The coming transformation of technical analysis

The coming transformation of technical analysis

While technical analysis has its roots in practices thousands of years old, advances in technology, behavioral psychology, and artificial intelligence will lead the next transformation of the discipline.

Origins of technical analysis

Technical analysis (TA) on markets and securities might not claim as many professional practitioners as fundamental analysis, but it has been around a heck of a lot longer and has a deep following among both market pros and individual investors.

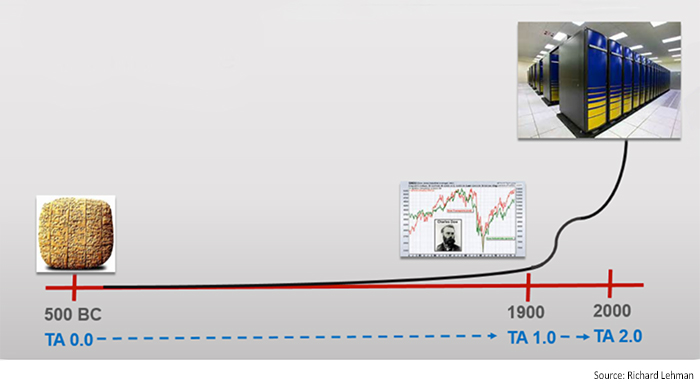

The origins of TA go back as far as 500 B.C., according to “The Evolution of Technical Analysis” by Andrew Lo and Jasmina Hasanhodzic. Naturally, there were no publicly owned companies back then, but there were commodities such as wool, barley, and dates. The Babylonians kept records of the prices on these items and used them to predict future movements. They accumulated an astonishing 400 years of data, a feat modern price history on stocks doesn’t come close to matching. We might never have known this if not for the Babylonians, who literally set their records in stone!

Our more modern and far more visual approach to technical analysis emerged at the turn of the 19th century when Charles Dow began publishing stock price data in his newly established Wall Street Journal. Dow and his successor, William Peter Hamilton, brought a measure of scientific legitimacy to price analysis of stocks, raising the stature of technical analysis from practice to profession.

Dow’s work laid the foundation for market technicians over the ensuing decades who developed a wide array of technical indicators, sentiment indexes, moving averages, bands, waves, phases, cycles, patterns, and other techniques, all designed to extract clues to future movements through insights gained from previous price data. Technical analysis is still a widely used discipline in the commodities world, and, increasingly, many stock analysts and portfolio managers who ascribe to fundamental analysis for their primary long-term investment outlook turn to technical analysis for clues to shorter-term market trends and dynamics.

While Dow’s work became widely known and followed, professional stock analysts favored the fundamental work of Benjamin Graham and David Dodd with greater dedication following the publication of their seminal book “Security Analysis” in 1934. Part of the reason technical analysis drew less commitment from professional analysts may be because the discipline encompassed many individual techniques, while Graham and Dodd’s approach represented a more singular approach. In addition, the techniques espoused by self-proclaimed market technicians included questionable practices, some of which relied on nonfinancial criteria such as astrological observations. The association with such practices tarnished the image of technical analysis enough to cast a pall over the entire discipline for many professionals. Some of that negative perception persists today, as evidenced by such articles as “Is Technical Analysis Mere Hocus Pocus?”

While Dow’s work became widely known and followed, professional stock analysts favored the fundamental work of Benjamin Graham and David Dodd with greater dedication following the publication of their seminal book “Security Analysis” in 1934. Part of the reason technical analysis drew less commitment from professional analysts may be because the discipline encompassed many individual techniques, while Graham and Dodd’s approach represented a more singular approach. In addition, the techniques espoused by self-proclaimed market technicians included questionable practices, some of which relied on nonfinancial criteria such as astrological observations. The association with such practices tarnished the image of technical analysis enough to cast a pall over the entire discipline for many professionals. Some of that negative perception persists today, as evidenced by such articles as “Is Technical Analysis Mere Hocus Pocus?”

Notwithstanding the questionable reputation of certain specific techniques, many individual investors—who don’t have the luxury of employing a team of highly paid analysts to help them with the fundamentals—have been more likely to employ some form of technical analysis. And organizations geared toward exploring sophisticated techniques for professionals, such as the Chartered Market Technicians Association, have thrived. The CMT Association (formerly known as the Market Technicians Association) is a long-standing and highly respected not-for-profit member association of more than 4,500 investment professionals in 85 countries.

As a result, charting the markets and following various price indicators has become the pastime of an untold number of individual investors and professionals searching for perspectives on the trends in the markets. Technical analysis complements their attempts to divine whether their stocks, funds, ETFs, or other holdings are fundamentally under- or overvalued based on exhaustive analysis of factors such as projected earnings, competitive positioning, profit margins, and debt structure.

The current transformation in TA

Today, technical analysis enjoys a robust international following and is supported by a professional industry certification from the CMT Association. What’s more, technology has blessed technicians with access to huge arrays of price data, flexible and virtually instantaneous charting software, and access to a long list of technical indicators. But several factors have the potential to change the nature of technical analysis, transforming the discipline as much in the future as when Dow published the first price charts. These factors include the leap in computing power, enhanced data mining, the rise of artificial intelligence, advancements in behavioral finance, and public and professional perception of TA.

TECHNICAL ANALYSIS TIMELINE

As the rising tide of computing technology lifted all data ships over the last several decades, technical analysis gained handsomely from increasing computing power, enhanced visualization software, and the integration of real-time data. This was heaven compared to only a few decades ago when charts were still published on paper and mailed to you weekly. But with the realization that computers could calculate all this data rapidly and present it to us so effectively came the logical next step of programming the computers to scour the charts for us, interpret the results or identify prescribed trade setups, and then even execute the trade. Such activities are already well in place at financial institutions.

