Two-thirds of adults struggle with retirement savings: An opportunity for advisors?

Two-thirds of adults struggle with retirement savings: An opportunity for advisors?

Several factors combine to stack the odds against people saving enough for retirement. Some advisors recognize this as an opportunity—not just to help people but also to grow their business.

It may be no surprise that many people aren’t saving enough for retirement, but the extent of the problem is staggering—and it has worsened in recent years.

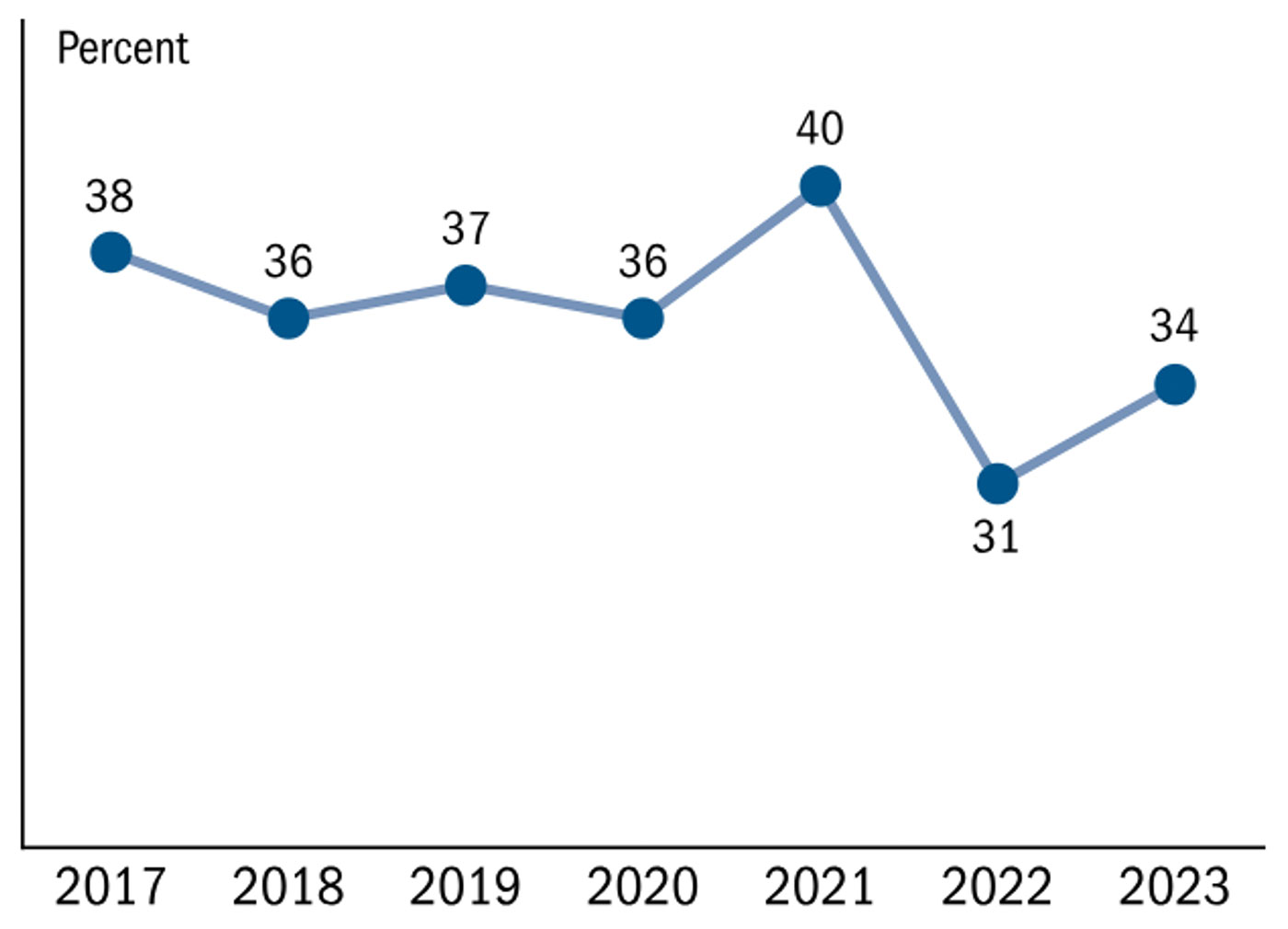

According to the Federal Reserve’s 2024 report on the “Economic Well-Being of U.S. Households,” only 34% of non-retired adults believed their retirement savings plan were on track in 2023—an improvement from the previous year but well below the 40% reported in 2021. That means about two-thirds of people feel they are not on track.

