Why proactive money management makes sense for clients

Why proactive money management makes sense for clients

When it comes to managing money, focus first on risk management, defending a portfolio from losses. This doesn’t mean being overly conservative—but a great offense without an equally great defense achieves little for clients in the long run.

We all have moments in our lives that become engrained in our minds forever. Whether good or bad, these memories often make a huge impact on your attitude and outlook on life.

I made one of those memories just this past December. I was trying to convince another professional in our industry (a relatively new advisor with our firm) why active, tactical portfolio management was superior to the archaic, passive “buy-and-hold” model.

It wasn’t the first time we’d talked about this. Unfortunately, each of these discussions seemed to turn into an endless—not to mention hopeless—argument, similar to a long, wasteful debate about politics.

This conversation was prompted by a client leaving our firm after only 15 months. He had hired us in the summer of 2015, just before what some call “Gray Monday,” the extreme global sell-off of Aug. 24, 2015, that started with fears over China’s economic growth. After giving an active, tactical portfolio-management strategy just over a year to “work,” this client decided he couldn’t take it anymore and fired us shortly after the November 2016 election, which also happened to be when we re-exposed portfolios to the stock market.

This other professional, who I’ll call “Joe,” argued that, if we had held on to a portfolio of investments and left it alone, the client would’ve been better off, and we likely would not have lost them. This Monday morning quarterbacking was not very useful.

He went on to say that, according to charts he’d looked at, even if you went back to 1995, investors would be better off if they simply held the S&P 500 the entire time without selling.

The biggest roadblock in this discussion was Joe’s lack of experience. Ironically, he started his career in the summer of 2009, just after the biggest stock market crash in decades. Joe had never experienced the market downturns many professional money managers and investors had gone through—not once, but twice in the last 20-plus years. As a result, his psychology was skewed to only look at one side of the story—price movement over time with hindsight at his advantage.

I tried to explain that there is a lot more to successful investing throughout an average investor’s lifetime and retirement, and that even a simple moving-average crossover system would be an elementary, yet sufficient, method of risk management.

I pulled up some charts to show him, one of which is shown in Figure 1. It represents a 100-over-150-day exponential-moving-average (EMA) crossover system. The way this system works is simple. When the 100 EMA crosses above the 150 EMA, you buy the index (think SPX). Conversely, when the 100 EMA crosses back below the 150 EMA, you sell the position and head to cash (for a more conservative position). Or, you could even buy the inverse of the S&P 500—$SH is a good choice in my opinion.

The time an investor following this system would have spent invested in the S&P 500 is shaded, and the time the investor would have spent on the sidelines in a money-market fund is unshaded.

FIGURE 1: S&P 500 20-YEAR CHART WITH 100/150 EMA CROSSOVER

I also showed him two separate time frames: one that included the latter part of the longest bull market in U.S. history (Figure 1), and one that began just before the dot-com crash beginning in 2000.

I wanted to show Joe that it didn’t matter whether we started the clock during a bull market or at the very beginning of a bear market. The bottom line is that you can’t allow clients who want to retire someday to just passively sit in the market “all in, all of the time,” unless they’re ridiculously rich and/or don’t spend any money.

Why? If clients simply buy, diversify, and hold through bear markets, they will experience the effects of several negative outcomes:

1. Steep losses can take three to more than eight years to recapture.

2. We’ve all seen the DALBAR studies that repeatedly demonstrate that self-directed investors rarely stay fully invested through an entire bear market and, frankly, poorly time when to get back in the market.

3. Individuals or couples taking income from their portfolios will find their portfolios radically decimated from the standpoint of future income, inflation protection, and, of course, the long climb up the hill toward breakeven.

Still, Joe wasn’t convinced. He began quoting mutual fund propaganda: “But if the market crashes, you still own the same number of shares you did before, so you’ve only lost money if you sell them.”

My response was, “You haven’t made anything unless you sell them.”

Joe wasn’t seeing the big picture. He was missing an enormously critical piece of the equation.

