Mutt vs. purebred: How should you invest?

Can lessons learned from our canine friends provide a better understanding of the characteristics of effective portfolio diversification?

I’ve had a dog as a pet since I was about 6 years old. My first dog was called “Shiner.” You can guess why. Most of our family dogs (which number about a dozen by now) have been, like Shiner, mutts.

I remember we had two purebreds—a golden retriever (Snuffy) and a black Labrador (Brandy). They were great dogs. We raised both of our boys with them. They could not have been better companions, trusted friends; they were so gentle with the boys. We loved them both.

Unfortunately, Snuffy, like an awful lot of golden retrievers, died early of cancer. Brandy, as was the case for most of her breed, suffered from hip dysplasia and skin allergies. By contrast, all of our many mutts lived longer, healthier lives and basically died of old age.

It’s an age-old dispute: What’s better, a mutt or a purebred? The argument for mutts that I hear most often mirrors my experience: Mutts are much less susceptible to genetic disorders.

A 2013 study conducted at UC Davis that examined the vet records of more than 27,000 dogs spanning a 15-year period provided support for this argument. While it was found that purebreds had a greater incidence of 10 different genetic diseases, mutts only seemed predisposed to one.

As the Animal League of America states on its website, “When you adopt a Mutt…, you benefit from the combined traits of two or more breeds.”

But purebreds are not without their advantages. Chief among them is that they are more predictable. You know mostly what you’ve got when you get them. That’s why they are great as both show dogs and work dogs.

Does the mutt vs. purebred “argument” have an analogy in investing?

In investing, I think of the commonly referenced asset-class indexes as purebreds—you know, the stock indexes such as the S&P 500 and the NASDAQ Composite, bonds represented by the Barclays Aggregate Bond Index, and commodity indexes such as those from Goldman Sachs. They are predictable in a sense. They have long histories, and they basically behave the same way at different points of the economic cycle.

Like purebreds, single asset classes are known for their good and bad traits. They, too, have their genetic defects, the principle one being that they are all volatile when owned individually. Each goes through its own periods of severe losses.

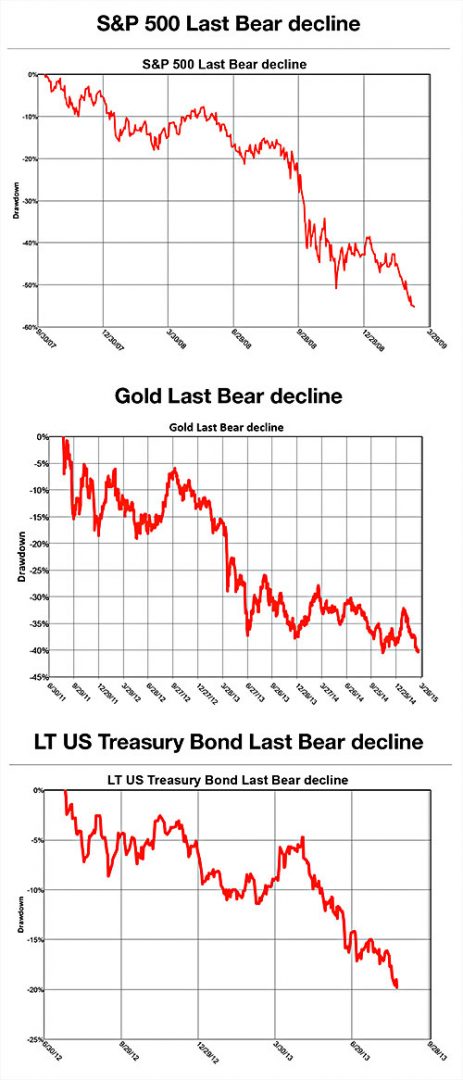

Here’s a snapshot of three popular asset classes, each going through an actual crisis period. These are not isolated occurrences. Each has had its own “crash” many times over. In each, a $100,000 investment can easily lose $50,000 in a very short time.

FIGURE 1: EXAMPLES OF ASSET CLASS “CRASHES”

The most common way of dealing with this danger to your clients’ financial health is diversification. Each of the asset classes in the preceding charts has grown in value over the long run. The problem is that all of them go through these sudden slides in value. On the positive side, the downdrafts in each asset class tend to happen at different points in time from each other. One solution, then, is to invest in all three.

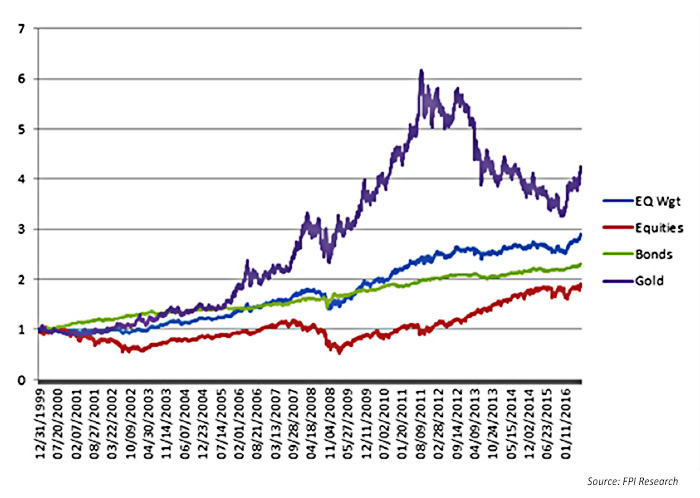

That’s an example of diversification. The following chart compares the results of a portfolio equally weighted (and rebalanced quarterly) between stocks, bonds, and gold with the results of each of the asset classes on their own.

