Fiduciary responsibility in a world where industry bashing is the norm

A grandfather’s warning

The son of a close friend is a graduate student in New York City. His grandfather—tongue in cheek, but not totally—admonished him that if he ever pursues a career in finance, he will be disowned. Of course, there is always some truth in jest. This got me thinking how not that many years ago this grandfather would have been proud to say his grandson was part of Wall Street. How did this perception change? More important, how can we in the profession right the ship?

Battling the bashing of Wall Street

There will always be a very small cast of characters, such as Bernie Madoff, who will diminish our industry. But today so many of our country’s woes are being attributed to big business in general—and Wall Street in particular. Incendiary comments made in the presidential campaigns, the overall atmosphere in much of academia, and blockbuster books and movies such as “Flash Boys: A Wall Street Revolt” and “The Big Short” only magnify this perception.

“The Big Short” presented many sophisticated financial concepts—such as the use of collateralized debt obligations and credit default swaps—that were challenging for even those with a financial background to fully comprehend. These concepts, quite frankly, were beyond the reach of most viewers. The movie placed most of the blame for the financial crisis on Wall Street. Whether or not viewers fully appreciated the confluence of other parties or policies that led to the crisis and subsequent recession, they clearly left the theater feeling anger and disdain for anyone who makes a living on “Wall Street.”

Bashing Wall Street is in vogue today, and it is coming from many directions. We cannot underestimate how this criticism could affect our careers, the future growth of our industry, and the recruitment of new advisors to the business. In fact, my friend admitted that “The Big Short” influenced not only his father’s perceptions, but his own as well. This led to a lively discussion and a lot of contemplation on my part.

Wall Street’s two sides

After a crisis, particularly one as significant as the subprime debacle, it is natural to assign blame. From a psychological point of view, it is easier to hold one group accountable than attribute responsibility to many, because this makes the problem seem less widespread and the remedy more achievable.

My argument to my friend was three-fold. First, there is a lot of blame to go around, and not just on Wall Street (which can easily lead to an hours-long discussion). Second, “Wall Street” as a term is uncharacteristically broad—it tends to link small, independent family-wealth advisors and many others in the industry with “too big to fail” international investment-banking organizations. In my humble opinion, most of the negative perceptions around the industry, rightly or wrongly, have been chiefly influenced by the actions of these large institutions.

Third, most people not employed in the industry do not fully understand that Wall Street has two sides—commonly known as the sell side and the buy side. In broad terms, the sell side focuses on underwriting, making a market for, and selling securities and other asset classes to the public and to institutions. The buy side, again in simple terms, focuses on buying and managing investment vehicles for the public and institutions.

I think much of the confusion around the industry, and many of the perceptions, emanate from what some consider an inherent conflict of interest when both buy- and sell-side operations are housed within the same large institution. In theory, one side acts as a broker, and the other side should act as a fiduciary guarding the best interests of clients. This is a decades-long debate—well beyond the scope of this discussion—but one that contributes mightily to today’s atmosphere of distrust around the industry.

As an analogy to further clarify the distinction between the sell side of the investment house and the buy side, let’s consider the various functions and loyalties of a large real-estate conglomerate that has two divisions. One acts as a broker and is compensated through commissions, while the other offers fee-based consulting. All of us understand that the real-estate broker is only compensated if a transaction is effectuated. While we might select the real-estate broker based on reputation, compatibility, and confidence, we certainly appreciate the sales nature of the job. In this way, we adjust our expectations and accordingly ascribe a code of ethics in terms of the broker’s role. On the other hand, if we hire the consulting arm of the real-estate firm to conduct a feasibility study for a property that we own and we are seeking an analysis of its highest and best use, then we would hold that division of the company to a much different and higher standard.

Although the standard of care and ethical expectations for the different divisions within the real-estate industry seem to be reasonably well understood and appreciated, the same is not true for Wall Street firms. We would unlikely chastise the real-estate broker for representing the seller of a home on one side of the street while simultaneously representing a buyer of a home directly across the street.

