Are we looking for investment answers in all the wrong places?

Are we looking for investment answers in all the wrong places?

One of the most seductive words in investing is “because.” If one understands the “because,” many investors believe, then the answer to “what happens next” is assumed to be within reach. Ideally, a logical pattern emerges that indicates future price direction, and the risk of investing can be managed.

A multi-billion-dollar industry is focused on supplying the “because” of financial markets’ behavior. Prices were up today because … Prices were down because … There are a host of reasons for every market action and for the direction of the next market move.

Well-known market technician Ralph Acampora maintained in early November that the stock market was in bad shape—worse than many Wall Street investors appreciate. “Honestly, I don’t see the low being put in yet and I think we’re going to go into a bear market,” he said.

Tom McClellan, another high-profile chart technician and publisher of the McClellan Market Report, told MarketWatch at roughly the same time that the recent action was more a function of seasonal volatility associated with October, and not a more significant upending of a 10-year bull market.

Two highly respected market technicians, two opposing viewpoints. Is one right and the other wrong, or is a coin toss just as reliable a forecast?

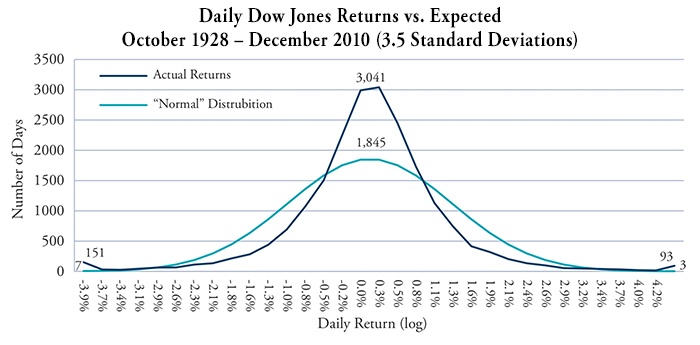

The principles of modern finance are very much a result of the human need to understand the “because” of market behavior and to define future behavior through a series of “rules.” The efficient market hypothesis, modern portfolio theory, the efficient frontier, the capital asset pricing model, and a multitude of market theorems seek to impose order on financial markets. Unfortunately, these theories fail when they are needed most: when market trend changes direction. Among their greatest fallacies is trying to fit financial market behavior into a statistical bell curve.

Markets are ‘wilder and milder’ than expected

On Oct. 19, 1987, the Dow Jones Industrial Index fell 29.2%. Based on a “normal” distribution—the logic that underlies beta and the calculation of risk—the probability of that happening was less than one in 1050 (10 to the 50th power). Oct. 19 was by no means an isolated anomaly. Market moves are much more volatile and extreme than predicted by a normal distribution. The use of algorithms and computerized trading promise to accentuate and compress volatility even more going forward.

FIGURE 1: DISTRIBUTION OF ACTUAL RETURNS DEVIATES FROM ‘EXPECTED’ DISTRIBUTION

Source: Bob Maynard, chief investment officer at the Public Retirement System of Idaho,

“Managing Risk in a Complex World.” October 2014.

According to probability statistics, a loss greater than 3.9% should have occurred seven times during the 82 years from 1928 to 2010. In reality, there were more than 151 single-day declines in excess of 3.9%. The probability of the Oct. 19, 1987, Dow decline of 29.2% in one day was, statistically speaking, virtually impossible. The probability that the Dow would record single-day drops of 3.5%, 4.4%, and 6.8% in one month was 1 in 20 million. Bob Maynard, chief investment officer for the Public Retirement System of Idaho put his view of market behavior succinctly and memorably in an article in 2014: Markets are “wilder and milder” than expected.

Does chaos theory present a more realistic model for the markets?

The one theory that has proven to create the most accurate simulation of market behavior so far is chaos theory—and that theory changes the entire investment game.

Chaos theory says that in the real world, causes are usually obscure. Critical information is often unknown or unknowable, making it impossible to predict the fate of a complex system.

Chaotic systems are predictable for a while and then “appear” to become random. In “The Black Swan,” Nassim Taleb uses the term regime change to describe transitions in chaotic systems. “Black swan” events occur, he says, because rules developed from the observation of events never contain the full range of possibilities. Within that apparent randomness, however, are underlying patterns, constant feedback loops, repetition, self-similarity, fractals, self-organization, and dependence on initial conditions. Chaos is not simply disorder, but the transition between one condition and the next.

Price changes are not independent of each other but rather have a “memory,” according to mathematician Benoit H. Mandelbrot (1924–2010). Contrary to the disclaimer that past performance is not indicative of future returns, chaos theory says today does, in fact, influence tomorrow.

An excellent book for rethinking the financial markets in the framework of chaos theory is “The (mis)Behavior of Markets: A Fractal View of Risk, Ruin, and Reward,” published in 2004 by Mandelbrot and his co-author Richard Hudson. Mandelbrot makes it impossible to listen to a financial news program or read the market analysis of the day without thinking, “What a humbug.”

