Behavioral issues around time, age, and generational identity are underappreciated

Behavioral issues around time, age, and generational identity are underappreciated

Time-related illusions create age and generational-identity biases that are subtle but can have significant effects on an advisor’s client relationships and how investment alternatives are evaluated.

By now, almost all financial advisors have been exposed to the basic behavioral-finance narrative: People can be hindered in the decision process by a variety of emotions, heuristics, instincts, and biases that are hardwired into our subconscious mental machinery.

Common among these are biases such as herding, framing, loss aversion, and mental accounting. But there are many more. Three related biases that get much less airplay, but which can be highly important to advisors, are time, age, and generational identity.

Time-related biases stem from temporal illusions we fall victim to but which predominantly go unnoticed. Often, they are overshadowed by more prominent biases that they interact with, which also tend to be easier to understand. The fact is that our minds deal with time in quirky ways, some of which are not yet fully understood.

Since time is a critical element of investing, temporal biases and illusions are core to an advisory relationship. An obvious place where time-related misperceptions crop up is in retirement planning, where people pervasively underestimate what they will need and how much they should currently save to meet their goals. But the problem goes deeper into all situations where the time value of money is relevant, and they are pronounced with regard to investments overall and particularly time-specific financial instruments such as bonds, options, target-date funds, and private equities.

Understanding the time value of money is, of course, essential to investing and financial planning. But in client minds, it tends to be much more of a behavioral concept rather than a strictly financial one.

The first time an advisor presents calculations to a client on how much they need to save for retirement, the difference usually becomes apparent. Younger clients, who are trying to build wealth at the same time they are paying off student loans, taking on the expense of their first home, and expanding their families struggle mightily with the mental trade-offs of current debts and expenses versus the need to plan for the future, regardless of what the numbers suggest they should do.

Everyone gets that the earlier you start saving, the more you benefit from compounding, but try telling that to someone in their 20s or 30s with $150,000 of student debt, a baby on the way, and a one-bedroom apartment. Part of the hesitation is a common human trait to view the future as essentially infinite and to thereby assume that the wealth you will inevitably accumulate later will bail you out.

There is no magic formula for making these trade-offs, and to add to the dilemma, spouses won’t always see them the same way. To begin with, the numbers do not necessarily present a cut-and-dried solution. They can show the benefits of paying down debt, owning a home, and putting money in a tax-deferred account, but there are a ton of assumptions made about interest rates, long-term investing returns, personal earnings growth, and living expenses that get distorted by our perceptions of time. Beyond that, there are trade-offs that are nearly impossible to quantify, like the lifestyle sacrifices, the unforeseen expenses, and the uncertainties of career paths.

These, however, are just the surface issues that we’re all aware of. The underlying perceptions go a lot deeper.

Our minds seem to have a complex relationship with time. We dread each moment of a bad experience, but we allow good experiences to fly by without even being aware of time. We tend to compress time that has gone by while seeing the time we have in front of us as practically forever. We give more weight to money we can have now than money we can have tomorrow, next month, or next year, and it’s much more weight than the logic of time value would justify.

Perhaps most dangerously, we see ourselves living far into the future, and enjoying our wealth, but cannot even begin to fathom how many nonworking years that might represent and what those years will cost. Sadly, the reasons why so many people live paycheck to paycheck are not just financial.

Aging and the risks of longevity for clients are well-covered subjects with advisors. After all, melding our financial wealth, resources, and goals with our aging process is the essence of what advisors do for all of us. But most of the attention is on the expenses, needs, and financial objectives associated with aging, with far less on the psychological metamorphosis that takes place, not just for the clients, but for the advisor as well.

That doesn’t mean the advisor should be an age counselor to clients, but it does mean that the client’s perceptions of risk, wealth preservation, social goals, and legacy plans will likely be impacted by age. Advisors who recognize that won’t be blindsided when it occurs. In addition, advisors also need to recognize that their own view on these subjects will change and color how they handle the changes in their clients.