Let’s say you’re on a boat with some friends, considering whether any of you can hold your breath long enough to touch the bottom of the lake. Using some loose math that includes the depth of the water, the average time a person can hold his or her breath, fitness level, and swimming expertise, some might think they could pull off the feat. However, if you do the math and determine you can touch bottom, you had better also do the math to ensure you can make it back up to the surface!

So what was the missing piece in Joe’s argument? Systematic withdrawals.

The conversation finally started to go my way when I said to him, “If you want to put a sign on our door that says we’re the firm to come to if you never want to spend your money, then, yes, leaving your money in the S&P 500 and never touching it works fine. Come to think of it, you could put your money in almost anything if you’re never going to spend it. But that’s not what our clients want. Most investors want to save their money so that one day they can have the choice to quit working and travel, take up hobbies, and spend time with their children and grandchildren. This almost always requires a supplemental income stream, which would more than likely come from the portfolio we manage for them.”

For those who’ve been in this business for as long as I have (16 years) or longer, you might know what it feels like to sit face-to-face with a client who’s lost a lot of money on your watch due to buy-and-hold portfolio management during and after a market crash. Often, these clients are forced to either delay retirement or, if they are already retired, get back into the workforce.

I started in this industry just two weeks before the World Trade Center terrorist attacks on Sept. 11, 2001. I was hired by a national brokerage firm. Most firms at that time—including the one I worked for—abided by the buy-and-hold philosophy. Unfortunately, I learned what it felt like to lose clients’ money at a young age. Thankfully, I encountered this hard lesson early in my career.

Even when the market starts to come back and your clients are getting near breakeven, do you think they care about how their portfolio did during those comeback years? Nope. They’re still in the red, and that is all that matters.

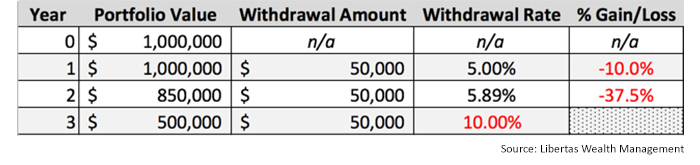

Still think passive investing makes sense for your clients? Here’s how the math works. Let’s say a relatively wealthy investor retires with $1,000,000 in total assets, withdrawing $50,000 a year to supplement their Social Security income, just before a market crash.

TABLE 1: EFFECTS OF PORTFOLIO DRAWDOWN ON WITHDRAWAL RATE

As you can clearly see in Table 1, the $50,000 withdrawals each year are, at first, equivalent to 5% of the initial portfolio value. However, when faced with a significant market crash, which takes roughly 18–24 months to run its course, the withdrawals combined with losses in the market translate into a much higher withdrawal rate.

In fact, using the simple example above, this investor’s new break-even point is 10%, net of taxes, fees, and inflation. Do you think your client’s $500,000 in remaining account value would last the rest of his or her life at this point?

The way I see it, imprudent, improper, and/or total lack of proactive risk management in this client’s portfolio could force the client to face one or more of the following regrettable scenarios:

1. Having to gain employment to fill the gap created by market losses.

2. Being forced to reduce yearly withdrawals, thus diminishing the client’s retirement lifestyle.

3. Running out of money at some point during retirement before passing away, leaving the client financially ruined and demolishing any chance of a family legacy.

The average bull market lasts roughly seven years, and we’ve now entered year nine of the current bull market run. In addition, this is the second-longest bull market in history (the longest being the huge run from 1987 to 2000).

If we know that the market crashes every seven years, on average, and we also know that the average crash results in a loss of roughly 42%, do you think we’re closer to the top or the bottom at this juncture?

As a proactive, trend-following portfolio manager, I don’t proclaim to know the answer to this question. To clarify, I am not a trend predictor. There is no such thing as a consistently successful trend predictor.

