10 destructive behaviors of ‘emotional investors’

10 destructive behaviors of ‘emotional investors’

Behavioral biases exist and subconsciously influence us, many times at a significant cost. The good news is that there are tools that financial advisors can use to identify and reduce the impact of biases—both for themselves and for their clients.

Financial advisors and their investor clients have faced a period of huge market swings in 2020 and great investment uncertainty in the fallout of the COVID-19 pandemic. (Not to mention the emotional burden of concern for loved ones, for their safety, and for those families around the world who have lost a cherished family member.)

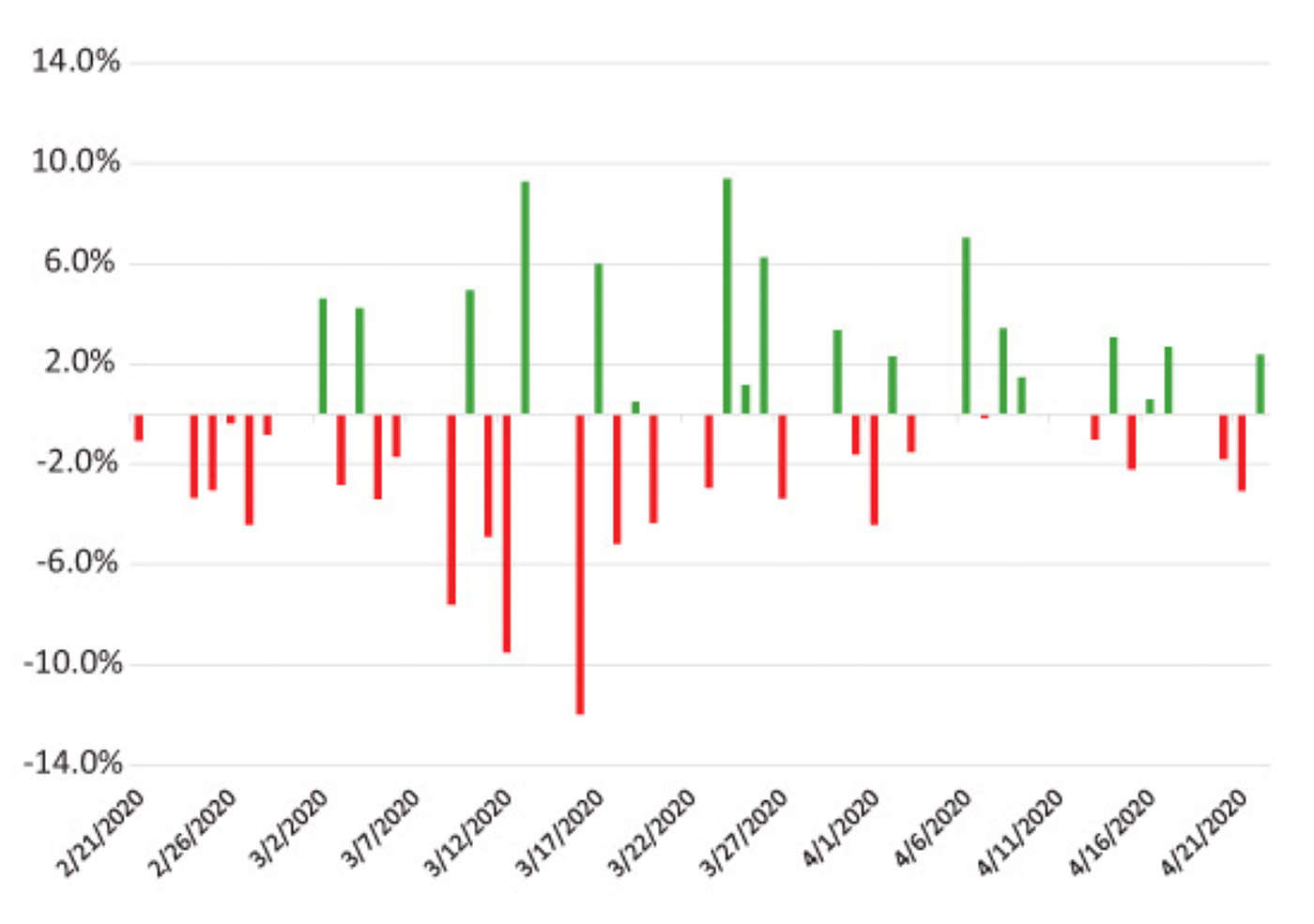

The American Association of Individual Investors (AAII) developed Figure 1, showing the market’s roller-coaster ride for the period from late February to late April 2020. The organization noted, going back to 2011, “the largest number of days in a single calendar year with a closing change in the S&P 500 index of greater or less than 2% was 35—for the year of 2011. … We’ve already experienced 30 such days for 2020.”