Aging can be an insidious process. It is endowed with the ability to hide in plain sight while being so subtle as to completely escape conscious awareness for long periods. On a day-to-day basis, the effects of aging are so slow and subtle that we all but ignore them. Over time, however, they clearly become significant.

A quip about age that is commonly made is that the older we get, the faster time seems to move (or the greater amount of time passes in a perceived interval). “This is because objectively measurable ‘clock time’ and purely subjective ‘mind time’ are not the same,” says Clifford N. Lazarus, Ph.D., in his article “Why Time Goes By Faster As We Age” in Psychology Today.

University of Virginia psychologist Peter A. Mangan conducted a study in 1998 that confirmed the effect. Dr. Mangan asked people in different age groups to estimate when three minutes had passed by silently counting one-one-thousand, two-one-thousand, and so on. People in their early 20s were accurate to within a few seconds, and some hit it right on the nose. Middle-aged subjects estimated that the interval was a good bit longer, and those in their 60s estimated that three minutes were up when three minutes and 40 seconds had actually elapsed.

Advisors face three immutable facts about aging:

- They will age.

- Their clients will age.

- The markets and investment landscape will change with age.

Of these three, some ongoing attention is generally paid to client aging, while not enough is paid to the other two.

A focus on financial planning helps advisors pay attention to client aging, at least in terms of the key life events and transitions that drive the need to revisit financial goals and strategies. But aging is a continuous process, and key life transitions merely punctuate our lives at irregular time intervals. The challenge is to stay on top of a client’s aging process more regularly. To do this, an advisor should use annual reviews to probe clients for age-related indications of changes in their thinking or perceptions—in addition to reviewing progress versus goals and possible lifestyle, health, or family changes.

The bigger problem is that the focus on clients tends to draw attention away from the advisor’s own aging process and the changes in the markets as well. These can both have a material impact on the advisor’s practice, affecting performance, client relationships, and exit or succession planning.

Some of the issues that arise from this are well addressed, such as the difficulty advisors face recruiting motivated and qualified younger advisors to their firms, or an age bias toward younger candidates in the first place. Lesser-known issues are trying to impose your generation’s investment preferences on clients from other generational groups and viewing the markets through the eyes of only one generation—yours.

Aging is (thankfully) a long, slow process. We don’t think in terms of how much we’ve aged since yesterday, or even last week or last month. Instead, our perception changes in measured leaps, usually associated with one or more of the various wake-up calls we get during our lives, like a job change, a divorce, a grandchild, a health issue, or even just hitting one of those big round-numbered birthdays.

This is all normal. But it’s not something an investment manager or advisor has the luxury of ignoring without it affecting his or her practice. Tapping into your own age-related changes may require self-analysis, or better yet, finding another advisor to perform it on you. What you will likely find is that you are not the same as you were five or 10 years earlier. At the very least, this could suggest the need for an updated public profile and possibly even an updated statement of investment strategy or philosophy to your clients. Explaining to your clients how your views have changed, based on your experience and knowledge acquisition over time, might have the positive side effect of opening their eyes to how their own outlook has changed as well.

One of the “tells” about how you are aging is your generational identity.

Generational differences are not uniform or universal, but they can be significant when present. For example, evidence of the effects of the Great Depression was found to be present not only among the generation of those living through it in their later years but even in their children and grandchildren. Today, the differences between baby boomers and millennials become particularly important, since many advisors are boomers and many of today’s up-and-coming investors are millennials—and because the differences brought on by the internet, smartphones, and social media make these generations a world apart in many ways.

We experience the pleasure of generational affinity through conversations and reminiscences with peers, or by attending a concert by the artists that were popular in our younger days. We also have shared cultural, political, and sociological reference points. But this affinity can also manifest itself in a collective discomfort or disagreement for some of the social norms of other generations. How often do we find ourselves put off by the practices of younger generations?