PERCENTAGE OF RESPONDENTS WHO VIEW THEIR RETIREMENT SAVINGS AS BEING ON TRACK

Source: Federal Reserve

Understanding the obstacles to retirement savings

It’s easy to stereotype those who are off track as people who don’t earn enough, spend too much, or are just irresponsible about saving. As a result, advisors may perceive little potential in this group as well.

In reality, lack of money is just one of many reasons people under-save. Advisors who recognize this can tap into a large and often overlooked segment. The barriers to saving generally fall into three categories:

- Financial literacy: Many people lack an understanding of basic financial concepts like inflation, tax-advantaged savings programs, compounding, annuitization, and investing. Even those with some general knowledge often struggle to make the necessary assumptions about their longevity, retirement costs, interest rates, and expected returns.

Research shows that those with a written financial plan are significantly more confident about their retirement and save more money than those without one. Additionally, Vanguard research indicates that working with a financial advisor could result in as much as 100% greater compounded investment returns over 25 years compared to self-directed investing.

However, many people feel embarrassed about their lack of financial knowledge and are intimidated by the idea of consulting a financial advisor. Some fear their assets are too small for an advisor to take them seriously or worry about being turned away.

Past market downturns can also play a role. Many people, regardless of education level, remain scarred by the Great Recession and its accompanying 50%-plus equity-market losses. This experience has made some hesitant to contribute to employer-sponsored retirement savings plans, mistakenly believing they only offer stock investments. According to the North American Securities Administrators Association (NASAA), this hesitancy is particularly pronounced among millennials, who came of age during the Great Recession, may carry high student debt, and faced uncertain job and salary prospects early in their careers. NASAA notes, “It’s easy to see why some (not all) might be nervous about putting their hard earned savings into an investment that carries any degree of risk.”

- Behavioral biases: Even those with sufficient knowledge about retirement saving can face a gauntlet of behavioral biases like procrastination, present bias (spend now, worry later), aging denial, and overconfidence (thinking they can build enough wealth through other means)—just to name a few.

Fear of social embarrassment can cause us to bend to peer pressures to dine out, travel, attend events, or incur other discretionary expenses—stretching already tight budgets. Anchoring causes people to fixate on their take-home pay as the number they have to spend each month.

That drives decisions around mortgages, rent, car payments, social and entertainment costs, and other monthly expenses, but usually gives little consideration to unexpected expenses like car repair, unplanned travel, or escalating food and energy costs, much less retirement savings.

- Circumstances: Personal situations, such as unexpected illness or job loss, can create financial strain. Those who live paycheck to paycheck may view retirement savings as an unaffordable luxury.

In all three cases, people will be hard-pressed to change their behavior—which is why the numbers are so bad in the first place. Advisors have the tools and expertise to help, yet they often see little financial incentive in servicing this audience.

Are they missing something?

In some cases, yes. Those without the means to save are only a portion of the non-saver group. Many who are not financially savvy or struggle with behavioral biases could benefit greatly from working with an advisor. That represents opportunity, which I believe can be found in each of the three categories above.

Increasing financial literacy

Some advisors are already addressing financial literacy gaps by volunteering with nonprofits to provide financial education, offering seminars or classes at local schools, hosting podcasts, and more. While much of this work is pro bono, there are also ways to offer financial and retirement planning at reasonable fixed or hourly rates.

Efforts to improve financial literacy may be best approached outside of your existing practice activities. Ric Edelman, who built and later sold Edelman Financial Engines—one of the most successful financial advisory firms in the U.S.—launched his career with a weekly call-in radio show answering financial questions. This platform connected him with a huge audience of non-investors who nonetheless had assets.

Many advisors interviewed by Proactive Advisor Magazine have followed Edelman’s model on a smaller scale, using podcasts or local radio shows to educate the public while building brand recognition. Some report that new inquiries have come in from listeners who later schedule complimentary financial assessments.

Resourceful advisors also look to partner with retirement services providers—such as recordkeepers, banks, and mutual fund companies—to educate 401(k) plan participants. Plan sponsors, wary of crossing into investment advice, have historically limited the education they provide. While they avoid endorsing specific advisors, they often welcome trusted professionals who can offer unbiased retirement-planning expertise—particularly in the nonprofit and educational sectors—without heavy sales pressure.

