The case for active over passive investing is really about investor behavior

The case for active over passive investing is really about investor behavior

Most investors do not behave in ways that are consistent with the theoretical benefits of long-term passive investing. They will likely be better served by an actively managed approach.

The fact that we are still debating the merits of active versus passive investing more than 40 years after John Bogle launched the first index investment trust is a testament to how central that debate is to the very essence of investment management—and how rooted the underlying issues are in deep-seated investor behavior.

It also reflects that a simple comparison between an index fund and a group of actively managed mutual funds is an oversimplified representation of the issue. It happens to be a handy comparison because the data is widely available in the public domain, but it doesn’t necessarily reflect the realities involved. A behaviorist would note that most people don’t actually behave in ways that map to a totally passive strategy and that independent investment managers do not behave in a manner that is similar to the managers of public mutual funds. From this perspective, the whole debate is built on comparisons that do not accurately represent real behavior on either side, thus putting investor behavior itself at the core of the debate.

Nobel laureate and behavioral science pioneer Daniel Kahneman said, “Economists think about what people ought to do. Psychologists watch what they actually do.” This statement may have more relevance to active and passive investment management than people realize. Using an index fund to illustrate the returns from a passive strategy represents the economist’s approach—a representation of what people should do to achieve a long-term return equal to that of the broad market. The economist’s numbers may be valid, but the basis in behavioral reality is not. A psychologist would point out that buying and holding an index fund for a very long time is simply not how most people behave, even though the opportunity has been there for decades.

Both sides of the data comparison ignore behavioral reality

A single index fund fails to reflect behavioral reality since few investors or managers toss all of their assets into a single broad index fund and let it sit there for a decade or two. The pull of emotions, biases, and the need to exert control are simply too strong for most investors to ignore. As a result, even investors with the right intentions stray from a strict adherence to an index fund, thereby negating its hypothetical long-term benefit. And because there are so many index funds for different groups and sectors, a more common approach involves the construction of portfolios of different index funds, leading to periodic reallocations and rebalances, thereby injecting an active management component back into the equation.

A single index fund fails to reflect behavioral reality since few investors or managers toss all of their assets into a single broad index fund and let it sit there for a decade or two. The pull of emotions, biases, and the need to exert control are simply too strong for most investors to ignore. As a result, even investors with the right intentions stray from a strict adherence to an index fund, thereby negating its hypothetical long-term benefit. And because there are so many index funds for different groups and sectors, a more common approach involves the construction of portfolios of different index funds, leading to periodic reallocations and rebalances, thereby injecting an active management component back into the equation.

Performance numbers on actively managed mutual funds may likewise misrepresent the behavioral reality of independent portfolio managers. Heavily constrained by the Investment Company Act of 1940, public fund managers are required to hold cash for redemptions, are restricted in leveraging or shorting, and are prohibited from using derivatives to hedge their holdings. As such, painting independent managers who are not bound by the 1940 Act with the same performance brush can be highly misleading.

Active mutual fund managers are also locked into their stated objectives and generally manage with the intention not to veer far from their benchmarks. So, comparing the performance of a single index fund to a group of actively managed mutual funds is almost like comparing you to a picture of you and declaring the real you to be better looking.

The allure of control and engagement

Choosing an index fund over active investment management removes the sense of control over one’s investment. While this is a plus for many people who don’t want control, or feel ill-equipped to handle it effectively, it does not fit everyone’s needs.

Risk tolerance and the desire for control are not constants among the investing populace, and behavioral studies also show that they vary with age, wealth, and life circumstances, not to mention the market environment. Many investors need tailored, flexible strategies that can dial the risk level up or down according to the variables mentioned above, getting more defensive or aggressive as conditions warrant. In most cases, active managers can supply these strategies better than the individuals themselves.