When this occurs, other biases such as representativeness and the halo effect kick in to cause stereotypes and might leave negative impressions, or at least a struggle to relate well. This then impacts human interactions such as hiring, partnering, and client relationships. If your client’s heirs exhibit generational characteristics that you have difficulty relating to, how can you expect to establish a productive relationship with them? Advisors should be aware by now of the need to be as bias-free as possible when dealing with people of different financial, sexual, political, cultural, or lifestyle orientations. Just add generational bias to that list.

We tend to view generational differences through a social lens, defining generations by the characteristics most visible to us, such as fashion, music, and politics. For financial advisors, however, the important differences lie much deeper and involve issues around risk and risk management, investment preferences, corporate responsibility, and other ESG issues. These are clearly less visible and must be obtained through open and frank discussions on these topics.

The biggest issue for advisors about generational identity is the disconnect that ultimately occurs between the perspectives of the advisor’s generation and those of younger generations. This disconnect can occur in two ways. The more obvious way is when the advisor disconnects from a younger client or prospect over views on subjects such as those mentioned above: risk, interest rates, bull and bear markets, alternative investments, business models, or issues such as sustainability and environmental impact. The differences aren’t usually polar opposites in perspective, but rather a difference in the degree of importance.

The second is when the advisor begins to disconnect with markets and investments. This occurs as the advisor’s perspective on market dynamics begins to get out of sync with markets that are influenced more by a younger generation of investors.

It is very easy to fall into the trap of thinking we understand the markets better with added experience. However, we typically evaluate risks and opportunities using the same rules of thumb we always have, and if those rules have changed in the marketplace, we can find ourselves making bad judgments. How many older advisors or investment managers can honestly say they were not highly skeptical about high-growth tech stocks (including Warren Buffett), especially after the dot-com bust? Caution was undoubtedly warranted, but many great opportunities were probably missed as well.

An inability to relate to those of other generations can have another effect that is far less evident—losing touch with markets or products that are incongruent with your generation.