Some advisors have made this a mainstay of their prospecting efforts, offering free consultations to plan participants on broader financial planning. Even when these partnerships offer no direct compensation, they often lead to valuable networking opportunities; referrals; and connections to businesses, relatives, and company executives.

For example, one advisor I knew hosted monthly off-site “brown bag” retirement lunches for employees of the local utility company. While the company didn’t endorse specific advisors, it had no problem with his free educational lunches—and because he thoroughly understood the company’s retirement plan, employees saw him as a valued resource. It seemed like every month he was signing new rollover accounts—some in the seven figures.

Advisors who expand their referral networks can help hesitant prospects see the value of professional guidance, including assistance with sometimes daunting 401(k) or 403(b) investment options. For those who are wary of investment losses—or simply like the appeal of professional investment management for their retirement plan—an increasing number of advisors are helping them set up self-directed brokerage accounts within their retirement plans, allowing for broad retirement savings guidance and professional investment management from third parties.

While some advisors may not view financial literacy as a major role, many clients expect some level of education from their advisors. Some seek only the basics, while others see education as a primary benefit of an advisory relationship. Advisors should assume clients want to learn but also tailor their approach to each individual’s learning style and goals.

Overcoming behavioral obstacles

Advisors knowledgeable in behavioral finance can help clients overcome biases that hinder the implementation of effective financial strategies. However, because investors are often unaware of their biases, they typically don’t seek help to overcome them.

This is where advisors need to get creative—finding ways to connect with people who aren’t saving enough for retirement that overcome both a prospect’s bias against seeking help and their own bias about offering help to an audience perceived to lack potential.

Traditional seminars can be effective, but prospects may avoid them if they seem like sales pitches or if they fear revealing their lack of knowledge in public.

A twist on the seminar idea that I’ve seen work is an open house—a casual social event where existing clients bring guests. These events feature optional, informal talks on financial topics, allowing attendees to come and go freely while mingling with advisors and clients. The unstructured nature of the event tends to reduce intimidation.

Some advisors take this concept further, organizing themed events like wine tastings, cooking lessons from a local chef, excursions to sporting events or concerts—even private hot air balloon events or surfing lessons. Others add a charitable element, such as coat drives at holiday gatherings. These settings make advisors more approachable, helping to break down psychological obstacles to seeking financial guidance.

Addressing financial barriers

Personal circumstances can definitely hinder many people from saving for retirement, but some may assume their situation is impossible to overcome when options do exist.

Many believe they “can’t afford an advisor” or “don’t have the money to warrant one,” sometimes because some advisors set minimum investment requirements. While advisors are free to decide who they will work with, those who help clients early in their financial journey may build long-term relationships that lead to dividends down the road. Every client is a networking opportunity, and you never know who they might lead you to.

For prospects who aren’t saving because they lack access to a workplace retirement plan, an advisor can introduce alternatives like IRAs. Even better, the advisor can go speak to the company and help them set up a plan.

If the prospect has a plan but doesn’t participate, that too presents an opportunity to speak to the company. Other employees may also not be participating, and the company might welcome some help in educating them.

A growing trend in the industry addresses the issue of cultivating clients who may have little or no investable assets through relatively low-cost subscription-based planning services. One advisor, who works for the investment division of a large credit union, charges a reasonable monthly fee to guide members on fundamental financial issues.

He says, “I provide one-on-one financial guidance on creating budgets, establishing banking relationships, reviewing loans, taking advantage of employer matching programs, and building credit or paying down debt as needed. … Subscribers are guided through key money milestones toward financial freedom, from an initial assessment to creating next steps. Monthly accountability calls and quarterly action items ensure consistent progress.”

Over time, he sees a good portion of these subscription clients being able to build their assets and transitioning to a fuller advisory relationship.

How can advisors help, and what’s in it for them if they do?

While prospecting among wealthier clients is appealing, the unadvised audience and those who cannot comfortably retire represent a vast market.

Exploring that opportunity is not for all advisors, but it also doesn’t require a full-time commitment. It can be addressed with modest efforts that are separate from an advisor’s broader practice.

Though helping people save more for retirement has less immediate financial reward than managing existing wealth, it may open doors to setting up retirement plans with employers—which then provides access to employees, company executives, plan administrators, and investment firms. Advisors who take a long-term perspective may find that serving this overlooked market isn’t just a way to give back—it’s also a smart business strategy.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and the sources cited and do not necessarily represent the views of Proactive Advisor Magazine. This material is presented for educational purposes only.

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.

RECENT POSTS