Granddaddy of all market indicators

Granddaddy of all market indicators

The 200-day moving average.

Active management at its most basic is the attempt to position a portfolio on the right side of the market’s moves to capture a fair share of gains while minimizing portfolio losses. While today’s active management systems typically use a blend of strategies, algorithms, and technical models to do so, among the earliest mathematical tools for determining market direction (and still in use today) are moving averages.

The 200-day moving average is typically considered to be the dividing line between a stock or a market that is technically healthy and one that is not.

One of the most prevalent applications of active management is trend following. A trend-following approach attempts to determine short-, mid-, or long-term market trends and capitalize on the trend by buying and selling accordingly. To determine a trend, one needs a means of filtering out the “noise” of the market and daily volatility. Moving averages are one of many ways to do so.

The granddaddy of the moving averages is the 200-day moving average, typically considered to be the dividing line between a stock or a market that is technically healthy and one that is not.

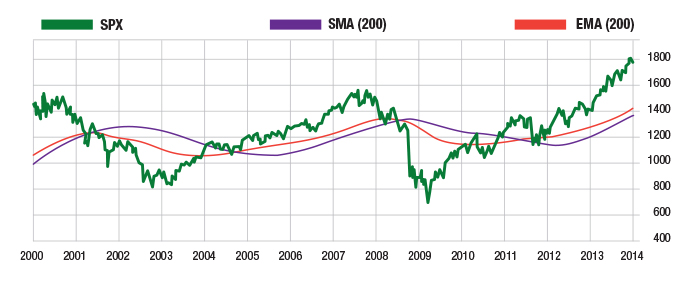

S&P 500 INDEX WITH SIMPLE AND EXPONENTIAL 200-DAY MOVING AVERAGES (2000-2013)

A simple moving average is calculated by adding the last 200 days’ closing prices and dividing by 200. Each day a new value is added and the oldest is dropped, moving it along the time line. Moving averages are easily calculated by hand, giving the tool long-term use well before the advent of today’s computing powers. The 200-day moving average also has the advantage of generating relatively few trades, which mattered quite a bit in the early days of its use, when trading costs were considerably higher than today.

As long as prices are above the 200-day moving average, the market is said to be in an uptrend. When values fall below the moving average, a downtrend is underway. When the gap between the moving average and the actual market value is wide, analysts believe a change in market direction is on the horizon.

One of the earliest, more basic active management systems was to hold a stock or index as long as its 200-day moving average was headed up and sell when the moving average turned down. Another way to view this is to hold a security as long as its 200-day moving average is below current market values and sell when the moving average moves above the security’s current price.

In 2012, Mark Hulbert published the results of a study backtesting the 200-day moving average to the late 1800s, when the Dow was created. His hypothetical portfolio was fully invested in the Dow whenever it was above its 200-day moving average and on the sidelines earning nothing when it wasn’t. “The long-term results were quite impressive. Compared to a 5.0% annualized return for buying and holding over this 115-year period, the 200-day moving average portfolio earned a 6.6% annualized return. Better yet, this outperformance was produced while simultaneously reducing risk by a big amount.”

What Hulbert found, however, was that the profitability of the strategy began to falter in the 1990s. “From the beginning of 1990 through Monday’s (6/10/12) close, for example, this hypothetical moving-average portfolio made just 4.0% annualized, compared to 6.8% annualized for buying and holding.”

One theory for the fall off in the effectiveness of the 200-day moving average is increased volatility and the speed with which the market now reacts to news. As a result, exponential 200-day moving averages have gained popularity. An exponential moving average applies more weight to recent prices, reducing the lag time between the market’s movement and the average.

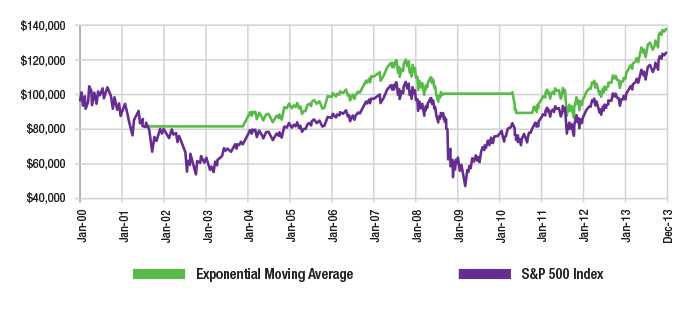

VALUE OF INVESTED DOLLARS BASED ON 200-DAY MA SIGNALS (2000-2013)

Because a moving average is created from past data, it always lags the actual market. The turnaround in market direction always happens before the moving average signals confirmation. In the previous graphic, the exponential moving average signals the change in market direction more quickly, but it also tends to encounter more whipsaws, as in 2010.

The question is, would this basic system have worked to the investor’s advantage? Because real investors don’t have the 100-plus year time frame Hulbert used in his study, the chart above looks at just the period from 2000. A $100,000 portfolio was invested in the S&P 500 Index when the moving average was below the actual market value and moved to the sidelines, earning nothing, when the indicator was above the index value.

Remember, this is a hypothetical example. The 200-moving-day average system works best during times of sharp price decline (two of which are included in the chart), but it is not that effective during times when prices zigzag on the way up.

While moving-average-based trading systems still have their fans and are used in risk-management approaches, active investment management models have become considerably more sophisticated over the last 20 years. Increases in the availability of data, greater computing power, new investment vehicles, and expanding market knowledge have led to enhanced investing approaches that strive to optimize returns and control risk through active management.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Proactive Advisor Magazine. These opinions are presented for educational purposes only.

Linda Ferentchak is the president of Financial Communications Associates. Ms. Ferentchak has worked in financial industry communications since 1979 and has an extensive background in investment and money-management philosophies and strategies. She is a member of the Business Marketing Association and holds the APR accreditation from the Public Relations Society of America. Her work has received numerous awards, including the American Marketing Association’s Gold Peak award. activemanagersresource.com

Linda Ferentchak is the president of Financial Communications Associates. Ms. Ferentchak has worked in financial industry communications since 1979 and has an extensive background in investment and money-management philosophies and strategies. She is a member of the Business Marketing Association and holds the APR accreditation from the Public Relations Society of America. Her work has received numerous awards, including the American Marketing Association’s Gold Peak award. activemanagersresource.com