How do you anticipate the unexpected?

How do you anticipate the unexpected?

Specific market events are usually unexpected at the time they occur—yet the possibility of their occurrence is almost always known in advance.

It always seems to begin the same. A “news flash” scrolls across the lower portion of our TV screens. Or the music on the radio trumpets a change is coming.

On August 24th of this year, early birds watching or listening to the TV saw these types of alerts, while others heard about it shortly after they awoke. A 6.0 earthquake rocked Napa Valley, disturbing the peace and quiet, the serenity that marks one of America’s most beautiful regions. Windows on Napa’s Main Street exploded into a shower of glass, rubble fell from the fronts of buildings, and mobile homes burst into flames. Hundreds of people were injured, many very seriously, and there was at least one fatality directly related to the quake.

It was a scene unique to the Napa area that weekend, yet familiar to us all. Every community has had its disasters. While they are all of varying proportions, they share some of the same characteristics. First and foremost, our hearts, America’s communal sense of empathy, always go out to every community experiencing the loss that these disasters bring.

Second, it is always the case that the specific disasters were unexpected at the time they occurred. Yet, almost paradoxically, the possibility of their occurrence was also almost always known with a certainty in advance.

PAST MARKET DECLINES

While the Napa earthquake could not have been predicted with current technology, we know with a certainty that sooner or later the “big one” will hit the West Coast (that’s 7.5 to 9 on the Richter scale versus 6.0 for this one). Although we cannot predict precisely when or where tornadoes will touch down, we know with a certainty that hundreds will occur across the South and Midwest each year. And, while models keep getting better and better, we can’t tell precisely where hurricanes are going to go ashore, yet we know that at least one will wreak havoc somewhere along our shoreline each year.

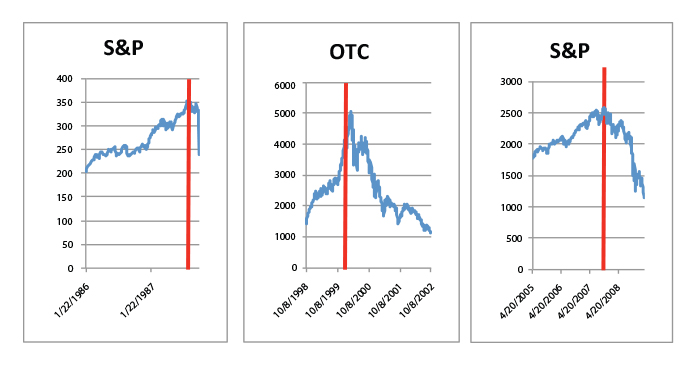

Of course, this is no different than what we have to deal with in the stock market (or with most financial asset classes, for that matter). Check out the three graphs of past stock market values. At the point where each red vertical line intersects the graph, each price line was hitting new all-time highs. But could you tell at that point that the bottom was about to drop out of stocks?

For more than a century, stocks have undergone these precipitous declines every five to seven years, on average. We know with a certainty that they will keep occurring, although no one knows precisely when.

It is encouraging, however, that active money management has been able to provide some shelter during the periods noted above. Active managers have the ability to move in and out of markets or asset classes and have demonstrated the ability to adapt to changing market conditions—unlike passive buy-and-hold approaches to investing.

What are we doing in anticipation of the next bear market?

Each of these market declines was very different from the other. In the 1987 example, stocks fell because of tightening operations of the Federal Reserve that were not widely recognized in advance—though some key market-timing indicators gave advance warning. In the second crash, the decline occurred in waves and hit different sectors at different times—allowing active strategies to rotate from the hardest-hit sectors to stronger ones.

Finally, the last financial crisis was not widely anticipated, and most assets fell together when stocks collapsed. Protection was only achieved by having actively managed strategies with a defensive plan that automatically went into effect as prices fell, plus being widely diversified not only on an asset class basis, but also on a strategy basis.

In 2014, the financial markets have hit many new all-time highs with shallow corrections along the way. Yet you might ask, “What are we doing in anticipation of the next bear market?”

Some say the bear is right around the corner—if only because this bull market is growing old. If you count the March 2009 low as the bottom for stocks that preceded the current rally, the bull market has lasted more than five and a half years. This is longer than the average bull market.

Although this argument has been circulating Wall Street for some time, there is a different view possible. A bear market is traditionally defined as a decline of 20% or more in the major indexes. And it is true that the S&P 500 has not fallen 20% since March 2009, but in 2011, the index did fall 19.38% from market close to market close, and on an intraday high to intraday low basis the decline was 21.58%.

If we count the end of that decline as the completion of a bear market, we now have a starting point of October 4, 2011, as the beginning of the current rally, and the current rally is then of shorter-than-average duration. This suggests that that the stock market rally may go on much longer than many anticipate. In addition, the primary bullish trend line has held on each downturn, suggesting that the primary trend remains upward pointing toward “higher ground.”

However, what if this market situation changes dramatically?

And what if this is neither a 1987-type decline (forecastable by some indicator) nor a 2000-2002 meltdown (tipped off by cascading momentum moves in different asset classes)? If it is, instead, a repeat of 2007-2008 or is something totally unexpected, what do we fall back on then?

We have to depend on the defensive plans of actively managed strategies.

That’s when we have to depend on the defensive plans of actively managed strategies and on a strategic diversification line of defense. Many strategies are based on the concept of targeting a level of risk and restraining portfolios to the resultant targeted maximum loss levels, by diversifying among less-correlated asset classes and strategies.

Everyone seems to nod their heads when I say that you need to have different types of assets and strategies in your portfolio to protect yourself from the unexpected. Yet, few seem to realize that to do that you have to own some assets or strategies in your portfolio that are not going up when everything else is.

No diversifying strategy or strategy incorporating alternatives goes up all the time—a difficult concept for many to understand or accept, but one that is fundamental to our approach.

The next significant market downturn may be impossible to predict as to cause, severity, and timing, but it is a fair assumption—as with those natural disasters—that there will be another one. True diversification and actively managed strategies to handle risk are excellent ways to protect portfolios from the “expected” arrival of the “totally unexpected.”

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Proactive Advisor Magazine. These opinions are presented for educational purposes only.

Jerry C. Wagner, founder and president of Flexible Plan Investments, Ltd. (FPI), is a leader in the active investment management industry. Since 1981, FPI has focused on preserving and growing capital through a robust active investment approach combined with risk management. FPI is a turnkey asset management program (TAMP), which means advisors can access and combine many risk-managed strategies within a single account. FPI's fee-based separately managed accounts can provide diversified portfolios of actively managed strategies within equity, debt, and alternative asset classes on an array of different platforms. flexibleplan.com

Jerry C. Wagner, founder and president of Flexible Plan Investments, Ltd. (FPI), is a leader in the active investment management industry. Since 1981, FPI has focused on preserving and growing capital through a robust active investment approach combined with risk management. FPI is a turnkey asset management program (TAMP), which means advisors can access and combine many risk-managed strategies within a single account. FPI's fee-based separately managed accounts can provide diversified portfolios of actively managed strategies within equity, debt, and alternative asset classes on an array of different platforms. flexibleplan.com