Reframing financial markets in the context of complexity gives greater insight into why investment theories and strategies can appear to work, only to fall into disarray when market conditions change. “The (mis)Behavior of Markets” shakes one out of habitual ways of viewing the markets to understand why active investment management is so essential. What has been true is not guaranteed to remain so. Is reversion to the mean a lasting phenomenon or one subject to change? Is there a way to measure value, or is it all relative to the current market? If changes too small to be commented on at the time are creating large differences in a later period, does the cause cited in the evening news have any validity? If directional change results not from factors that we are aware of but those not considered, does anything matter other than the present?

What matters in chaos theory is not the “because” but rather the present action of the market. Given that all of the initial conditions of a complex system are not fully knowable, it is impossible to predict the fate of a complex system.

It is, however, possible on a short-term basis to detect trends and patterns in the market and, most importantly, to accept the possibility and reality of a change in direction.

Unlike most books on the financial markets, “The (mis)Behavior of Markets” does not provide any investment answers or secrets of success, but rather focuses the reader on the realities of the market from a mathematician’s view, placing no value in averages or theories.

‘10 Heresies of Finance’

Toward the end, Mandelbrot sets forth “10 Heresies of Finance.” Below, his rules are listed and brief statements are derived from his explanations to give a flavor of his arguments. A full reading of the “10 Heresies” is warranted for a better understanding.

1. “Markets are turbulent.”

A turbulent process is one that proceeds in bursts and pauses and whose parts scale fractally, all interrelated from the start to the end of the journey.

A fractal is a pattern or shape whose parts echo the whole, as seen in Figure 2.

FIGURE 2: FRACTAL IMAGE

2. “Markets are very, very risky—more risky than the standard theories imagine.”

Turbulence is hard to predict, harder to protect against, hardest of all to engineer and profit from. Conventional finance ignores this.

3. “Market ‘timing’ matters greatly. Big gains and losses concentrate into small packages of time.”

What matters is the particular, not the average. Some of the most successful investors are those who did, in fact, get the timing right.

4. “Prices often leap, not glide. That adds to the risk.”

The mathematics of Louis Bachelier, Harry Markowitz, William Sharpe, Fisher Black, and Myron Scholes all assume continuous change from one price to the next. Given that equity prices do not change incrementally from one price to the next, but rather leap over gaps to the next price, their formulae simply do not work, especially in today’s fast-paced markets.

5. “In markets, time is flexible.”

The genius of fractal analysis is that the same risk factors, the same formulae, apply to a day as to a year, an hour as to a month. Only the magnitude differs.

6. “Markets in all places and ages work alike.”

One of the surprising conclusions of fractal market analysis is the similarity of certain variables from one type of market to another.

7. “Markets are inherently uncertain, and bubbles are inevitable.”

This one you should really read for yourself. It is a fascinating mind-bender, as it explores the consequences for financial markets of “scaling.”

8. “Markets are deceptive.”

People want to see patterns in the world. It is how we evolved. It is a bold investor, however, who would try to forecast a specific price level based solely on a pattern in the charts.

9. “Forecasting prices may be perilous, but you can estimate the odds of future volatility.”

It may well be that you cannot forecast prices, but evaluating risk is another matter entirely.

10. “In financial markets, the idea of ‘value’ has limited value.”

Value is a slippery concept and one whose usefulness is vastly overrated. The prime mover in a financial market is not value or price, but price differences; not averaging, but arbitraging.

***

In the end, there is only one number that really matters: the price provided by the market—not theories, hopes, or speculation. And that perhaps informs some of the most important tools of active investment management.

“All you really need to know for the moment is that the universe is a lot more complicated than you might think, even if you start from a position of thinking it’s pretty damn complicated in the first place.”

— Douglas Adams, author and satirist

“Knowing the limits of our ability to predict is much more important than the predictions themselves. …”

— Tom Konrad, author and financial analyst

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Proactive Advisor Magazine. These opinions are presented for educational purposes only.

Linda Ferentchak is the president of Financial Communications Associates. Ms. Ferentchak has worked in financial industry communications since 1979 and has an extensive background in investment and money-management philosophies and strategies. She is a member of the Business Marketing Association and holds the APR accreditation from the Public Relations Society of America. Her work has received numerous awards, including the American Marketing Association’s Gold Peak award. activemanagersresource.com

Linda Ferentchak is the president of Financial Communications Associates. Ms. Ferentchak has worked in financial industry communications since 1979 and has an extensive background in investment and money-management philosophies and strategies. She is a member of the Business Marketing Association and holds the APR accreditation from the Public Relations Society of America. Her work has received numerous awards, including the American Marketing Association’s Gold Peak award. activemanagersresource.com

Recent Posts: