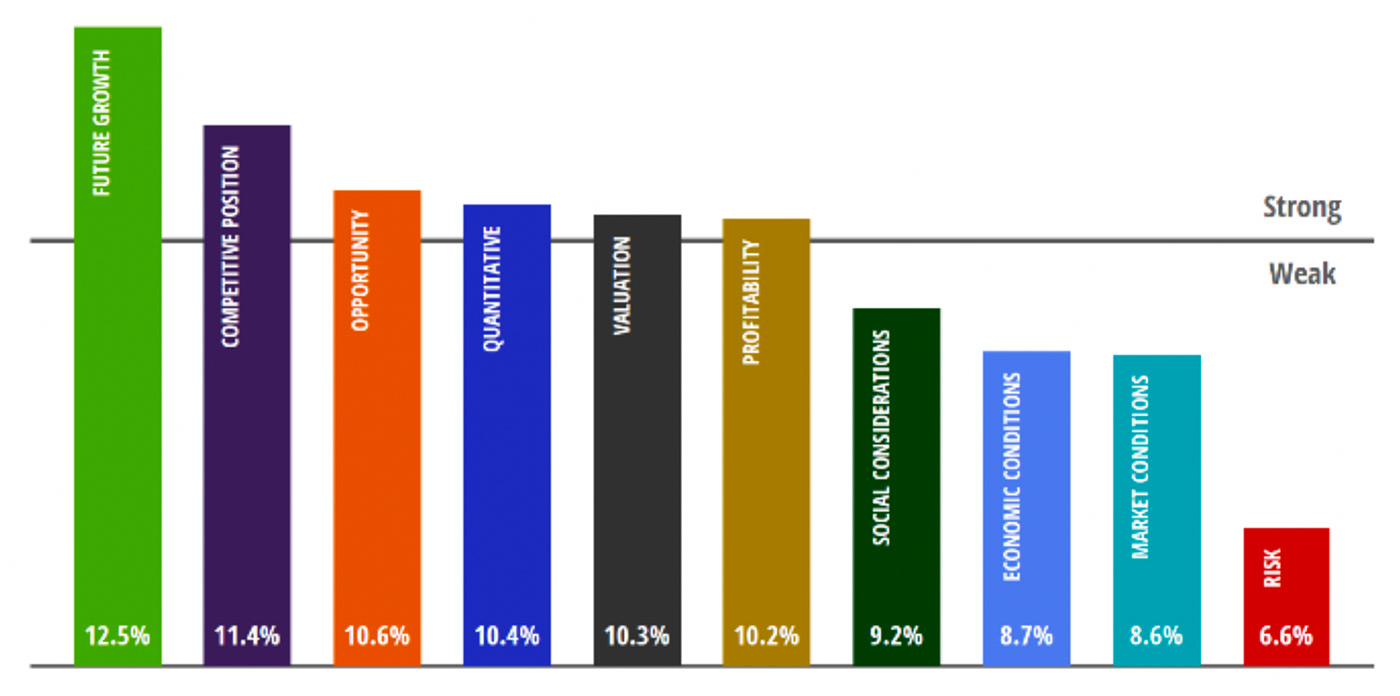

The AthenaInvest strategy database is updated monthly and has captured data starting from 1980. This is a self-identification process, so the number of funds varies across strategies. Strategy benchmark performance is presented in Figure 4 (average net returns across all funds in a strategy each year from 1980 through 2018). Future Growth has been the top-performing strategy, followed closely by Competitive Position. The worst-performing strategy has been Risk, trailing Future Growth by nearly 6% annually.

Source: AthenaInvest

A popular approach for active equity portfolio construction is to diversify across style boxes by investing in a small-cap value fund, a large-cap growth fund, and so on for the nine or more boxes. Strategy diversification is a similar concept in that you invest in funds pursuing different strategies.

Strategies provide superior diversification relative to style boxes as demonstrated in this study I authored, which details a series of tests comparing the two frameworks. A straightforward way to build a strategy-diverse portfolio is to select a fund from each of the 10 strategies.

