How clients can find true happiness in their investing

How clients can find true happiness in their investing

Happiness is achieved through making progress toward a manageable goal. For investors, this means setting attainable and personalized goals consistent with their well-defined risk tolerance and risk capacity.

The Declaration of Independence sets out one of our “unalienable Rights” as “the pursuit of Happiness.” Yet there has been much debate over the centuries about what happiness truly is and how we can obtain it.

Psychologists tell us that happiness is a state of “subjective well-being” (SWB). It is a sense of feeling good about yourself and your life in whatever context you experience it. In that way, it is not based on one absolute definition but rather on each person’s subjective state.

Still, there seems to be agreement on what does not result in true happiness. For example, being rich and obtaining stuff, while satisfying in the short term, does not seem to lead to long-term happiness.

Tony Robbins, the great motivational speaker, says that happiness is progress. And many seem to agree with this, including the psychological community.

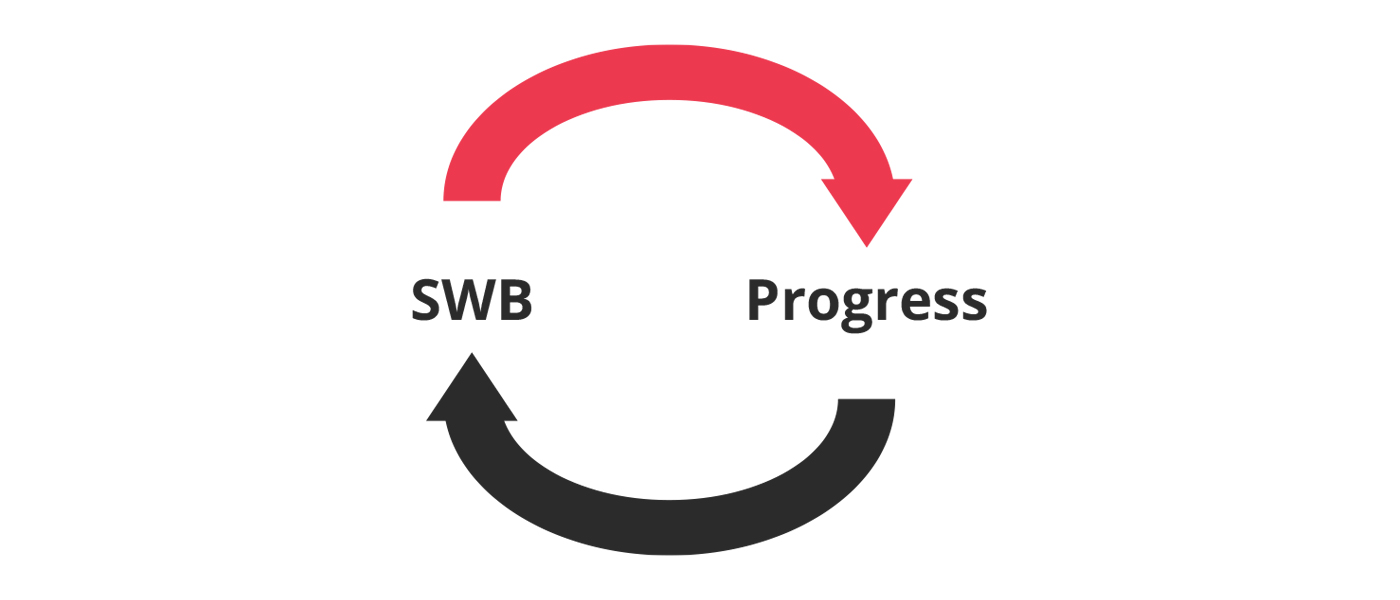

In a blog post for Psychology Today, Tim Pychyl explains that “progress on our goals makes us feel happier and more satisfied with life (our subjective well-being, SWB, increases).”

Further, he states, “The research on goal pursuit and well-being reveals an interesting cycle between progress on our goals and our reports of happiness and life satisfaction.” This cycle is shown in the following illustration.

While investing is just a small part of our life and our pursuit of happiness, the costs of modern life and funding our retirement income do make it an important part. So, how does Tony Robbin’s concept of happiness fit into the investing context?

We all seek progress in our investing—but in different ways. Many think it’s all about maximizing returns. But buying a lottery ticket probably is the ultimate way to maximize returns. Pay a dollar and you could receive an almost infinitely large return on your money. The only problem is, you can lose your entire investment and the odds are stacked against you.

So something more than mere returns must be assessed in determining investment progress. Risk and probabilities must come into the equation.

Many years ago, I co-wrote a paper for the Journal of Portfolio Management that demonstrated that in judging the efficacy of market timing you had to assess the returns earned in light of the risk taken. Risk-adjusted returns have now become the raison d’être for modern portfolio theory and the growth of liquid alternatives.

Progress in investing needs to be judged by the obtainment of the desired level of risk-adjusted returns.

The “desired level” is the subjective part. It is determined by one’s suitability profile. What level of risk can you live with and can you afford? It’s different for everyone, and it changes as one’s wealth increases and decreases and as the market incites emotions that fluctuate from fear to greed and back again.