Rather, I’m a trend-follower. The beauty of active portfolio management is that you don’t have to know the future to produce successful results in your clients’ portfolios. You do have to pay attention, follow rules, and stick to your strategy when the trends start to break down. With today’s advances in technology, successful active strategies can be effectively implemented through mechanical, quantitative approaches that are computer-driven.

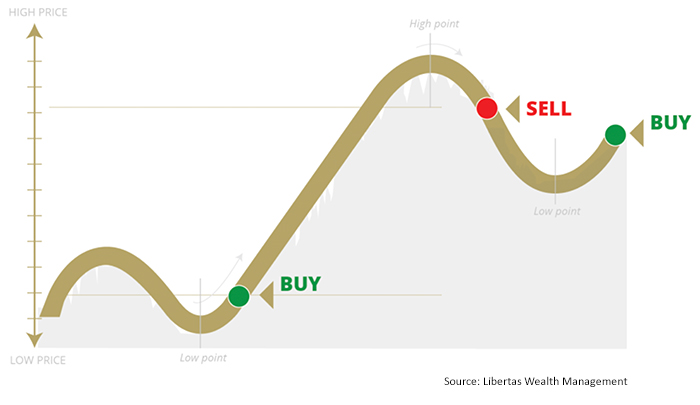

We believe maintaining a non-emotional, rules-based, technical approach to money management can outperform “buy-and-hope” portfolios over the course of a full market cycle. One of our objectives is to buy when markets are recovering from a bear market or advancing in a strong bull market. We attempt to start selling after the peaks have passed, trying to miss as much of the downside as possible. Think “maximum up-capture; minimum down-capture.” I like to tell clients, “I manage risk more than I manage investments.”

FIGURE 2: CONCEPTUAL MODEL FOR BUY/SELL POINTS

The great thing about tactical money management is that you’re likely going to do relatively well when the market is trending up or down. The penalty for such a strategy is the occasional, yet inevitable whipsaw. This means that flat, trendless markets—such as the one we experienced from 2015 to 2016—are going to be painful, underperforming years for the proactive portfolio manager.

When those inevitable whipsaws and sideways markets make your job difficult, remember, communication is the key to successful relationships with your clients. When a sideways market resolves to the upside and they become frustrated with you, remind them of the reasons they’re investing their money with you.

As the great Bear Bryant once said, “Offense sells tickets, but defense wins championships.” While this analogy works best with football fans, I think the message is clear. Making money in a bull market isn’t really all that tough. It’s defending your clients’ portfolios against catastrophe that is the hard part. It’s why putting defense first by tactically managing money with active portfolio management is, in my opinion, far superior to “buy and hope.”

I often tell clients, “I’d rather be out of the market when it’s going up, than in the market when it’s going down.” And I demonstrate with the facts why this will enhance the probability of their being able to continue their lifestyle tomorrow and long into the future.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Proactive Advisor Magazine. These opinions are presented for educational purposes only.

Adam Koos, CFP, CMT, CFTe, CEPA, is the president and portfolio manager at Libertas Wealth Management Group Inc., a NAPFA-affiliated, fiduciary registered investment advisor firm in Columbus, Ohio. Since founding the firm in 2001, he has earned local and national recognition, including being named one of the Top 100 Most Influential Financial Advisors in the U.S. by Investopedia and receiving the Torch Award for Ethics and Trust from the Better Business Bureau. Mr. Koos holds B.S. degrees in finance and behavioral psychology from The Ohio State University. www.libertaswealth.com

Adam Koos, CFP, CMT, CFTe, CEPA, is the president and portfolio manager at Libertas Wealth Management Group Inc., a NAPFA-affiliated, fiduciary registered investment advisor firm in Columbus, Ohio. Since founding the firm in 2001, he has earned local and national recognition, including being named one of the Top 100 Most Influential Financial Advisors in the U.S. by Investopedia and receiving the Torch Award for Ethics and Trust from the Better Business Bureau. Mr. Koos holds B.S. degrees in finance and behavioral psychology from The Ohio State University. www.libertaswealth.com