FIGURE 2: DIVERSIFIED PORTFOLIO VS. INDIVIDUAL ASSET CLASSES THIS CENTURY

(AS OF JAN. 2016)

The benefits (and limitations) of diversification

The diversified portfolio (the blue line labeled “EQ Wgt” in Figure 2) ends up outperforming two of the three indexes; however, it is not close to the explosive growth of gold, even after its 2011–15 tumble. But note that when gold fell during that period, the diversified portfolio kept rising. Similarly, when stocks slid in 2002–4 and 2007–8, the portfolio’s declines were more moderate, and its recovery to new highs each time was much quicker. Even when bonds fell in 2012–13, the diversified portfolio flattened out and began ascending sooner.

I tend to think of a diversified portfolio as a mixed-breed mutt who benefits “from the combined traits of two or more breeds.” The performance tends to be more robust and healthy. It is not as likely to fall victim to the defects of historical lineage like the purebred indexes.

A diversified portfolio is definitely not a “show dog.” While it smooths out the indexes’ rough spots, it can only produce average results (the average of returns of the investments used). It’s being adopted not for “Best in Show” possibilities but rather to deliver good results without dire threats to its financial health.

As a result, the diversified portfolio will never do as well as or better when the best-performing investment is doing its best—just as a mutt will never win the Westminster Kennel Club Dog Show. But, just as the mutt provides great comfort when a problem surfaces at home, a diversified portfolio should outperform when a financial crisis occurs.

What are the characteristics of effective portfolio diversification?

To qualify as diversified, an investment portfolio should meet two conditions: First, it should hold multiple investments in different asset classes. Second, the investments should display their downside volatility at different points in time.

The first is relatively easy to accomplish. Just as there are more than 400 canine breeds, there are also hundreds of different asset classes in which you can invest. But which ones are best for a truly diversified portfolio?

That’s where the second criterion comes in. The investments chosen need to respond differently to diverse economic stimuli. When you track their daily or weekly movements, they should often zig when the others zag.

Finding these “uncorrelated” asset classes is the most difficult task, and the one upon which most investors stumble. Lured by historical returns—whether compiled over last year, the last three years, or the last 20 years—investors tend to pick the top performers on a return basis when they select investments for their portfolios. Instead, they should look at how they perform in all types of markets individually—bull, bear, and sideways—and make sure that they include top performers in each type.

Similarly, they need to check the correlation statistic for each of the investments—not only against the S&P 500, but also against each other. Correlation measures the extent to which investments move in unison. To create a more robust portfolio, you want to avoid investments that are too similar in their movements.

Finally, when you check on the individual components of your portfolio, you should not recoil when you see a loss in a component or two. You wouldn’t do that with a Lab who came down with hip dysplasia. Rather, if the investment was put in to diversify the portfolio, congratulate yourself on being prepared for the next market cycle, which is not likely to be the same as the present one, which may be driving your other investments higher.

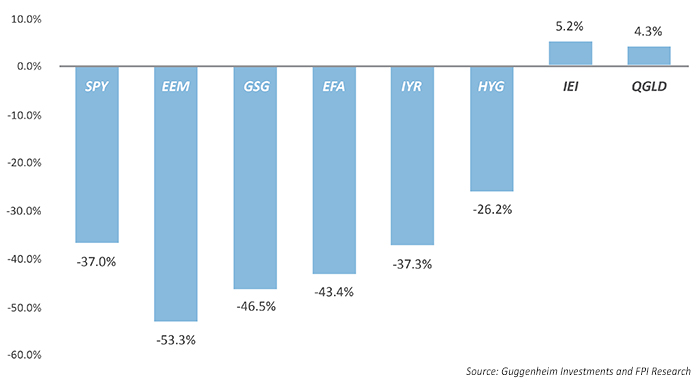

As I always say, “If all of your investments are going up, you are not truly diversified, and you may be in for a rude awakening.” Check out what happened to many of the bull-market favorites when the 2008 crash occurred in stocks. All of these asset classes were touted as portfolio diversifiers, yet only gold and bonds actually delivered.

FIGURE 3: ASSET-CLASS PERFORMANCE DURING 2008

It turned out that only gold and bonds were true diversifiers, which brings me to my concern today. Over the last 30 years, bonds have been one of the two go-to investments for times of crisis. Few other asset classes have delivered the noncorrelation necessary to offset the risk in the stock market during financial calamities.

