Do behavioral biases also affect financial advisors?

Do behavioral biases also affect financial advisors?

Individual investors have well-documented behavioral biases that can be detrimental to their investing health. Do financial advisors exhibit similar behavioral weaknesses?

A few years ago, I was reading an article about Dennis Gartman, a well-known market professional and frequent financial news commentator. According to Financial Advisor’s story, “A risky crypto bet dented Dennis Gartman’s retirement account.” Gartman reportedly had told CNBC less than two months prior to the story that bitcoin “is nonsense.”

While the details of Gartman’s trade are unimportant, he wrote in his newsletter back then, “Friday was one of the worst days we have suffered through in a very long while. … Lessons have to be learned again and again and again it seems. Or at least we apparently have to learn them over and over and over again.”

The COVID-related market volatility seen in 2020 and 2021—not to mention the advent of widespread trading in cryptocurrencies, NFTs (non-fungible tokens), SPACs (special purpose acquisition companies), and “meme stocks”—provided plenty of opportunities for investors of all stripes to experience various emotions along the fear-greed spectrum.

The COVID-related market volatility seen in 2020 and 2021—not to mention the advent of widespread trading in cryptocurrencies, NFTs (non-fungible tokens), SPACs (special purpose acquisition companies), and “meme stocks”—provided plenty of opportunities for investors of all stripes to experience various emotions along the fear-greed spectrum.

Just take a look at the volatility in many of the “stay at home” stock plays versus “reopening” ticker symbols. Peloton (PTON) is one of the prime examples, making a round trip from about $20 per share in March 2020 to an all-time high in January 2021 over $160—and back down to the $20s in 2022.

And beyond individual stock stories, the macro U.S. equities environment was quite unusual and challenging during 2020 and 2021. 2020 included what was acknowledged as the fastest market fall of at least 30% in history—and the fastest rebound from a bear-market low for the Dow Jones (DJIA) in about three decades, according to Dow Jones market data.

2021 then saw the greatest number of new market highs since 1995 and the three major indexes up on average over 20%. But just five stocks accounted for about 50% of S&P 500 gains for much of the year. And Yardeni Research noted that close to 40% of all stocks were below their 200-day moving average in the latter months of the year. An analysis by FactSet found that of the combined large-cap companies in the S&P 500 and NASDAQ 100, 94 were in a bear market as of the last week of the year—“down at least 20% from their 2021 intraday highs.”

One financial advisor I spoke to in 2022, who holds advanced certification in technical analysis, told me 2021 was “the most counterintuitive market” he had ever seen. He freely admitted that he started to lose faith in some of the internal market indicators he has followed for years. As it turns out, this advisor’s bearish instincts and analysis might have been right on the money—if months early. The start to 2022 for equities was disappointing, especially for the tech sector.

Behavioral bias doesn’t just impact retail investors

Several articles in our publication have addressed the growing prominence of behavioral finance theory in the investment world and explored some common behavioral biases for self-directed investors.

But what about financial advisors and other investment professionals? Are they similarly affected by biases? (Gartman’s story—and the advisor mentioned above—certainly appear to be examples.)

Proactive Advisor Magazine has interviewed successful financial advisors from all corners of the United States over the past eight years. Virtually all of these financial advisors subscribe to a very disciplined financial and investment planning process for their clients.

But many have discussed making past mistakes in investment judgment, process, or implementation. And research studies document that almost every textbook example of behavioral finance bias or emotional decision-making could be ascribed to financial advisors and other industry professionals at one point or another in their career.

A 2015 article from the CFA Institute (home of the Chartered Financial Analyst credential) pointed out,

“Heuristics—mental shortcuts—and other biases continue to affect some of our professional choices, leading us to make mistakes. For a gifted few in the industry, biases are a source of alpha. But for many others biases impose a cost—a price paid for irrationalities.

“Financial markets reflect these irrationalities and collective biases.”

Three of these behavioral biases stand out from my discussions with financial advisors.

1.Trend-chasing bias. Today’s financial advisors have access to institutional-type strategies built with sophisticated algorithmic models by third-party investment managers. In and of itself, that is a real plus for their clients. But the advisor still must make fundamental portfolio allocation decisions. Unfortunately, on occasion, the advisor may “chase” the best-performing strategies of the previous quarter or year.

