Keeping portfolio risk under control

Keeping portfolio risk under control

Understanding the tools to better manage portfolio risk throughout different market, volatility, and economic regimes.

One major gripe of mine is that some portfolio strategists who consider themselves to be risk managers are effectively just risk monitors. Rather than being proactive and trying to avoid risk, they spend their time analyzing and explaining why the risk occurred. Unfortunately, once an extremely adverse drawdown hits your portfolio strategy and performance history, it will shadow you for a very long time.

Portfolio risk management is simultaneously both a bottom-up and a top-down process. At the bottom, it is the control of individual trade or position risk; at the top, it is the control of portfolio volatility and the ability to define (and manage) risk expectations. In between, it requires continual balancing of risks so that no one set of assets dominates the performance.

It’s always easy to recognize risk when volatility is high, but it’s more important to see the potential risk when it’s not staring you in the face. For example, a long run of profits with low volatility can make investors complacent. Isn’t that what happened to Long-Term Capital Management before they imploded in 1998?

It’s always easy to recognize risk when volatility is high, but it’s more important to see the potential risk when it’s not staring you in the face. For example, a long run of profits with low volatility can make investors complacent. Isn’t that what happened to Long-Term Capital Management before they imploded in 1998?

In my experience, there is no such thing as low risk, unless you have correspondingly low returns. A prolonged period of profits with little risk is always a nice respite from uncertainty, but you shouldn’t take it as the “new normal.” Risk is always there, hiding in the wings.

Investors or managers using algorithmic strategies, or tactical decision-making, will find that there are two dominant risk patterns:

1. Trend followers will have many small losses and a lesser number of large profits. That comes from cutting losses short and letting profits run, an approach called conservation of capital.

2. Mean-reversion traders and arbitrageurs do the opposite. They exploit price noise (a jump up or down destined to go nowhere) and unlikely divergences between similar markets. Their profile is a lot of smaller profits and a few large losses.

You can have some variation in between these two extremes, but it is extremely difficult to have many small profits and a few small losses, or not so many small losses and much larger profits. It’s best if you don’t waste time looking for a risk profile that doesn’t exist. “Letting the good times roll” is not a sound plan. Instead, you need to concentrate on managing risk.

It is my belief, and that of many active managers, that optimal portfolio allocation (picking something on the efficient frontier) is only something that works in theory. The best portfolio yesterday is the one that was on the right side of every correct earnings report, held the energy sector (XLE) when crude ran to $150 (but not when it dropped back to $30), and had a strong allocation to the financial sector (XLF) before the 2008 crisis (but not during the crisis). An optimized portfolio in many ways is essentially an exercise in chasing profitable positions of the past. It takes positions in markets that were good, without any idea of what the future will bring or having proper risk management in place.

- For individual assets and trades, focus on balancing risk, not balancing expected returns.

- Simple tools for measuring risk are often better than complex ones.

- Equal position weighting (that is, equal investments in each asset) maximizes diversification and adds to long-term stability.

- Volatility stabilization, where you reduce risk when it gets too high to maintain more constant risk, will actually increase returns and reduce risk.

It’s all about the money, not the investment philosophy and not the assets. When a crisis happens, investors (and professionals) go to cash. They sell anything that they are long and buy back anything they are short. They often liquidate profitable positions to cover losses in other trades. The net effect is that everything reverses—stocks, bonds, gold, art, you name it.

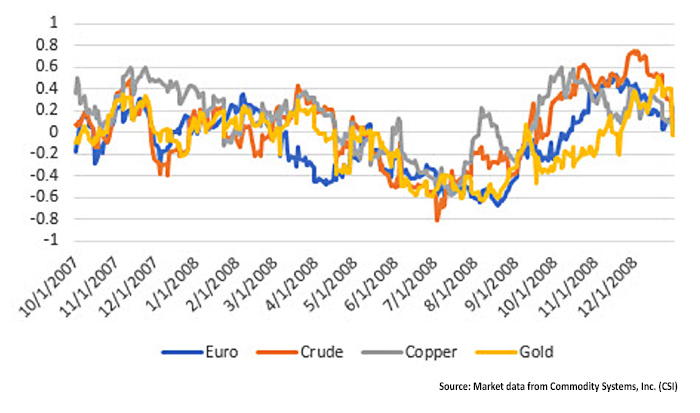

The statisticians say the “correlations go to 1,” but what they mean is that the correlations (the price relationship of other markets to the S&P) converge. Instead of providing diversification, they move together. In Figure 1 you see four very different markets: the euro currency, crude oil, copper, and gold. These markets normally vary in their relationship to the S&P (and offer diversification), but all converged to -0.6 in the middle of 2008, a strong negative correlation to the S&P. When the S&P went down, all those markets went up. Not much diversification there.