This is why we regularly ask investors to use our suitability questionnaire to inform us of any changes in their profile over time or when they want to change strategies. Recently, one of my favorite financial commentators, Michael Kitces, conducted a webinar on “Rethinking Risk Tolerance.” As discussed in the financial press, the seminar made some very important points.

According to Kitces, financial advisors need to make use of suitability questionnaires in working with their clients. And these questionnaires must assess not only the risk capacity of clients but also their risk tolerances or attitudes toward risk.

The former is necessary to conduct the traditional financial-planning process and focuses on the amount and liquidity of client assets, income needs, and time horizons. It is essential to determine how much risk a client can absorb given the volatility of the financial markets.

Equally important, and not always measured, are their clients’ risk tolerances and attitudes toward risk. Attitude toward risk can determine whether a client can stick with the financial plan once it is developed and deployed.

We use quantitative analysis to supply the probability part of the “investment–progress equation.” We think of “probability” as the odds of winning. But essential to giving the “odds” any meaning is the concept of repeatability. Flipping a coin yields odds of 50/50. But the results are random.

With quantitative investing, one seeks a repeatable process that has an edge over the random outcomes of a coin flip. That does not mean that it will be right every time, but rather that it will be right more often than a coin toss, or generate more returns for the risk taken than a game of chance.

That’s why we develop computer-driven strategies. Having a computer follow a formula of commands yields a repeatable process. Being able to test that formula over history yields a probability for success.

More specifically, we believe a portfolio of rules-based, actively managed strategies can provide a multi-layered defense against market volatility. Using a combination of multiple strategies provides diversification of assets as well as enhancing overall effectiveness in different market environments. The “active” nature of the strategies means that the mix of aggressive and defensive asset classes and/or strategies is constantly changing and reacting with the vicissitudes of the market environment.

The psychological definition of happiness found that the pursuit of a goal was essential to the concept of progress. But Tony Robbins and others have found that pursuing just any goal won’t necessarily lead to happiness. Just as the mere acquisition of wealth and things is not likely to be satisfying, the pursuit of goals resulting from lowering one’s expectations isn’t challenging enough to evoke happiness.

Nor is requiring peak performance all of the time. That is simply not attainable. Life is made up of a series of highs and lows—as are the financial markets.

So simply making progress toward a goal is not enough to find happiness. Instead, we need to seek meaningful, manageable goals.

I often get the impression when talking to investors and advisors that their goal in turning to active managers is to find a strategy that gets all of the gains of the S&P while suffering none of its losses. That’s not a manageable goal. It will lead to disappointment, not happiness.

A more realistic outlook is to first realize that the markets regularly have peaks and valleys, and that a manageable goal is to end up with more dollars than you began with at the end of a full market cycle. Achieving this goal would leave you in a vastly better place than the buy-and-hold investor in the first decade of this century. An investor in the S&P 500 Index received less than breakeven for 10 years, even after enduring two full five-year cycles in the stock market. (See “Why 2020 is a rare chance to judge your active manager’s performance.”)

We help investors focus on the more meaningful goal by providing a chart of their time invested with us and our OnTarget Monitor in their quarterly statements. The latter takes the time horizon investors give us when they start with our firm and projects out the probable outcomes of the combination of strategies they are invested in.

In addition to this monitor, each quarter we track the performance toward the probable, attainable goal of each investor’s portfolio over the time horizon of their choice. Green means the portfolio is deemed OnTarget. Red means a change is in order.

Our firm offers over one hundred different strategies and suitability profiles, so a better fit for the current environment is always just a strategy change away.

***

The pursuit of happiness that is established as an unalienable right in the fabric of American governance is not a guarantee of happiness. As we have discussed, happiness is achieved through making progress toward a manageable goal.

For investors, that is not achieved by solely seeking returns, or by a Holy Grail methodology. Rather, it comes from setting attainable goals consistent with their subjective perceptions of the risk that they can comfortably and affordably take in building their investment portfolio. Progress, however, is not equal to relentlessly moving. Moving simply to gain a sensation of progress is not the answer.

True progress is made possible by investors knowing themselves (and documenting that knowledge using a suitability questionnaire) and by setting and monitoring their progress toward a goal that is personal to them and their portfolio.

Hopefully, these steps will lead your clients to the attainment of true investment happiness.

Jerry C. Wagner, founder and president of Flexible Plan Investments, Ltd. (FPI), is a leader in the active investment management industry. Since 1981, FPI has focused on preserving and growing capital through a robust active investment approach combined with risk management. FPI is a turnkey asset management program (TAMP), which means advisors can access and combine many risk-managed strategies within a single account. FPI's fee-based separately managed accounts can provide diversified portfolios of actively managed strategies within equity, debt, and alternative asset classes on an array of different platforms. flexibleplan.com

Jerry C. Wagner, founder and president of Flexible Plan Investments, Ltd. (FPI), is a leader in the active investment management industry. Since 1981, FPI has focused on preserving and growing capital through a robust active investment approach combined with risk management. FPI is a turnkey asset management program (TAMP), which means advisors can access and combine many risk-managed strategies within a single account. FPI's fee-based separately managed accounts can provide diversified portfolios of actively managed strategies within equity, debt, and alternative asset classes on an array of different platforms. flexibleplan.com