Creating investment strategies for real people

Creating investment strategies for real people

Each spring for the last 20 years, DALBAR, Inc., has released its Quantitative Analysis of Investor Behavior (QAIB) study, and each year the conclusion is much the same. According to the study, individual investors underperform the market’s return based on the flow of monies in and out of mutual funds. In frustration, DALBAR’s 2014 study states, “Attempts to correct irrational investor behavior through education have proved to be futile. The belief that investors will make prudent decisions after education and disclosure has been totally discredited.”

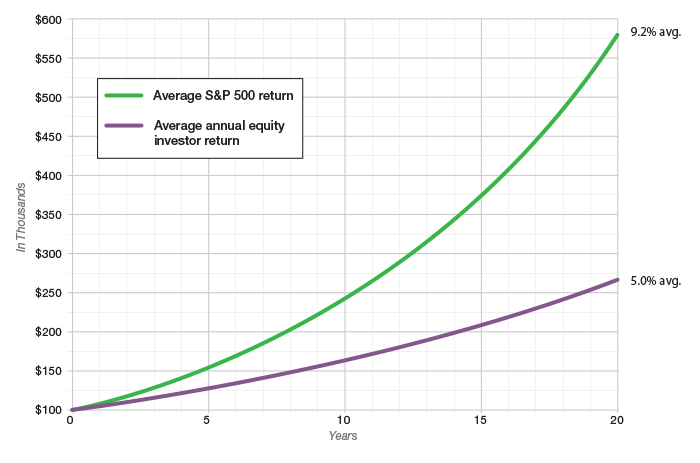

According to QAIB, “The greatest losses occur after a market decline. Investors tend to sell after experiencing a paper loss and start investing only after the markets have recovered their value.” The result, says DALBAR, is an average annual equity investor return over the last 20 years of 5.0% compared to 9.2% for the S&P 500, a difference of more than 45%.

Compounded over 20 years, such a return differential will have a huge effect on an investor’s bottom line, as can be seen in the chart.

20-year compounded return

But before one uses DALBAR’s results to berate investors for underperformance in their mutual fund investments, perhaps a better use of the data is to ask why real people buy and sell at the wrong time and how portfolios can be better designed to help real people succeed.

DALBAR’s results have been well-publicized, along with comparable studies conducted by other entities, including Morningstar. During the last two decades, a whole new generation of investors has entered the stock market, a generation that one would expect to have been exposed to the DALBAR message. Yet, based on the results of the studies each year, little, if any, change has been seen in investor behavior. “Individual investors are brilliant at mis-timing the markets,” says DALBAR’s president, Louis Harvey.

Rather than wasting time trying to change the individual investor’s behavior, it makes more sense to accept that real people tend to buy high and sell low. Investor behavior is remarkably consistent over time. Once you accept that parameter, the next step is to develop investment portfolios that provide the incentives investors need to stay with the portfolio and strategy over the long run. This is where active management has a very important role to play.

Rather than wasting time trying to change the individual investor’s behavior, it makes more sense to accept that real people tend to buy high and sell low.

The science of behavioral finance is extraordinarily useful in building portfolios for real people. Behavioral finance helps us understand why behaviors happen and how people make decisions. But first you have to step beyond the premise that it explains why people act “irrationally.”

Actions are typically judged as irrational when they run counter to the calculated probabilities of events, especially rare ones. For the individual, rationality or irrationality can only be determined in hindsight. For example, the incidence of esophageal cancer is only 0.36% of the population. If you have esophageal cancer, it is 100%.

One of the most important principles of behavioral finance is loss aversion. Loss aversion refers to people’s tendency to strongly prefer avoiding losses to acquiring gains. Some studies suggest that losses are twice as powerful, psychologically, as gains. The degree of loss aversion is influenced by perceived risk—and perceptions of risk are relative. They change over time and in response to how current circumstances are filtered through prior experience, the influence of opinion leaders within the individual’s life, life events changing an individual’s financial outlook, and other factors.

Mental accounting also plays an important role in investor behavior. Mental accounting is the tendency for people to separate their money into different accounts based on a variety of subjective criteria, like the source of the money and intent for each account. For example, a family may have retirement accounts, college accounts, vacation accounts, Christmas savings accounts, emergency accounts, and so on. Even though the aggregate value of these accounts is the same, different risk parameters and loss tolerances are assigned to the individual accounts.

An active investment strategy that seeks investor commitment over the long term needs to recognize the influence of loss aversion and mental accounting. If a portfolio declines in value as a result of a bear market, loss aversion kicks in. At the behavioral finance level, it doesn’t matter to the investor that the historical long-term trend of the market has been up, or that this particular market will probably recover as well. It’s like being told the chance of cancer is minimal when one is in the midst of treatment for cancer.

How can an active-management investment approach address these behavioral finance issues?

1. Accept that people worry about losing their money. Build into the strategy risk-management tools to limit losses in a down market or an underperforming investment, and indicators that help move funds into a rising market early in the cycle.

2. Use multiple strategies to accommodate the tendency for mental accounting. If the client is more comfortable dividing his account by investment objective and time frame, there is the potential to enhance overall performance by using different risk-return objectives throughout the portfolio. This may also give advisors an opportunity to attract more of the individual’s overall investment.

3. Make certain the investor understands the approach sufficiently and that market volatility doesn’t rattle their confidence in the investment strategy. Active management is built to perform over a full market cycle of both bull and bear.

Active management is built to perform over a full market cycle of both bull and bear.

By creating quantitative rules for when a portfolio position is bought or sold, the active investment manager can help overcome the typical investor behavior of buying high and selling low, taking emotion out of the equation. Not every buy and sell decision will be optimal, but based on studies by DALBAR and other entities, there’s considerable room for improving investor returns within the framework of the market. And the potential for active management to add alpha—return in excess of the market—offers an additional benefit that can become quite significant in compounded returns over time.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Proactive Advisor Magazine. These opinions are presented for educational purposes only.

Linda Ferentchak is the president of Financial Communications Associates. Ms. Ferentchak has worked in financial industry communications since 1979 and has an extensive background in investment and money-management philosophies and strategies. She is a member of the Business Marketing Association and holds the APR accreditation from the Public Relations Society of America. Her work has received numerous awards, including the American Marketing Association’s Gold Peak award. activemanagersresource.com

Linda Ferentchak is the president of Financial Communications Associates. Ms. Ferentchak has worked in financial industry communications since 1979 and has an extensive background in investment and money-management philosophies and strategies. She is a member of the Business Marketing Association and holds the APR accreditation from the Public Relations Society of America. Her work has received numerous awards, including the American Marketing Association’s Gold Peak award. activemanagersresource.com