(IN NEGATIVE CORRELATION TO THE S&P 500)

While diversification is good, overdiversification is a waste of resources and opportunity. As you add more assets and even strategies, you bring in marginal performers. The first three or four strategies are the best, and any more than that, in my opinion, just dilutes performance without adding much in the way of returns.

Beta is a measure of the volatility of a single stock, or a portfolio, compared to a benchmark index, such as the S&P 500. If beta is 1.2, it means that the volatility is 20% higher. That will result in 20% more profits and 20% larger losses. Conservative investors will choose a portfolio with a beta less than 1.0, although a historic beta does not mean that a surprise announcement (such as earnings) won’t result in a move more volatile than expected.

Alpha is a measure of overperformance. It can be more return than the index with the same risk, or the same return with less risk. It says, “I’m doing better than the market.” It is easier to measure as a ratio of return to risk, as in the information ratio.

The standard deviation is the basic tool for measurement and is part of most risk evaluation. It gives you a probability rather than an absolute value. The likelihood of a gain or loss in the future is uncertain in both when it will occur and by how much, but standard deviation helps create useful parameters. Saying, “I don’t expect a loss greater than $1,000” is too specific to be realistic. If you say “there’s a 20% chance of losing more than 5% of my investment,” you are now dealing with probabilities that use the standard deviation.

Time to recovery is different in that it doesn’t care how big the loss was, only how fast the stock or portfolio recovered and made new highs. I like this measure, even though there are no guarantees. Given a choice of two portfolios, the one that was underwater for three months is much more attractive to me than the one that went sideways for two years.

The Sharpe ratio (and information ratio) is the most popular way of comparing the performance of two portfolios. It is the annualized return (AROR) minus the risk-free returns (for example, the yield on a one-year T-bill) divided by the annualized volatility. The information ratio ignores the risk-free return, which I prefer.

Morningstar’s upside/downside capture ratio treats monthly gains and losses separately, and then takes the ratio of the two. Over the period of the ratio (say one, three, or five years), if the fund had a positive month, it divides that return by the return of the benchmark, say SPY, during that same month to get the upside ratio. When it has a losing month, that return is divided by the return of SPY to get the downside ratio. The average upside ratios are divided by the downside ratios for the calculation period and multiplied by 100. Anything over 100 has beaten the SPY, indicating a better reward-to-risk ratio than the index.

Measuring only downside risk (semi-variance) is an alternative because it addresses only losses. Some investors believe that large upside moves should not affect the risk of a position or a portfolio. I think that’s nonsense. Volatility to the upside can just as easily become volatility to the downside, so ignoring half the data will lead you to underestimate the risks.

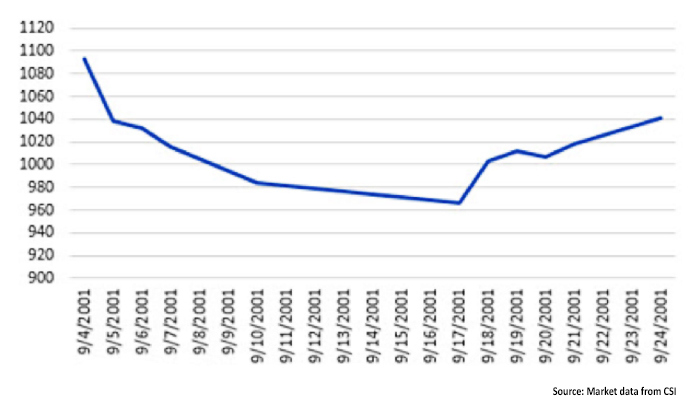

Monthly data is never as accurate as daily data. If the market had a tremendous drop during the month but a recovery before the end of the month, you would not see the real risk. If you think the risk is less, based on monthly data, you might be more aggressive in your investment. As an example, look at the S&P 500 Index (SPX) in September 2001. At its lows on Sept. 21, it was down 11.6%, but on Sept. 28, it was only down 4.7%. The only time monthly data would show the largest loss would be if that loss occurred on the last day of the month. That’s not a likely scenario.

