Mitigating bond risk in an uncertain interest-rate environment

Mitigating bond risk in an uncertain interest-rate environment

Holistic active investment management, as well as specific tactical bond strategies, can help advisors grow and protect their clients’ portfolios in a changing interest-rate environment.

There is another outcome, one that isn’t discussed. What happens if rates continue to slowly move higher or something happens that prevents central banks from increasing rates? What happens if rates don’t spike higher the way experts have predicted for years?

Impact of the Great Recession

Since the end of the Great Recession, “talking heads” and well-respected investment professionals alike have sold the story of rising rates. The United States has engaged in several rounds of quantitative easing (QE) where the Federal Reserve engaged in open market activities, buying various maturities of U.S. Treasurys. The effect was demand for government bonds, which drove prices up and subsequently drove yields to all-time lows. Other countries around the world also engaged in their own interest-rate cuts and various forms of QE.

Ever since rates hit all-time lows, the conversation has been about rising rates. The assumption is that when rates rise, it will be fast, significant, and cause notable losses for holders of individual bonds, bond funds, and interest-rate-sensitive investments. In 2010, The New York Times published an article titled “Interest Rates Have Nowhere to Go but Up.” At the time, the article reported the Mortgage Bankers Association expected the 30-year mortgage rate to rise to 6% by the end of the year.

The article continued along these lines, reporting that Washington expected rates to increase. “The Office of Management and Budget expects the rate on the benchmark 10-year United States Treasury note to remain close to 3.9 percent for the rest of the year [2010], but then rise to 4.5 percent in 2011 and 5 percent in 2012.”

This never panned out the way the article or anyone else expected. Instead, rates continued to fall, with the 10-year Treasury average falling to 2.8% in 2011 and then falling again in 2012 to an average of 1.8%. This contrasts with calls of a bottom in 2010 and increases in following years. According to the Federal Reserve Economic Data (FRED) database published by the St. Louis Federal Reserve Bank, rates never rose for the 10-year Treasury above the 3.9% rate expressed in The New York Times article. Since interest rates and Federal Reserve monetary policy are so tightly linked, “Fed-watching” has become a cottage industry of its own.

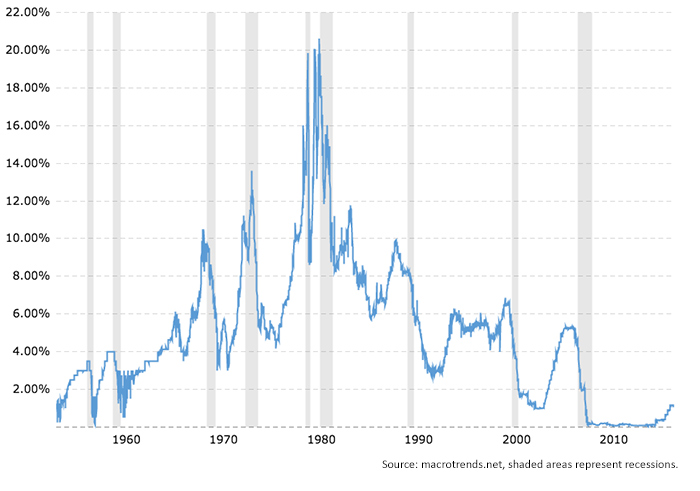

FIGURE 1: 10-YEAR TREASURY CONSTANT MATURITY RATE

The Fed’s dual mandate

The Federal Reserve Bank of the United States operates with a dual mandate. Its origin can be traced back to the 1970s with the foundation being laid after World War II when soldiers returned home looking for work.

The Fed’s mandates are to maximize employment and create price stability through consistent inflation via its monetary policy and open market operations. The Fed’s monetary policies control the interest rate and which banks engage in short-term loans, called the federal funds rate, and open market operations, which refers to the Fed’s interaction with dealers on a day-to-day basis.

Finally, the Fed also controls monetary policy through bank reserve requirements, which dictate how much capital a bank must keep on hand as opposed to lending out. The higher the reserve requirement, the less money a bank can lend—which creates demand for loans and drives interest rates up, while keeping reserves on hand reduces the supply of money circulating within the system.