Source: American Association of Individual Investors (AAII), data through 4/22/2020

With the CBOE Volatility Index (VIX) hitting elevated levels not seen since the financial crisis, and major U.S. equity indexes rapidly entering bear market territory, Q1 2020 made managing risk—and investment expectations—a more urgent consideration for financial advisors and their clients.

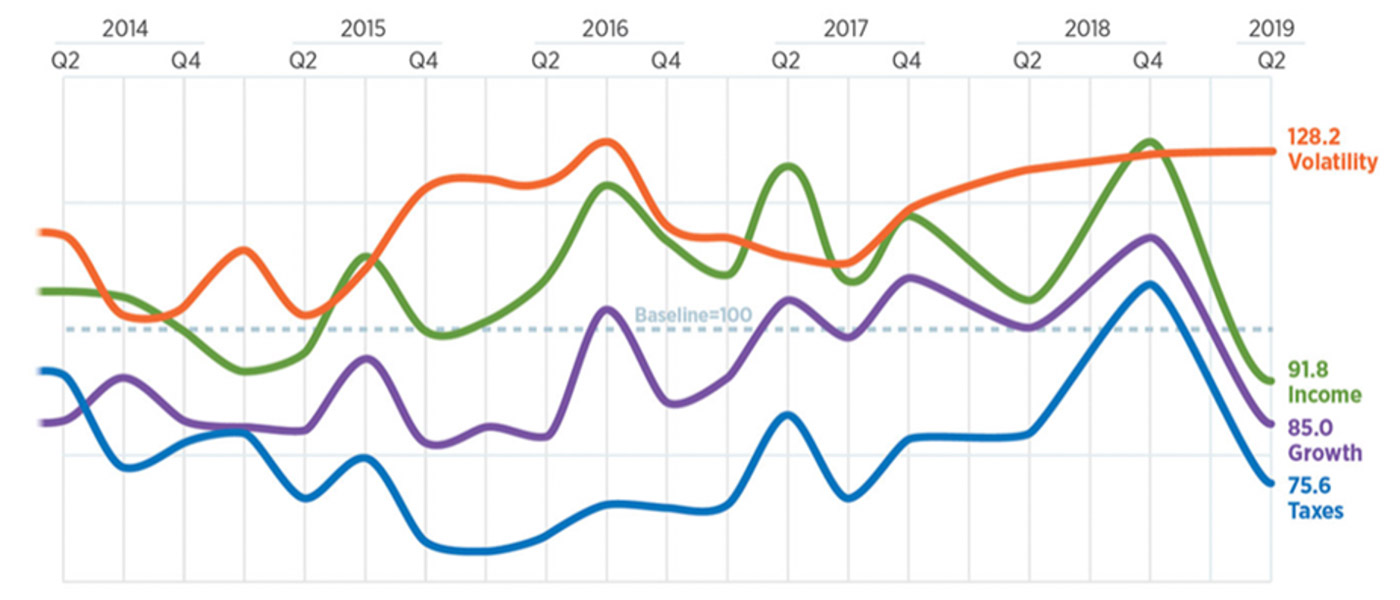

However, this was really nothing new. For some time, a top concern of financial advisors of all stripes has been the management of volatility. This became particularly pronounced after the market drawdown of almost 20% in Q4 2018.

Source: Eaton Vance Advisor Top-of-Mind Index (ATOMIX), spring 2019

While this study has not yet been updated for 2020, there is little doubt that the results will show that “managing volatility for clients” has become of even greater concern for financial advisors. Eaton Vance wrote in an April 23, 2020, post, “Market participants will attempt to reconcile the sharp recent market rally with what looks like to be a fairly prolonged extended economic contraction and slow recovery in the United States, so we would expect volatility to continue.”

In a volatile market environment, investors become even more prone to emotional investment decision-making, often at great cost to their long-term investment health.

Another post from Eaton Vance’s advisory blog talks about the “siren song” that drives investors to panic selling and then chasing returns for fear of missing out on a market recovery, both actions usually coming at exactly the wrong time. Investors, the firm says, “validate their desire by looking at data from recent bear markets without understanding the ways this bear market is unique: It came at the end of the longest bull market in modern history, and it’s being driven by an exogenous shock.”

Jay Mooreland, MS, CFP, is an expert in behavioral finance and coaching financial advisors. His objective is to help advisors enhance value in their advisory relationships—guiding clients via behavioral finance principles to make better financial decisions.

Mr. Mooreland founded The Behavioral Finance Network and has created several behavioral applications for advisors’ practices, as well as offering valuable coaching programs for advisors. A sought-after speaker on the topic of investor behavior, he has published several articles in industry journals and is the author of “The Emotional Investor: How Biases Influence Our Investment Decisions…And What You Can Do About It.” His website, The Emotional Investor, and his blog offer frequent observations on behavioral finance in the context of the current market environment.

Mooreland’s 2015 book, “The Emotional Investor,” came about in part because of the 2007–2009 financial and economic collapse around the globe.

