Barron’s said in its analysis of the report, “Consumer spending is the central driver of the economy but is slowing. … [However,] it’s the resilience in the consumer, despite a soft holiday season, that headlines this report.” This reflects that personal consumption, while lackluster, contributed greatly to what GDP growth there was.

A central question remains: With consumer spending slowing down, what exactly is happening with all of the hoped-for household savings attributed to lower gasoline prices at the pump?

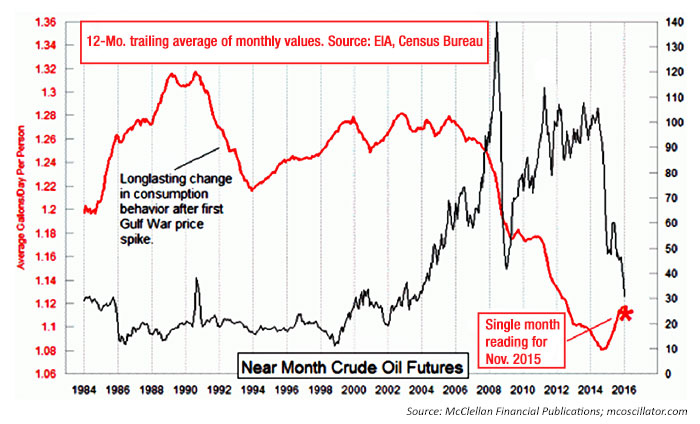

US PER CAPITA DAILY GASOLINE CONSUMPTION

Analyst Tom McClellan, in his weekly feature “Chart in Focus,” recently addressed this point:

If consumers are spending less of their money on gasoline, then they ought to have more to spend on other stuff, or so goes the reasoning. So why is it not working?

The EIA publishes data on consumption for a variety of energy products, including gasoline. In November 2015 for example (the most recent month for which there are data), Americans consumed gasoline at a rate of 358 million gallons per day. The 12-month average is 360 million gallons.

That sounds like a really large number, but when you realize that there are roughly 322 million resident Americans, that works out to 1.11 gallons per day for every American.

Looking at the math, if the price of gasoline drops from $3.00 to $2.00 (round numbers to make the math easier), that means an extra $1.11 in your pocket every day, assuming you are the average man, woman, and child in America.

Aggregating all of those savings, a $1 drop in gasoline prices amounts to around $10.8 billion of supposed stimulus in the form of consumers keeping more of their own money. That’s $1 multiplied by an average of 360 million gallons per day, times 30 days in an average month. Now, $10.8 billion per month is a pretty big number, but it is nowhere near the $85 billion per month that the Fed was pumping into the banking system during QE3, for example. Still, $10.8 billion per month ought to do something for stimulus, right? Yes, of course, but that is unless it gets eaten by monsters.

Mr. McClellan goes on to identify two of those “monsters”: (1) the continuing acceleration of health-care premium costs (anticipated to rise 12.6% in 2016), and (2) the growth of the federal tax burden on individuals and the economy, now at 18.1% of GDP. He concludes: “The magnitude of the savings is just not enough to outweigh those stronger forces. It would not even be enough if gasoline [were] free. And that’s the big takeaway message.”

Editor’s note: Many thanks to Tom McClellan for sharing his analysis. The “Chart in Focus” feature is free with sign-up and can be found here.