With such extensive tools at its disposal, the Fed can and will have the dominant role in how and when “real” interest rates rise (nominal interest rate less the inflation rate). At each meeting, they analyze a litany of economic factors and decide whether to raise, lower, or keep rates the same in order to execute its mandate. If the Fed lowers rates, the effect is an increase in money supply and a reduction of borrowing costs, which it believes will inspire businesses to make investments in both human and physical capital. By doing this, the Fed is working toward its goal of maximum employment.

On the other hand, the Fed also has a mandate of maintaining price stability with a consistent long-run inflation target of 2%, a number that is set and reviewed by the Fed. With regard to its inflation target, the Fed has said, “Over time, a higher inflation rate would reduce the public’s ability to make accurate longer-term economic and financial decisions. A lower inflation rate would be associated with an elevated probability of falling into deflation, which means prices, and perhaps wages on average, are falling—a phenomenon associated with very weak economic conditions.”

Since the Great Recession, unemployment has come down steadily and inflation has remained relatively subdued, well within an acceptable range of its target. How quickly the discount rate can be raised without hampering economic activity and causing a sharp rise in unemployment is a dance the Fed will have to master going into the future.

In response to the Great Recession, the federal funds rate dropped from more than 5% in 2006 to a low of 0%–0.25% in December 2008. While the Fed was vigorously slashing interest rates, unemployment had soared, doubling from January 2008 to October 2009. Since then, unemployment has steadily declined to pre-recession levels; however, interest rates remained historically depressed.

FIGURE 2: FEDERAL FUNDS RATE—HISTORICAL CHART

Several concerns have contributed to the Fed’s reluctance to raise rates. In 2011, a statement issued by the Fed said, “The economic recovery is continuing, though at a rate that has been insufficient to bring about a significant improvement in labor market conditions.” Later in the statement, a cited concern was a slower-than-expected decline in the unemployment rate. This makes sense given that the world was coming out of the greatest financial collapse of the century and unemployment remained high relative to its target.

Six years later, the language has changed and so has the Fed’s position on raising rates. Now the Fed is focusing on managing inflation, concerning itself with maintaining price stability; however, the statement always wraps up with language similar to what is found in a June 2017 policy statement: “The federal funds rate is likely to remain, for some time, below levels that are expected to prevail in the longer run. However, the actual path of the federal funds rate will depend on the economic outlook as informed by incoming data.”

What this means is that the Fed is currently committed to raising rates at a pace it feels will not create a significant market or economic disruption. Therefore, the federal funds rate is likely to be lower than where the Federal Reserve would like it to be from a theoretical or macroeconomic perspective. The caveat to this is that the actual path will be determined by future economic data. The door is still open to either stop raising rates or lower them if they feel economic conditions begin to deteriorate.

What interest-rate outcomes seem most likely now?

The rising-rates dilemma exists only because the financial community is convinced interest rates must go up and that any increases will be sharp and fast, causing widespread pain for debt holders. As previously noted, financial industry experts have forecast increases in interest rates for nearly a decade, and, basically, none of these predictions have come to fruition. So what is more likely to happen? One of two outcomes seems most likely now: (1) rates will continue to rise but at a much slower pace than expected, or (2) a deterioration of the global economic outlook will lead to a severe slowdown in rate hikes or reverse rate increases altogether.

In an environment where interest rates rise slow and steady, investors will be able to diversify maturity-restricted fixed-income portfolios. Over the last decade, advisors moved client funds from diversified ladders and other portfolios with mixed durations to those consisting of primarily short-duration instruments with an expectation that rates have to move higher. If rates move higher more slowly than anticipated, investors will do well by diversifying bond maturities and “riding the yield curve.”

Riding the yield curve is a well-known fixed-income management style that takes advantage of time. As time passes, the bond’s maturity approaches, and an individual bond will move from maturing in a long time to a short time. Bond-fund managers will benefit as bonds come due because they will reinvest proceeds into assets that reflect the current interest-rate environment. With a slow rise in rates, there will be no portfolio impact, or it will be heavily muted by the normal move of individual bonds toward maturity. This style of investing may also be beneficial should the global economic situation experience a material and negative shift.

