They’ve got it backward!

Should buy-and-hold investors be more active and active investors more patient?

The message was buried in the lyrics and could be heard only when the record was played backward. Then came the news that if you played the Beatles’ “I’m So Tired” in reverse, you could clearly hear the band sing “Paul is a dead man, miss him, miss him, miss him.” With that, the “Paul is dead” phenomenon was launched. It occupied the fan media for two months, until Paul reappeared in a November 1969 Life magazine interview entitled “Paul Is Still With Us.”

The process of playing a recording in reverse is called backmasking. Even the inventor of the phonograph, Thomas Edison, is reported to have tried the process, saying in 1878, “the song is still melodious in many cases, and some of the strains are sweet and novel, but altogether different from the song reproduced in the right way.” In the years between the Beatles incident and the present, backmasking has inspired fears of satanic messaging, subconscious influencing, and even legislation to ban the practice.

It’s no wonder that the phrase “getting it backward” has become synonymous with screwing up or getting it wrong. Try tightening a screw in the wrong direction or intercepting a pass and returning it to your own end zone—just a few more examples of getting it backward.

Buy and hold fails behavioral test of time

After decades of listening to the debate between active and buy-and-hold investors, and seeing both types in action, I think each side has “got it backward.”

Proponents of buy-and-hold investing believe that stocks advance relentlessly over the long run. For that reason, and because shares otherwise behave in a random manner, the best an investor can do (they believe) is buy good stocks or mutual funds and hold on to them through thick and thin.

But I think history demonstrates that they’ve got it backward. Without even going back to the days of the Great Depression, one can readily see that the stock market periodically retraces its steps and then takes years to recover.

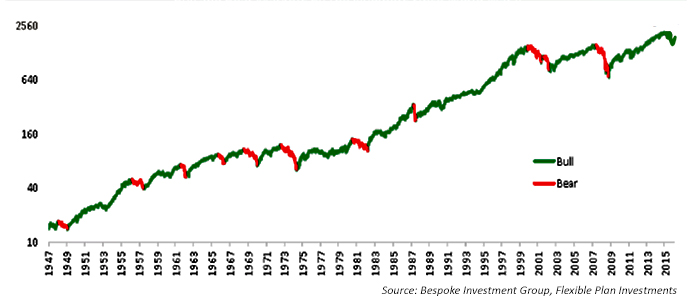

Now maybe this makes some sense if you invested at the end of the Second World War and did not need the money for anything until you wanted to celebrate your 95th birthday this year (Exhibit 1). But if, like most investors, you invest for a goal, be it a new home, college for your children, or your own retirement, you’ll need the money sooner. And “sooner” could easily be during one of those nasty bear markets.

EXHIBIT 1: BULL AND BEAR MARKETS BY THE NUMBERS SINCE WORLD WAR II

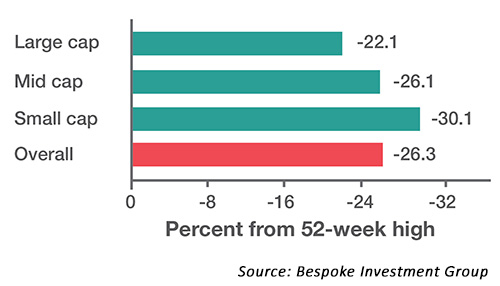

Look at just the last 12 months. Back in September, investors were worried because the S&P 500 had fallen about 10% from its May high point in a “market correction” (with an even steeper decline at the lows in February of this year). Yet that’s just one index—an index of large-cap, blue-chip issues. What about the average stock? No matter what index you choose from (including the large cap), the average stock lost more than 20% from its high this year, qualifying as a bear market by most definitions (Exhibit 2).

EXHIBIT 2: AVG. DISTANCE FROM 52-WEEK HIGH

Yes, they got it backward. History demonstrates, instead of “buy and hold,” it should at least be “buy and sometimes sell.” Selling could have helped most stockholders over the past 12 months.

Taking a longer-term view, we can’t forget that even the large-cap S&P 500 Index has collapsed more than 50% twice since the year 2000. On other indexes, the declines in that period were even steeper, in the range of 70% and greater. When faced with that reality, it is easy to understand why I think the idea of buy-and-hold investing is really a fallacy.

Not only does everyone sell sometime, but studies show that holding in the face of steep declines just isn’t within most investor’s capabilities. You may have heard of the yearly DALBAR studies of individual investor returns. Year after year—for more than two decades—it has been reported that the average investor returns are just a small fraction of stock index buy-and-hold returns.