A final observation regarding engagement is that a lot of people with 401(k) programs or self-directed IRAs have control over those assets, but they are truly ill-equipped to manage them properly. Plan administrators provide only minimal education and are prohibited from making recommendations. I remember one example of a woman who spread her money equally over the 20 funds available in her 401(k) plan, thinking she was maximizing her diversification that way. Other plan participants select the index-fund option out of a paralysis about choosing from the other available options—they would like active help, but either it simply isn’t available to them or they are unaware that a growing number of plan administrators now provide that opportunity. Active portfolio management in these plans could undoubtedly benefit many of these employees, helping them to manage risk and feel more secure about their retirement fund.

The passive return argument and “hindsight bias”

Looking back over a 20- to 30-year horizon or longer, it is very easy to show how the markets recovered from sell-offs as large as those in 1987, 2000, and 2008. But that’s because there is now absolute certainty surrounding those rebounds. The problem with looking back at past events is that we experience “hindsight bias”—a distortion of the probabilities of a past event by the fact that we know the outcome with certainty. In other words, we forget how uncertain (and in some cases downright scary) those prior events were when they occurred.

As the markets were tumbling out of control in 2008 and prominent financial firms were going under, people might have been well-justified to have pulled their money out or reduce their exposure. Today’s 10-year or 20-year returns for passive investing assume that one remained completely invested during that entire period. For many people, that doesn’t jibe with the realities of the time and thus reaches a conclusion that might be theoretically correct but behaviorally invalid.

The illusion of the long-term average

Behavioral studies show that the human mind has systematic quirks about the way it deals with probabilities and statistics. Kahneman and psychologist Amos Tversky addressed some of these in their landmark paper on prospect theory, and they are as much a part of behavioral finance as the more well-known cognitive and emotional biases we exhibit. Among other things, prospect theory notes that people tend to distort actual probabilities, using instead a subjective version of those probabilities referred to as “decision weights.”

Behavioral studies show that the human mind has systematic quirks about the way it deals with probabilities and statistics. Kahneman and psychologist Amos Tversky addressed some of these in their landmark paper on prospect theory, and they are as much a part of behavioral finance as the more well-known cognitive and emotional biases we exhibit. Among other things, prospect theory notes that people tend to distort actual probabilities, using instead a subjective version of those probabilities referred to as “decision weights.”

We also tend to confuse averages with means, and we tend to underestimate variance from the mean. You might be tempted to move to a city like Lakeport, California, once you see that the average temperature all year is 56 degrees and the average high temp is a balmy 72. But when you get there, prepare for summers in the 90s and 100s and winters as low as the teens and 20s. Similar surprises play out on the stock market. The long-term average return over the last century for the S&P 500 is just under 10%, yet the annual returns are rarely within one or two percentage points of 10% and have often been 20-30 percentage points above and below the average.

An analysis of rolling 10-year returns from passive funds in a recent article from Vanguard showed that “contrary to expectations, the average index-fund investor hasn’t exactly tracked the broad market. In fact, the excess returns versus those of a total market fund have fluctuated greatly, outperforming or underperforming the market by nearly 14% and 8%, respectively, at various intervals. … This suggests index-fund investors have been building active portfolios.”

So, while Nobel Prize-winning academics tell us that the market is such an efficient pricing mechanism that beating it through active management does not produce excess returns after transaction costs and management fees, they are correct. But they speak of averages, not variance. To be sure, there will be plenty of exceptions to the average—the laws of chance assure that, even before skill is considered at all. And while few exceptions will persist over a significant time period on a consistent basis, the human mind is a sucker for the laws of chance, as any casino will happily attest. The same mental aberrations that keep people flocking to lottery tickets and blackjack tables will also drive them to managers who they believe can help them beat the stock market. Right or wrong, average returns spell mediocrity for many people, and they would rather take the extra risk than settle for it.

Context bias: What a difference a half-century makes!

When John Bogle introduced the first index fund in 1975, mutual funds were enjoying so much success that the idea of a nonactive one was viewed not just with a yawn, but with disdain. The notion of an actively managed mutual fund was so ingrained across the population as a tribute to U.S. capitalism that some competitors tried to position Bogle’s index fund as “un-American.”