We expect real-estate brokers to work with both buyers and sellers of unrelated properties. Therefore, we do not accuse them of having a conflict of interest because we accept this as the nature of a transactional broker. Yet, when a sell-side broker at an investment bank sells securities to one purchaser and buys securities for an in-house account or an unrelated purchaser, we feel a line has been crossed. So much of the distrust and vitriol extended to Wall Street, I contend, results from a misunderstanding of these two sides of investment banking and their different standards of care.

The expectations of fiduciaries—and their clients

There is a lot of focus today on the new regulations from the Department of Labor that purport to “rein in Wall Street” by requiring investment advisors dealing with client retirement accounts to act like the buy side of the industry as a fiduciary. While on the surface this seems reasonable, and I personally prefer to engage on this basis, it is important to remember that to truly act as a fiduciary and to be held to that standard, the advisor must be viewed by the client as a highly trusted confidant—and not just someone to go to for transactional services.

To truly act as a fiduciary, an advisor should have extensive knowledge about a client’s personal situation in every way reasonably possible. The advisor should also know the client’s net worth and estate and tax planning, where the client’s other investments are held and how they are titled, and numerous other considerations.

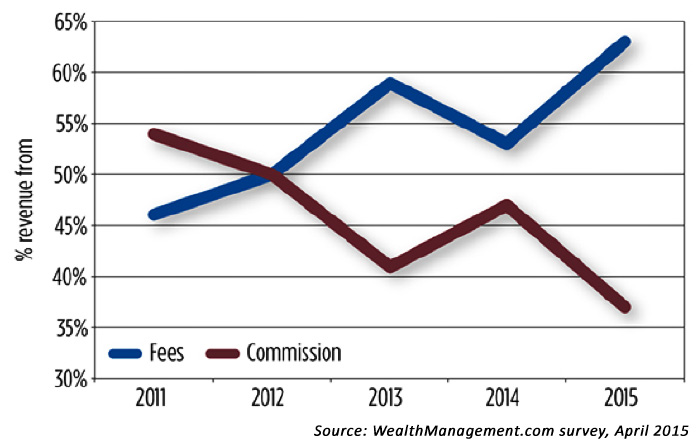

Not every client wishes to reveal all of this sensitive data. Many of us seeking to act in the client’s best interests as fiduciaries are at times told by a client that they want to “try us out” by investing in one of our suggestions before making a larger commitment that would enable us to serve them beyond a product. Other clients prefer to speak to multiple advisors and then pick and choose what investment ideas they follow. There is an inherent contradiction if regulators (and some clients) want to hold an advisor to the highest standard of care and associated liability whether or not the advisor is being treated as a true fiduciary. Outsourcing at least a portion of an advisor’s assets under management to fee-based money management can minimize this predicament and further support the fiduciary standard. (Editor’s note: See the following chart for one study’s take on the growth of fee-based advisor compensation.)

GROWTH OF FEE-BASED VS. COMMISSION-BASED ADVISOR COMPENSATION

The bottom line for me is that I have absolutely no issue being held to a high level of accountability in my practice—that is the fundamental premise I have worked from for several decades. I only suggest that this is a shared responsibility, and expectations for client “accountability” should similarly be acknowledged. My hope is that our industry takes the initiative, speaks up, and moves to clarify the appropriate roles on both sides of the advisor-client relationship.

***

Our industry needs to do a better job educating the public on the benefits of working with a financial advisor. We have a valuable role to play in helping clients achieve their desired financial objectives, especially in the context of ever-longer life expectancies—a retirement challenge most Americans are currently ill-prepared to face on their own.

I remain proud of the work I do for clients every single day and would be honored to have my children or grandchildren follow in my footsteps.

Gregory Gann has been an independent financial advisor since 1989. He is president of Gann Partnership LLC, based in the Baltimore, Maryland, area. www.gannpartnership.com

The opinions voiced in this material are for general information only and are not intended to provide specific advice or recommendations for any individual. The opinions expressed in this material do not necessarily reflect the views of LPL Financial. Securities offered through LPL Financial, Member FINRA/SIPC.