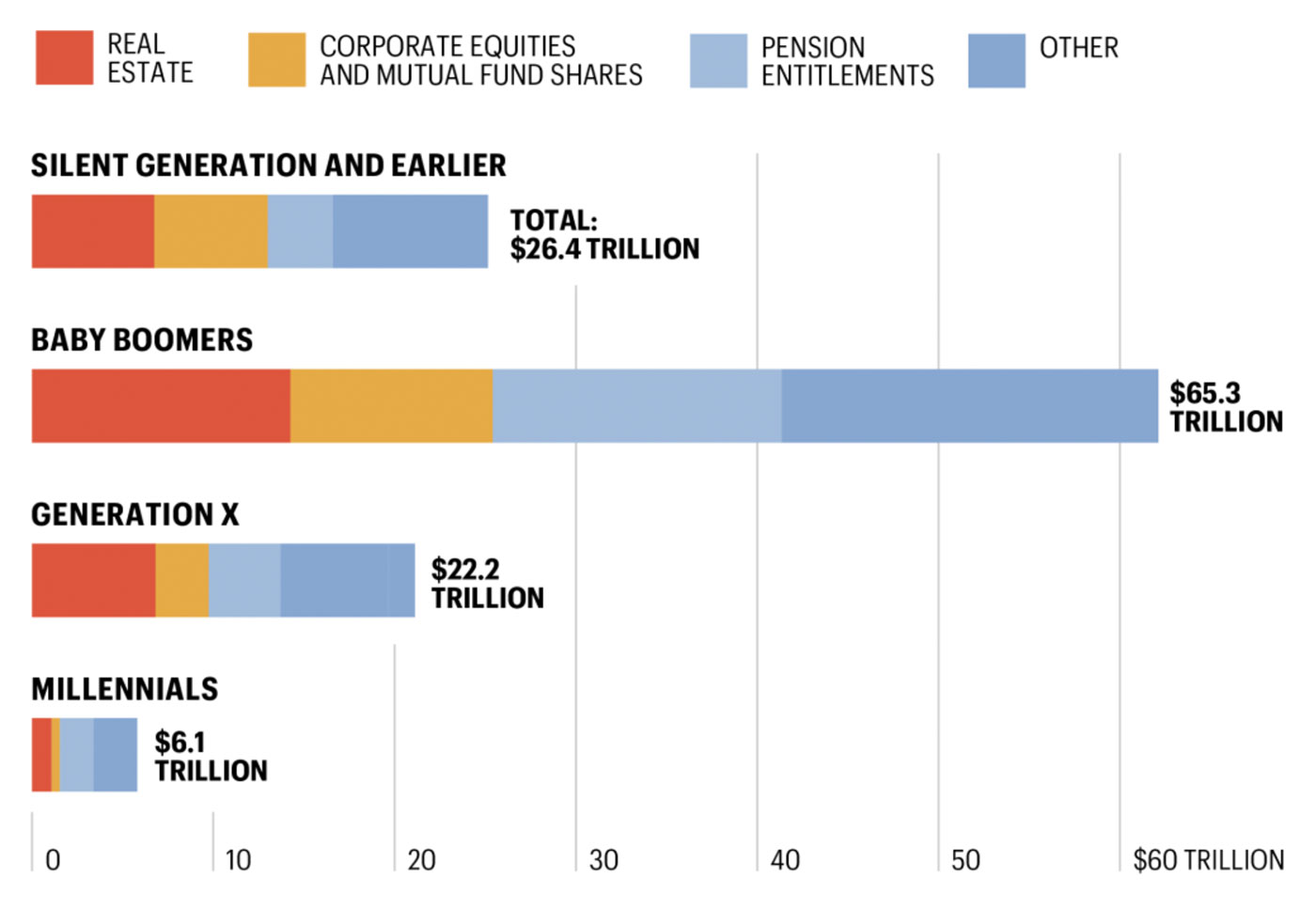

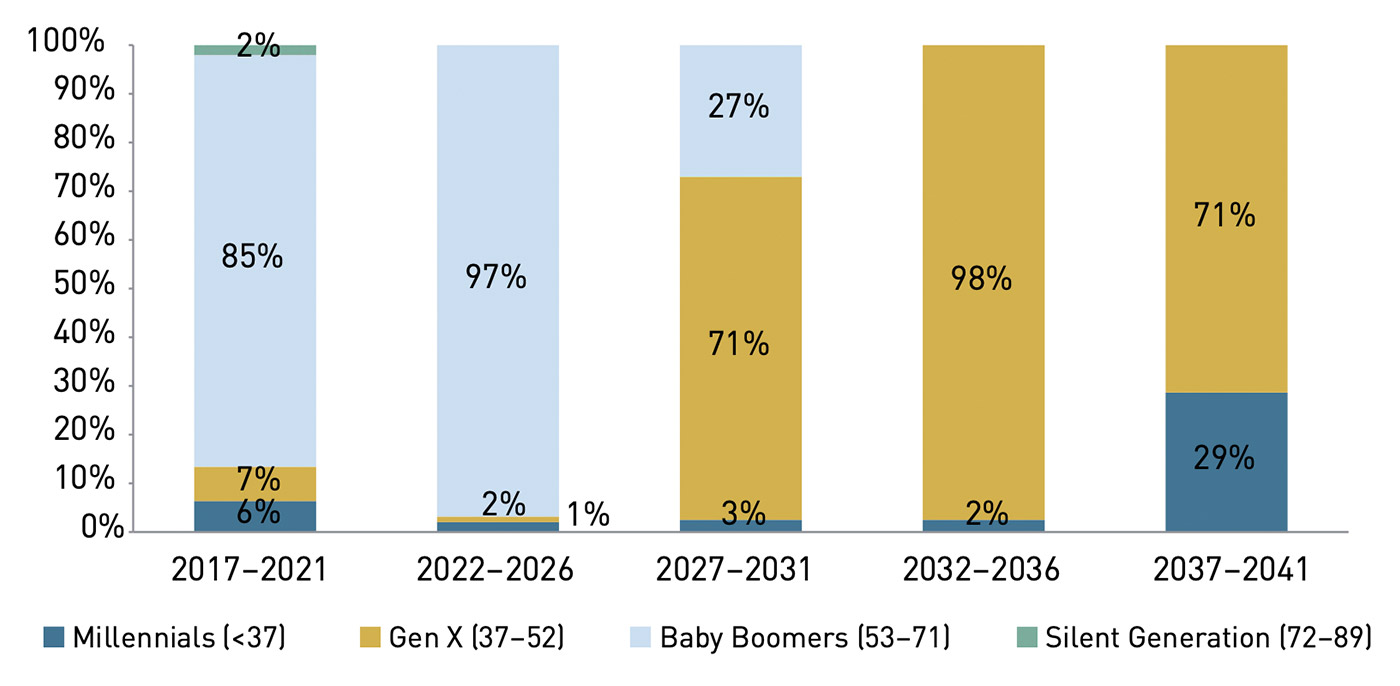

The importance of the next generation of investors (beyond baby boomers) to financial advisors cannot be understated. Figure 1 shows a 2020 look at different types of major investment/wealth categories broken out by generation. Figure 2 shows an estimate of how wealth will be transferred over the coming years and the changes in the generational mix.

Advisors will need to understand:

- Where the available assets will be in the future by generation.

- What the individuals and families of those generations will want and need in terms of financial planning.

- How those planning imperatives may influence investment selection and suitability, as well as how they fit with changes in the market environment and evolving investment strategies and products.

Note: As of Q1 2020. Does not include liabilities.

Sources: Fortune, Q3 2020 quarterly investment guide; Federal Reserve Board

Note: Ages as of 2018.

Sources: Investments & Wealth Institute, Cerulli Associates, U.S. Census Bureau, Internal Revenue Service, Bureau of Labor Statistics, Social Security Administration

Markets, as we all well know, are also highly intertwined with time. Mastering them is particularly challenging when the mantra of investing preaches the virtues of holding for the long term while our instinctive brains are tormented by the dynamics of day-to-day price action. The conflict between the short-term mind and the long-term mantra is palpable. But this is not the only issue we have with time and markets.

Nobel Prize–winning economist Robert Shiller tells us that people tend to view the markets as a “force of nature,” some grand power to be reckoned with like a flood or a hurricane. Do some advisors fall into that trap, despite knowing better? Those who do recognize that the markets are simply a very large collection of people tend to view it as the same people that were there yesterday, last week, or last year.