One representative of a prominent third-party investment firm told me,

“One experience advisors may have had is choosing to use a back-tested strategy for client portfolios after it had a good and long run upward. We often watch strategies do well and then attract a large amount of assets due to their recent success. There is nothing inherently wrong with that. However, such strategies then might experience a period of sideways or drawdown performance. That normal, yet less-than-stellar, performance leads performance-chasing advisors (or their clients) to quit the strategy before the next period of positive performance.”

A diversified portfolio of several different actively managed strategies that are not highly correlated, he says, can offer advisors’ clients higher probabilities of success over the long term and throughout bull and bear market cycles.

2. Familiarity bias. Like retail investors, some financial advisors will naturally be inclined to stick with the familiar. Third-party asset managers can offer strategies that have few restraints when it comes to asset classes, geographies, or strategy type (i.e., mean-reverting versus trend-following, or even inverse to an index). It is important for advisors to continually educate themselves as to new strategic offerings, weighing not only the pros and cons of each strategy for their clients but also how each one might fit as part of a dynamic, risk-managed portfolio of strategies.

2. Familiarity bias. Like retail investors, some financial advisors will naturally be inclined to stick with the familiar. Third-party asset managers can offer strategies that have few restraints when it comes to asset classes, geographies, or strategy type (i.e., mean-reverting versus trend-following, or even inverse to an index). It is important for advisors to continually educate themselves as to new strategic offerings, weighing not only the pros and cons of each strategy for their clients but also how each one might fit as part of a dynamic, risk-managed portfolio of strategies.

3. Herd mentality. This can manifest itself in different ways for financial advisors, most often prompted or reinforced by the behavior of their clients or their peers. In today’s long-running secular bull market, clients tend to become more return-oriented in their expectations as the market continues (until recently) to make new high after new high. Although these same clients may have explicitly agreed to an investment plan that was well-aligned with their risk profile and incorporated several strong elements of risk management, their devotion to a disciplined approach may start to waver in the face of a rising market. Advisors need to continually reinforce the long-term benefits of an actively managed approach that will mitigate risk when the market inevitably turns around or goes through bouts of volatility.

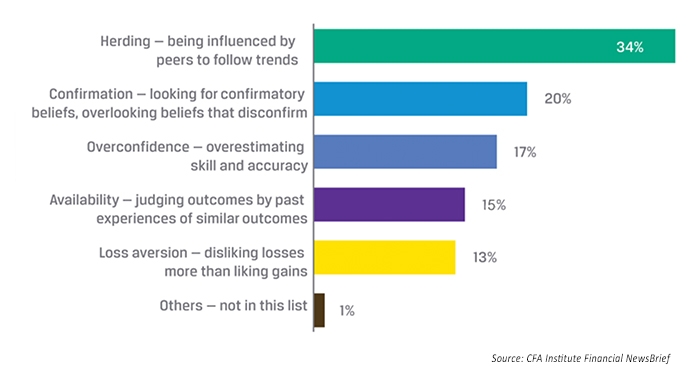

The CFA Institute once conducted a survey asking its professional readership to select the behavioral bias that “affected their investment decisions the most.”

***

These types of biases, many experts agree, tend to be most pronounced at market extremes. Investors of all types are more prone to take on too much risk in elevated markets and are susceptible to making poor decisions in highly volatile or declining markets. Nobel Prize–winner Richard Thaler has remarked, “Investors make mistakes—and they make mistakes because they are human.”

Rules-based, quantitative strategies can help take human emotion out of investment decision-making, both for financial advisors and their clients. They have been designed to perform competitively during favorable bull market environments and to aggressively manage risk in hostile markets. To take full advantage of such strategies over complete market cycles, the not-so-simple challenge for many financial advisors might be consistently applying their wisdom about client behavioral biases to their own investment management processes.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Proactive Advisor Magazine. These opinions are presented for educational purposes only.

This article was first published in Proactive Advisor Magazine on Jan. 31, 2018, Volume 17, Issue 4. Certain content was updated to reflect current information.

New this week:

David Wismer is editor of Proactive Advisor Magazine. Mr. Wismer has deep experience in the communications field and content/editorial development. He has worked across many financial-services categories, including asset management, banking, insurance, financial media, exchange-traded products, and wealth management.

David Wismer is editor of Proactive Advisor Magazine. Mr. Wismer has deep experience in the communications field and content/editorial development. He has worked across many financial-services categories, including asset management, banking, insurance, financial media, exchange-traded products, and wealth management.