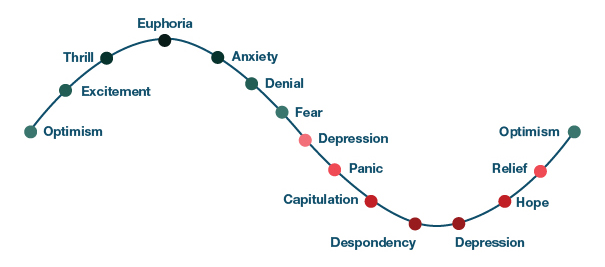

Typical investor emotions and actions are reflected in Exhibit 3.

EXHIBIT 3: THE CYCLE OF INVESTOR EMOTIONS

Investors buy when news is good and euphoria reigns at market tops—and only sell when the skies are darkest, usually capitulating as stocks are bottoming.

Academic studies demonstrate that this investor conduct finds its genesis in human behavioral biases, which spawned a whole new science called financial behaviorism. It also led to the development of active strategies that applied exacting standards and discipline to help investors weather the ups and downs of the financial markets. These strategies were carried out on the investors’ behalf to insulate them from the ill effects of those biases while seeking to avoid the worst of the market downturns.

Actively managed strategies are designed for full market cycles

Our company has been providing dynamic risk management in separately managed accounts since 1981. But after many decades of offering these separately managed accounts, it is obvious to me that investors have once again got it backward.

The accounts have delivered what they were designed to do. They provide disciplined trade execution to follow the exacting signals of time-tested strategies. They seek to smooth out market gyrations. Their first goal is to preserve capital. They do this not by simply holding a diversified portfolio of different asset classes, but by also being responsive to market movements. Investors get what they pay for: true actively managed accounts in which all the active management of their investments is done for them.

The “buy-and-hold-avoiding” activity is supposed to be dictated by the strategy signals. Instead, it is frequently supplied by the investor. Too often, they give up on the active strategy before it even encounters the bear market from which the strategies were designed to provide protection. These investors still respond to market moves to the up- or downside, ignoring the fact that the strategies they have invested in are already using well-researched lessons of market history to determine the proper response.

2015 was a good example. Maybe it was the perfect example.

Active management is about avoiding the worst performers and investing in the best performers. Last year, however, even the best performers only broke even. Stocks, bonds, and commodities all fell in 2015. International banking giant, Societe Generale, in a study of this unnatural correlation, pronounced 2015 to be the hardest year to make money in investing since 1937. Many hedge funds, including some of the best, lost money. Warren Buffet had one of his worst years, as Berkshire Hathaway lost more than 11 percent.

Active management feeds on volatility or trends. Yet there were no trends. The S&P 500 Index went back and forth over its break-even point a record 30 times.

Trend-following strategies were especially hard-hit by this on-again, off-again, non-trend-following market. After 2015 closed, one study showed that not one momentum period (or look-back parameter) would have made money last year. Fortunately, its author, David Varadi, also opined that such strategies are often mean reverting: If they perform badly one year, they tend to outperform the next.

Every strategy is designed for a full market cycle, which is about four years on average, encompassing a bull and bear market (20% up and down). Yet strategies designed for trending markets are many times abandoned by advisors and their clients (to my great disappointment) based on their performance during only a small, non-trending portion of the cycle.

In 2013, we saw the reverse. Strategies designed for sideways or down markets were being thrown overboard in the midst of a rally in a strong uptrend. Actively managed accounts are designed to provide the purposeful, disciplined activity for their investors, not the other way around.

Yes, sometimes I think, “They’ve got it backward!” Perhaps buy-and-hold investors should be more active, and investors in actively managed accounts should be less so.

Jerry C. Wagner, founder and president of Flexible Plan Investments, Ltd. (FPI), is a leader in the active investment management industry. Since 1981, FPI has focused on preserving and growing capital through a robust active investment approach combined with risk management. FPI is a turnkey asset management program (TAMP), which means advisors can access and combine many risk-managed strategies within a single account. FPI's fee-based separately managed accounts can provide diversified portfolios of actively managed strategies within equity, debt, and alternative asset classes on an array of different platforms. flexibleplan.com

Jerry C. Wagner, founder and president of Flexible Plan Investments, Ltd. (FPI), is a leader in the active investment management industry. Since 1981, FPI has focused on preserving and growing capital through a robust active investment approach combined with risk management. FPI is a turnkey asset management program (TAMP), which means advisors can access and combine many risk-managed strategies within a single account. FPI's fee-based separately managed accounts can provide diversified portfolios of actively managed strategies within equity, debt, and alternative asset classes on an array of different platforms. flexibleplan.com