It is particularly relevant today.

In the introduction to the book, he shares his story of disappointment, self-discovery, and the search for solutions to some of the behavioral issues that plague retail investors and financial advisors—both in times of crisis and in roaring bull markets:

“The crisis was the financial meltdown of 2008. I didn’t expect it, and like many people was not ready for it. But I wasn’t just an investor; I was an investment advisor. I was the person people relied on to plan out their financial future and select investments to help them reach their financial goals. Investors that entrusted me with their money had prudent strategies and maintained diversified portfolios. But the crisis was severe, and most asset classes experienced significant losses, even the diversified portfolios. …

“As I sorted through the events, I realized I could do nothing about the past, so I had to prepare for the future. … So I decided to return to school.”

In graduate school he focused heavily on behavioral finance, seeking to better understand emotional influences on investors. He says, “That’s what this book is all about: learning to subdue emotional influences and make more deliberate and thoughtful financial decisions.”

“I directed a significant percentage of research for my thesis on what are referred to as ‘behavioral biases,’ ‘behavioral tendencies,’ or ‘preferences’ that influence our decisions. And most of these influences are subconscious, meaning we are not aware of their influence. … I’m more of a realist than I am a theorist. Behavioral economics, also known as behavioral finance, highlights the significance of living in reality. It’s important to recognize who you are today and to make decisions about becoming better down the road.”

In “The Emotional Investor,” Mooreland cites 10 key behavioral influences that lead many people to consistently poor investment decision-making:

- “We are physiologically hardwired to make hasty decisions without much thought.

- Market volatility can cause us to become emotional and lose our sense of where we are and where we want to go.

- We like instant feedback (gratification), which influences us to act based on short-term outcomes.

- The aversion to uncertainty makes us seek some certainty, even if it is just an illusion—such as with market predictions.

- We tend to micromanage our investments because it makes us feel in control.

- The media often causes us to focus on short-term events and makes it difficult to differentiate important news from noise.

- We believe we are better at investing than we really are.

- Our decisions are often influenced by reference points such as our profit/loss on an investment and past performance.

- We detest loss, and may make unwise decisions in an attempt to avoid loss.

- Our perception can be faulty.”

Mooreland’s comprehensive road map for investor improvement focuses on three key points:

- Recognize and understand behavioral pitfalls and consciously acknowledge (and try to avoid) their influence in future investment decision-making.

- Don’t be afraid to embrace and learn from mistakes of the past. Be disciplined in avoiding future mistakes of process. However, recognize that even the best process will not always be successful, but long-term discipline in sticking with a sound process usually will.

- Seek the guidance of a qualified investment “trainer,” a financial advisor or wealth manager. Recognize that much of their value will be in behavioral coaching and their advocacy for sticking with the objectives of a well-defined financial and investment plan.

Mooreland says,

“We need to do what we’ve been told to do for years: Create an investment plan and stick to it. We have heard it over and over, but now we understand why. We need a plan because it will provide the framework to help us overcome our natural tendencies to do the wrong thing at the wrong time.”

On the value of financial advisors, Mooreland writes,

“A personal financial trainer should teach you investment truths and important principles to successful investing. They help you learn to filter the noise of the media and deal with market volatility. And when things get tough, they are there to encourage you to keep at it. They are there to help you stay disciplined to your plan so you can reach your goals. …

“Advisors that ‘get’ the behavioral aspect of investing are much more valuable than those who don’t. Vanguard recently broke down the value of a good, qualified financial advisor. Their analysis shows that an advisor’s value can add more than 2 percent per year to return. And you know what the biggest factor is in the added value? Behavioral coaching.”

He adds,

“Many investors spend the majority of their time considering factors that are beyond their control. We constantly wonder what the market is going to do, what sectors will outperform, where interest rates are heading, and what policy changes government may make.

“Yet we spend very little time thinking about issues over which we have complete control—things like our investment process and plan, and how we are going to react to future market events.

“Jason Zweig, a columnist for The Wall Street Journal and author, wrote this profoundly simple truth (mirroring the words of Benjamin Graham): ‘Investing intelligently is about controlling the controllable.’”

Mooreland concludes, “Emotional investing may feel good, but thoughtful investing is good.”

***

Editor’s note: Advisors and their clients would both benefit from reading “The Emotional Investor,” available at Amazon. Financial advisors may want to explore the programs Mr. Mooreland offers at The Behavioral Finance Network.

David Wismer is editor of Proactive Advisor Magazine. Mr. Wismer has deep experience in the communications field and content/editorial development. He has worked across many financial-services categories, including asset management, banking, insurance, financial media, exchange-traded products, and wealth management.

David Wismer is editor of Proactive Advisor Magazine. Mr. Wismer has deep experience in the communications field and content/editorial development. He has worked across many financial-services categories, including asset management, banking, insurance, financial media, exchange-traded products, and wealth management.