Much of the more recent advancements in IT are now being driven by the introduction of machine learning and artificial intelligence. Computers could always dwarf our capabilities to analyze data, but now they are being taught to think and learn. This represents a significant leap forward for the machines, which already had about as much of an advantage over humans as humans have over slugs. A number of prominent hedge funds—the pioneers of almost everything new in the investing realm—have already embraced technology in a big way, retooling and restaffing over the last decade to focus on exploiting short-term market inefficiencies rather than attempting to outperform the market through more efficacious stock-picking. Since short-term inefficiencies generally have little at all to do with fundamentals, the hedge fund community is relying more on technical forms of analysis than ever before, and their computers are conducting most of that analysis all by themselves. They are even being taught to recognize patterns, so there is almost no technical analysis that couldn’t be performed by a robotic trader these days.

Many of these inefficiencies are now being traced to behavioral factors, which represent the second phenomenon affecting technical analysis today. As with technology, behavioral finance is a double-edged sword for technical analysis. In some ways, behavioral studies are providing, for the first time, an underlying rationale for why price varies as it does. For example, prices tend to trend and then to revert back to the mean over time, illustrating the effects of herding, anchoring, and momentum. This is a very promising development for technical analysis, as it is finally putting some scientific rationale into the notion that past prices can indeed offer clues to future movements and direction.

While behavior is not an exact science like physics, and it is often challenging to quantify behavioral effects at all due to their complexity, behavioral theory is widely accepted as a legitimate science and is now the subject of frequent experiments that are explaining underlying market movements. Consumer behavior is also not an exact science, but through decades of experience and testing, the retail and advertising industries have been able to get extremely accurate in predicting consumer behavior under certain circumstances. Thus, it is not a big leap to assume that behavioral finance will provide similar insights for the investment industry over time as well. In other words, behavioral factors are lending an underlying credence to technical analysis that was previously absent in scientific terms.

In addition, though, there is another aspect of behavioral revelations that also impacts technical analysis. Many TA methodologies are highly visual in nature, centering in one way or another on price charts from which conclusions or judgments about market direction are drawn. Behavioral science tells us, however, that the “intuitive” skills we think we have with regard to identifying patterns or trends in data series are flawed and frequently subject to irrelevant factors. It turns out that humans are endowed with an evolutionary skill at pattern recognition that was evidently useful to survival on the savanna. But that pattern-recognition skill favors speed over accuracy and thus becomes a hindrance in examining highly quantitative phenomena such as price charts.

Behavioral factors are lending an underlying credence to technical analysis that was previously absent in scientific terms.

We tend to employ shortcuts, jump to unjustified conclusions, and take inappropriate actions as a result. What’s worse is that we don’t see these weaknesses in ourselves. Instead, we tend to believe that our ability to see visual patterns from data sets represents an admirable skill, when in reality, it is a liability because it leads us to take premature action that is often not justified by the available data. As an example, a chart watcher might spot a particular pattern that occurred in the equity markets on the last four dates when the Fed raised interest rates. It is subconsciously tempting to feel confident that the pattern will repeat because it did in all four observations. But for a statistical analysis to generate 80%–90% confidence in such a conclusion, we should be using upward of about 200 observations. In short, humans are simply not well-equipped to conduct effective visual data analysis.

The third major influence on technical analysis is the degree of skepticism still found regarding the discipline. While there have been numerous books on the subject of TA in different forms, there has never been a universally accepted definition for what forms of TA are considered valid or which have been proven to work well in practice. This is partly because so many different forms and techniques of TA exist and because few forms are used in total isolation, making it difficult to provide a clean, verifiable track record of their success.

The absence of such validation has always tended to fuel a level of skepticism, particularly among classical stock analysts. Unfortunately, this skepticism has permeated into the legal and regulatory system, where the thinking is very binary and fundamental analysis reigns supreme under the “prudent man” rule, which is the ultimate arbiter of liability. An investment advisor who is sued by a client for poor investment performance, for example, can claim a legitimate defense by saying that fundamental evaluations were performed on a portfolio of stocks prior to the 2008 financial crisis and that no amount of analysis could have predicted the extent of the declines that ensued. On the other hand, a defense that relies on having constructed a portfolio using only technical factors such as cycles and sentiment indicators would not likely pass as being prudent enough in the eyes of a judge or an arbitrator. Until this myopia in the legal system is alleviated, professional investment managers will always lean toward taking the defensible position and using fundamentals to justify their investment actions.

What does this mean for the future of TA?

As both a long-standing technician and a professor of behavioral science, I see good reasons to expect that the legitimacy of both TA and behavioral finance will increase as more and more technical indicators are tied to behavioral characteristics. However, while this exploration should hopefully provide a lift to technical analysis overall, it will tend to support the legitimacy of some TA techniques and not others. This may be a necessary distinction to make in order to define TA in more narrow terms for greater visibility and wider professional acceptance.

As for technology, it would be naïve to assume that technical analysis would not eventually become a highly automated practice, as it is already on that path. In fact, analysis tasks such as pattern recognition are expected to be early applications of quantum computing, which is expected to be the next big wave in computing technology. New analytical techniques and more sophisticated algorithm-based trading models will initially be dominated by the players with the largest computers and the most people to program them. But, as with all things technology-related, it should eventually migrate down to desktop applications, where it can be used by a wide universe of both professional and self-directed investors. This will most likely represent a huge leap forward that leads to the next transformation of technical analysis.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Proactive Advisor Magazine. These opinions are presented for educational purposes only.

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.