Either way, it’s easy to lose sight from day to day that the market changes because the participants change. It happens gradually, as one generation of investors gradually cedes the reins over to another. The new generation won’t necessarily have the same mindset, tools, or values that the former one had.

Like many other perspectives, our understanding of financial markets is often anchored in the time when we first studied it. Baby boomer perspectives on the market are very much defined by double-digit interest rates, the crash of 1987, mutual funds, and leveraged buyouts. Gen X perspectives are more defined by the internet boom, tech stocks, ETFs, and the crash of 2000. Millennial perspectives are being molded around the 2008 financial crisis, nonexistent interest rates, meme stocks, and bitcoin. As a new generation of investors becomes a more prominent part of the investing audience, their impact on markets changes. It happens too slowly for you to consciously adjust to it, but one day you wake up and realize your perspective on the markets is noticeably off.

It’s been widely publicized that the investors driving trends in the markets associated with meme stocks and cryptocurrencies are largely in their 20s and 30s. Millennials are also now the largest group of home buyers and are driving trends in sustainable investing. If you cannot appreciate how the younger generation thinks, spends, saves, invests, and communicates, you can find yourself decidedly out of sync with what is happening in today’s markets.

To be successful, managers and advisors may need to think like those one or two generations younger than themselves, or at least understand the differences. Applying the logic and values of one generation to markets composed of multiple generations of investors won’t necessarily work in all areas.

***

Our relationship with time, age, and generational identity is subtle and variable. We confront it in many aspects of daily life, but all too infrequently fail to appreciate their impact on the financial decisions we make or advice we give. Advisors who understand these factors will be more in tune with their clients as well as the markets.

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.