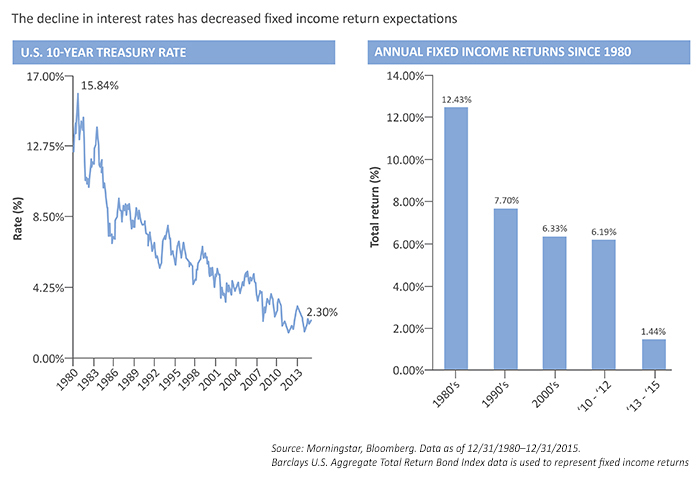

FIGURE 4: ARE INVESTMENT GRADE BONDS STILL THE ANSWER?

Yet as the chart shows, interest rates have fallen to the extent that there is less room for them to fall further. That’s a problem because bonds go up in price when interest rates go down. If there is little room for further declines in interest rates, bonds are going to have a tough time rallying when a future financial crisis hits.

Sure, the Federal Reserve wants to raise rates, and you can see why. But since Brexit, most commentators believe that the Federal Reserve can have little effect when the rest of the world keeps lowering their rates, even to the point where the yield is negative.

Most financial planners and asset managers have been turning to alternative asset classes to take up the slack in creating client portfolios. But as we saw in our 2008 performance chart, without bonds, only gold delivered. Real estate (REITs), commodities, and emerging-market asset classes declined almost as much as stocks, providing little investor protection.

Fortunately, there is another class of “alternatives” that can fill the void. Alternative strategies also tend to be uncorrelated to stocks. These actively managed methodologies can take the place of bonds in diversified portfolios.

And research, such as Guggenheim’s white paper “The Diversification Dilemma: Tactical Management and Today’s Evolving Markets,” shows that while traditional alternative asset classes often fail to diversify when you need the diversification most—like in 2008—portfolios made up of alternative strategies can actually increase their diversifying power in times of crisis.

Strategic diversification vs. asset-class diversification—A better way?

I have extolled the virtues of strategic diversification since 1998. But what is strategic diversification? It’s simply a portfolio diversified using dynamically risk-managed strategies rather than just asset classes.

You build these strategy portfolios in the same way that you create diversified asset-class portfolios, but using portfolios of multiple strategies instead. And the strategies are chosen in the same way as the asset classes are chosen. You want strategies that are uncorrelated, that have their inevitable drawdowns at different times from each other, and that have daily and weekly returns that zig when the others zag. Fortunately, when compared with asset classes, there are many more strategies to choose from that are uncorrelated with stocks.

We do not want strategies that all go up in value together. We want strategies that respond to different economic stimuli and appreciate and depreciate at different times from each other.

While our firm has many different approaches for building a portfolio that is diversified with dynamically risk-managed strategies, here is a broad overview of one such approach:

We would use a core strategy for at least 60% of the portfolio. Preferably this would be an actively managed, suitability-based portfolio. It would likely be one that would rotate to a collection of the strongest-ranked asset classes—holding the leaders and avoiding the laggards. This is designed to deliver two solutions. First, it seeks to keep the portfolio in step with the gains attainable from the stock market. Second, it allows us to make sure the portfolio is suitable for the level of risk at which our clients are comfortable. The balance of the portfolio would be used to add strategies uncorrelated to the stock market. Normally, these are actively managed bond, gold, and contrarian strategies that often do not perform as strongly during bull markets but mitigate losses in bear and sideways markets.

***

Yes, diversified portfolios are like mixed-breed mutts—they give you the benefits of their many components without the higher risk of the negatives of each individual breed. At the same time, I look at a portfolio of strategies as opposed to asset classes as the best of the litter.

When researching this article, I learned that there are now dog shows for mutts. That means that our loveable mutts can finally get their recognition. Who knows, one of our two rescue dogs may become “Best in Show” yet. Molly and Abby, there’s still hope!

Jerry C. Wagner, founder and president of Flexible Plan Investments, Ltd. (FPI), is a leader in the active investment management industry. Since 1981, FPI has focused on preserving and growing capital through a robust active investment approach combined with risk management. FPI is a turnkey asset management program (TAMP), which means advisors can access and combine many risk-managed strategies within a single account. FPI's fee-based separately managed accounts can provide diversified portfolios of actively managed strategies within equity, debt, and alternative asset classes on an array of different platforms. flexibleplan.com

Jerry C. Wagner, founder and president of Flexible Plan Investments, Ltd. (FPI), is a leader in the active investment management industry. Since 1981, FPI has focused on preserving and growing capital through a robust active investment approach combined with risk management. FPI is a turnkey asset management program (TAMP), which means advisors can access and combine many risk-managed strategies within a single account. FPI's fee-based separately managed accounts can provide diversified portfolios of actively managed strategies within equity, debt, and alternative asset classes on an array of different platforms. flexibleplan.com