Actively managed strategies can mitigate risk in an uncertain interest-rate environment

Markets fluctuate over time, moving from bull markets to bear markets. They also experience recessions periodically. After a lengthy bull market, it’s reasonable to expect that at some point an equity bear market will present itself. In this situation, owning fixed-income investments is perceived as beneficial as investors flee risk assets and move toward “safety.”

Markets fluctuate over time, moving from bull markets to bear markets. They also experience recessions periodically. After a lengthy bull market, it’s reasonable to expect that at some point an equity bear market will present itself. In this situation, owning fixed-income investments is perceived as beneficial as investors flee risk assets and move toward “safety.”

When the global market begins to shake, the Federal Reserve may halt subsequent rate increases and could reduce rates to stir economic activity. In both cases, fixed-income investors will benefit as investors demand the relative safety of bond investments. After a lengthy bull market of any kind, it’s reasonable to consider how to protect a portfolio in the next bear market and also hedge the risk of a sharply rising rate environment.

Actively managed portfolios can offer competitive investment returns today while keeping an eye on future developments. With an actively managed bond portfolio, assets are positioned in a way that reflects the current environment through mathematical models and using a wide variety of investment instruments to capitalize on opportunities as they occur in real time. Fixed-income portfolios using this approach may consist of long maturity bonds or even longer-dated high-yield debt investments.

Robust actively managed portfolios focus on price and yield trends along with volatilities of assets at various maturities. Trends are used to identify and seize those opportunities that others are finding attractive (momentum) while the risk of a major turnaround is managed using volatility. As trending assets fall out of favor, it’s common to see a slowdown in price appreciation and a pickup in volatility.

As trends change, true active managers use the full array of tools available to generate positive returns for investors. Most mutual fund fixed-income managers are required by prospectus to maintain a certain level of investment at all times, are limited in the use of leverage, and do not allow short selling.

True active managers are adaptive and unafraid to use these tools advantageously to reduce portfolio volatility and increase return opportunity. For instance, should rates increase sharply, active managers can move into a heavy cash position or, if a sustainable downward trend exists, can use inverse ETFs and mutual funds to a portfolio’s benefit as rates rise and bond prices fall.

Regardless of whether a quantitative or qualitative approach is used, an intelligent approach focused on these types of elements can mitigate interest-rate risk for investors. If the market experiences the less-likely event of a sharp rise in rates, an actively managed portfolio will reposition into shorter-term assets—those that will be less affected by rate increases.

If the market continues as it has—a slow steady grind with minimal rises in rates—then portfolios will reflect this, owning a combination of longer-dated and higher-yielding bond instruments. In this case, an actively managed portfolio similar to one used for a rising rate environment can be adopted; however, investors also have the capacity to incorporate more passive techniques such as “riding the yield curve.” In either case, whether it’s a sharp and fast rise in rates or a slow and steady grind higher, investors’ total portfolios will benefit from incorporating an active fixed-income investment approach.

This becomes particularly important for aging baby boomers, who are seeking capital preservation as much as returns and have increased their allocations to fixed-income investments. According to a recent Investment News article:

“The past five years, investors have poured $634 billion into taxable bond funds and ETFs, according to the Investment Company Institute, the funds’ trade group. At the same time, investors have yanked $9.5 billion from domestic stock funds and ETFs.

“How has that worked out? For bond investors, not so well. … Bond prices fall when interest rates rise: The total return for the Bloomberg Barclays Aggregate Treasury index has been just 1.24% annually for the past five years, less than the 1.30% rise in inflation over the same period.”

There is little to be sure of in the future—whether rates move sharply higher, or slowly move higher over a long time period, or a global recession halts economic activity again and rates move back to a downward path. Using an adaptive active management style for fixed-income portfolios can provide advisors and their investor clients with enhanced risk mitigation regardless of how the future unfolds.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Proactive Advisor Magazine. These opinions are presented for educational purposes only.

William Hubbard, CFA, is a quantitative money-management analyst. He has spent his career focusing on how active management can generate results regardless of market direction. He earned his bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering, with a minor in economics, from Oakland University.

William Hubbard, CFA, is a quantitative money-management analyst. He has spent his career focusing on how active management can generate results regardless of market direction. He earned his bachelor’s degree in electrical engineering, with a minor in economics, from Oakland University.