Using maximum drawdown, either in absolute dollars or as a percentage, is the least accurate measure. It relies on a single number, or a single event, to define the risk. As time moves on, drawdowns can get larger and/or more frequent. As prices get higher, absolute losses will be bigger. Maximum drawdown is a helpful part of the risk big picture, but just one of many measures.

All of these indicators are dependent on price history—the time period that you use to find the indicator values. If you use only the last month, they won’t be very accurate. But how far back should you go to get a reasonable answer?

I don’t think the answer can be found using a formula. You need to have enough history to capture bull markets, bear markets, low and high volatility periods, and a few nasty price shocks. That will change over time. For now, going back to 1998 would cover it all. If you want a shorter period, start in 2007 to be sure you include the financial crisis.

There is only one measure that truly tries to anticipate future risk, and that’s value-at-risk (VaR). Value-at-risk takes your current portfolio assets and position sizes and looks to see what the daily profits or losses would have been if you had held these positions for the past six months, or year, or some other designated period. You get all of the daily results, and then sort them with the best returns on top and the worst on the bottom.

While VaR is used by most major institutions to control leverage in their investment portfolios, the significance and sensitivity of the analysis are entirely dependent on the data period used, just as with all of the other measurements. It does offer a different view because it shows the risk of the specific assets in your portfolio, rather than basing the measure on the aggregate portfolio returns.

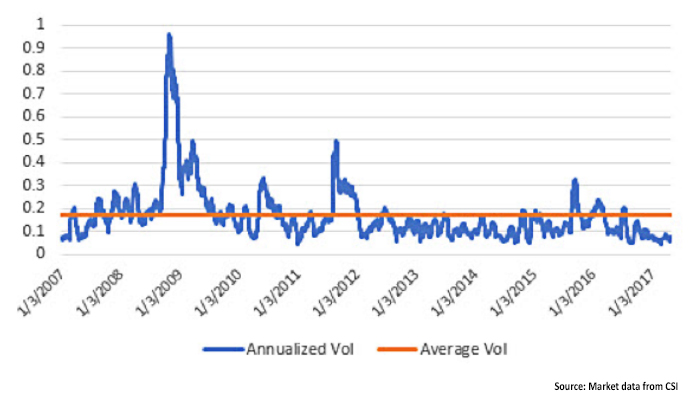

Another form of volatility management also offers a productive avenue for controlling risk, especially for active strategies that use leverage. The concept of “volatility stabilization” can help produce better returns at lower risk. In simple terms, this involves the reduction of leverage when volatility rises above its historical average (around 17%) and increasing leverage during periods when volatility is below its historical average. During the past five years, when volatility has been well below historical norms, adding leverage to strategies has been a very profitable tactical strategic element in portfolio management. But, historically, having a disciplined, rules-based approach for decreasing or eliminating portfolio leverage is as important as a risk-management tool.

Perry Kaufman is a financial engineer specializing in algorithmic trading. He is best known for his book, “Trading Systems and Methods,” (fifth edition, Wiley, 2013) and recently published “A Guide to Creating a Successful Algorithmic Trading Strategy” (Wiley, 2016). Mr. Kaufman has a broad background in equities and commodities, global macro trading, and risk management. Find more information at his website: www.kaufmansignals.com

Perry Kaufman is a financial engineer specializing in algorithmic trading. He is best known for his book, “Trading Systems and Methods,” (fifth edition, Wiley, 2013) and recently published “A Guide to Creating a Successful Algorithmic Trading Strategy” (Wiley, 2016). Mr. Kaufman has a broad background in equities and commodities, global macro trading, and risk management. Find more information at his website: www.kaufmansignals.com