When John Bogle introduced the first index fund in 1975, mutual funds were enjoying so much success that the idea of a nonactive one was viewed not just with a yawn, but with disdain. The notion of an actively managed mutual fund was so ingrained across the population as a tribute to U.S. capitalism that some competitors tried to position Bogle’s index fund as “un-American.”

For the average retail investor, mutual funds offered a way to achieve both diversification and professional management in a single instrument. The alternative was to manage your own assets, or to rely on a broker’s recommendations, which generally fell into the category of the hot stock of the week. In addition, America was going through a post-WWII business boom that fueled powerful industry giants such as IBM, General Electric, and General Motors—companies that did have something of a patriotic appeal to them. With this backdrop for context, passive index investing drew little fanfare.

Fast-forwarding to today, the amount of money flowing into passive funds is growing so rapidly, they are not only pulling in more money than actively managed funds, they are pulling money out of active funds. There are no consistent figures to indicate how much money is coming out of actively managed accounts with registered advisors to go into passive funds, or how many advisors themselves have now shifted to passive funds for their clients, but there is enough anecdotal evidence to know that both are significant. In the 401(k) world, where assets are substantial, investors don’t always have the option of a privately managed account, or they are unaware that they do have that option and therefore believe they are faced with only a choice of mutual funds. Passive index funds serve the need for a “no-brainer” investment uniquely well, and, in many cases, an index fund is the default fund of choice by plan administrators, who see it as the fund of least risk to themselves as fiduciaries.

What’s more, there is also evidence that the millennial generation has more of a predisposition toward passive investing than preceding generations. This may be because of a heightened sensitivity to fees, mixed with a touch of anti-Wall Street sentiment.

The performance numbers have long favored the passive fund in a side-by-side comparison, particularly when commissions and transactions costs were sky high. But investor behavioral biases and perceptions kept the active management allure alive. Though active mutual funds are steadily losing assets to passive index funds, active management is hardly circling the drain. There is plenty of evidence that active managers use passive funds or ETFs in sophisticated rules-based strategies that focus more on allocation among multiple asset classes (and geographies) and sector timing than pure stock picking. These strategies also can have the ability to ratchet up or down their market exposure depending on current trends, as well as further risk management through hedges or inverse positions.

Additionally, investor behavior is not solely geared to financial performance. People also use their money to express their views: to make statements on social issues, support causes they like, reward ingenuity or innovation, bolster their local economy, and even to approve or disapprove of a CEO’s behavior. Active managers are in a much better position to help investors express their views than any broad index fund.

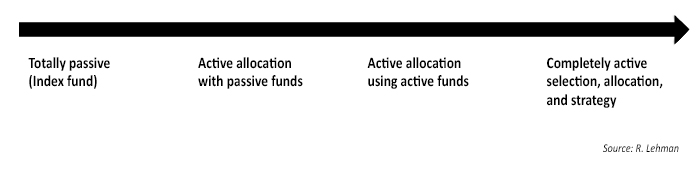

Behavior isn’t binary, and neither is management

Lastly, the comparison of an index fund to an actively managed mutual fund (let alone a portfolio of active strategies) assumes a binary set of options that simply do not meld with investor behavior, which lies in different places along an ever-widening spectrum defined by the risk posture of the client, the investing environment, the client’s time horizon, and their need for expression, among other variables. Active managers today can offer investors a multiple-asset-class investment strategy that may well use passive components, but which can be centrally driven by where the client needs to be on this spectrum.

Active Management Spectrum

From this perspective, the active versus passive debate may not even be a debate anymore. Instead, the question for investors and their financial advisors is to determine where they best fit on the active management spectrum and what degree of active management is optimal to their needs.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Proactive Advisor Magazine. These opinions are presented for educational purposes only.

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.