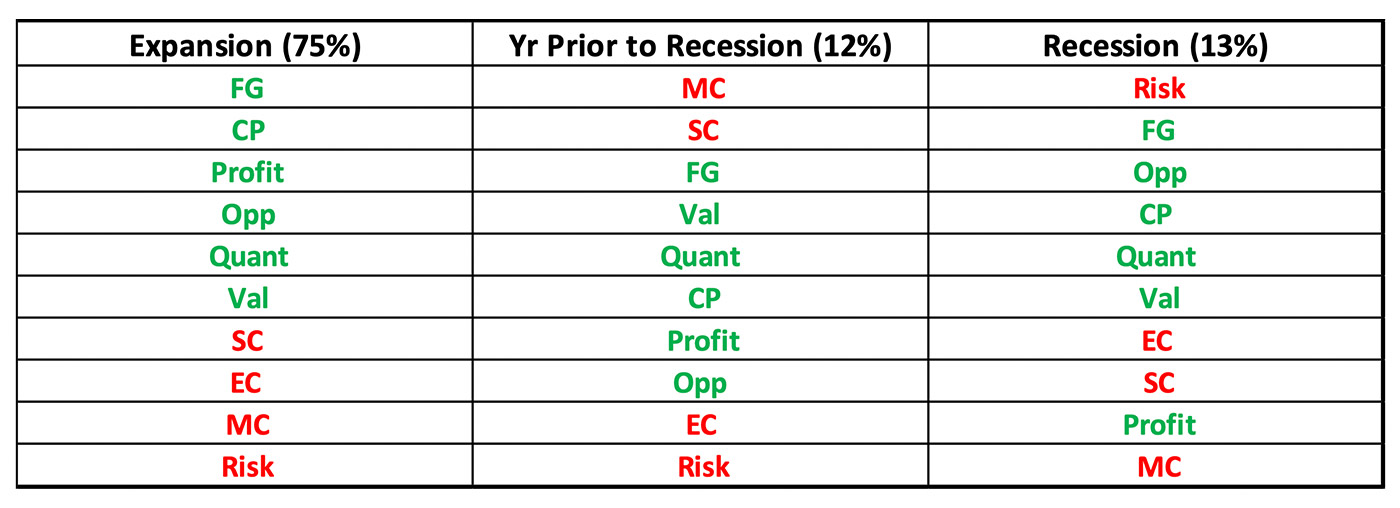

How do strategies perform over the business cycle? The results are ranked from best to worst in the following table.

Sources: National Bureau of Economic Research, Morningstar, and AthenaInvest

Over this 40-year time period, the economy expanded during 87% of the months and was in one of five recessions 13% of the months. The expansion year prior to a recession represented 12% of the months. For the expansion months, strategy performance ranks are similar to the long-term ranks reported in Figure 4.

Future Growth, Competitive Position, Quantitative, and Valuation, shown in green, are among the top six performers regardless of where we are in the business cycle. There is a case for including these four strategies as core investments in any active equity fund portfolio. One could easily argue for including Opportunity and Profitability, also shown in green, as strategic investments as well. These six strategies account for nearly 90% of U.S. active equity mutual funds, so avoiding the bottom four strategies excludes roughly 10% of available funds.

Clustering managers based on their self-declared strategy avoids the problem of comparing funds that are actually pursuing very different investment approaches. Other benefits include the following:

- Managers are free to pursue their stated investment strategy, unconstrained by an arbitrarily assigned style box.

- Managers following similar investment processes are grouped together.

- Strategy-based peer groups remain stable over time, allowing for long-term comparisons.

- Fund performance is more correlated within strategies and less correlated across strategies.

The strategy framework helps diversify an equity portfolio beyond capitalization and P/E by investing in funds with different performance patterns. If portfolio managers prioritize the pursuit of their strategy above style grid categorization, and do so consistently, financial advisors and investment consultants are able to select funds and build portfolios that work well in a range of market conditions.

Holding one’s own strategy stocks (the stocks most held by a fund’s strategy peer group) is the basis for a manager’s consistency measure. Strategy consistency allows a fund to move about the entire equity universe in pursuit of a strategy. Analysis shows this is a performance advantage compared to style-box-constrained funds that are limited to a fixed universe of market-cap, P/E stocks (288,000 fund-month observations, 1997–2017). That is, strategy consistency begets style drift and leads to superior performance.

Taking high-conviction positions also comes with important performance gains. If a fund invests in top 10 stocks, as measured by before-the-fact relative-portfolio weights, the fund’s alpha increases by 6.1 basis points for every 1% increase in top 10 holdings (analysis of a data set of 44 million stock-month equity fund holdings, 1/2001–9/2014). Performance also improves with increased investment in the next 10 stocks. But it deteriorates with increased investment in stocks outside of the top 20. Investing in best idea stocks helps performance while investing in low-conviction stocks hurts performance.

The concept of investment strategy is widely known and discussed in the industry. Strategy is not only an intuitive way of thinking about manager behavior, but it also provides a superior framework for understanding investment management.

Manager behavior, represented by consistently pursuing a self-declared strategy while taking high-conviction equity positions, is predictive of future performance where past performance and the style grid are not. The best funds are characterized by high style drift and tracking error while holding a smaller number of stocks and managing a smaller fund with assets under $1 billion.

A strategy-based approach yields a clearer picture of markets and, in turn, investment manager behavior. The resulting framework can be used to organize, rate, and select funds; build and manage portfolios; and evaluate investments and markets in general. Research reveals that moving from style boxes to strategies leads to superior results for clients.

Editor’s note: Proactive Advisor Magazine wants to thank Dr. Howard and AthenaInvest for contributing this article to our publication. Please visit AthenaInvest to register for a monthly “Behavioral Viewpoints” article.

C. Thomas Howard, Ph.D., is the founder, CEO, and chief investment officer at AthenaInvest Inc. Dr. Howard is a professor emeritus in the Reiman School of Finance, Daniels College of Business at the University of Denver. Dr. Howard is the author of the book “Behavioral Portfolio Management” and co-author of “Return of the Active Manager.” AthenaInvest applies behavioral finance principles to investment management and also provides advisor coaching and educational resources.

C. Thomas Howard, Ph.D., is the founder, CEO, and chief investment officer at AthenaInvest Inc. Dr. Howard is a professor emeritus in the Reiman School of Finance, Daniels College of Business at the University of Denver. Dr. Howard is the author of the book “Behavioral Portfolio Management” and co-author of “Return of the Active Manager.” AthenaInvest applies behavioral finance principles to investment management and also provides advisor coaching and educational resources.