Why it is critical to understand your clients as emotional beings

Why it is critical to understand your clients as emotional beings

Advisors will benefit from a sophisticated and nuanced understanding of the various emotional and psychological factors that drive our clients’ thinking about investing, wealth management, and estate planning.

When it comes to forging strong client relationships, how much effort do you make to truly get to know your clients as people?

I’ve been working as an investment analyst, portfolio manager, investment coach, and wealth-management advisor now for more than 25 years, and if there’s one thing I’ve learned over time it’s that people—individuals, couples, and families—are both complicated and conflicted when it comes to issues of money, retirement, wealth management, and investment planning.

There are many reasons for this.

First, I believe that people’s views about money (and security) can usually be traced back to early life experiences of pain and loss associated with family, friends, relationships, and love. These formative experiences deeply influence the development of a person’s “emotional template” and shape how they think about their assets, risk-taking, and their ability (or inability) to control people and events later in life. For example, the person who experiences significant personal or emotional loss early in life may, later in life, display little trust in others, a high need for security and control, and/or little tolerance for risk-taking when it comes to making investment decisions. I’ve often seen such dynamics at play when I work with certain clients or meet new client prospects for the first time.

Second, people’s attitudes about money can be profoundly shaped by what their parents, grandparents, or other authority figures told them about it when they were growing up. Was your client encouraged, from an early age, to be frugal and save for a rainy day? Or did he or she grow up as the product of profligate parents? People often carry such “messages” about money with them into their adult lives.

Third, some people’s attitudes and feelings about money are shaped based on whether they grew up with wealth or achieved it for themselves. Hence, the popular, if somewhat simplistic, image of wealth creators as world-class penny-pinchers and wealth inheritors as world-class spendthrifts.

Fourth, other people’s views about money are influenced by family dynamics, personal beliefs, college professors, religious faith, and philosophical convictions. Who made the greatest impression on your client as a child or young adult?

Finally, people’s attitudes about money (and risk-taking) are frequently driven by primal emotions like fear, greed, guilt, discomfort, or even a sense of inadequacy. Such emotions can literally sweep over them, immobilizing them from making clear and rational choices or acting in their best interests at critical times.

Yes, when it comes to money, people are complicated.

Our clients live in two different worlds

In my experience, most people have dual personalities when it comes to investing. The charming, composed, and rational individual who meets with you in your office when the markets are normal to discuss plans for their portfolio can suddenly morph into someone driven by fear when the markets deteriorate or by giddy, ambition-fueled greed when the markets soar to new heights.

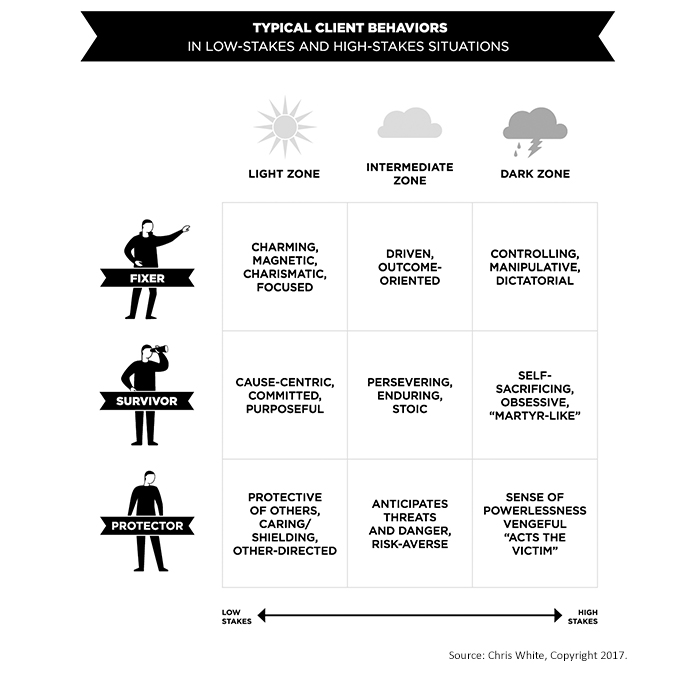

How do I know this? Because I’ve seen the scenario play itself out again and again when the markets go from steady to volatile. It occurs because every investor lives in two worlds, a low-stakes world where reason and intellect apply (the “light side”) and a high-stakes world in which a person’s “dark” or shadow side can appear, driven by raw and unrestrained emotions such as fear, greed, ambition, and powerlessness. (See Figure 1.)

Because emotions and psychology are always intertwined with the investing process, I believe it’s incumbent on us, as advisors, to develop a sophisticated and nuanced understanding of our clients as emotional and psychological “systems.” How does one do this?

Over the course of my career, I’ve found that there are different kinds of clients, each of which displays specific attitudes and behavioral traits. For a long time, I struggled to devise a typology with which to understand and organize my observations of such characteristics, and to categorize clients (without dehumanizing them) so I could develop appropriate strategies to deal with each type.

Then, I discovered the work and theories of Dr. David Kantor, a psychologist and major thought leader in the fields of social psychology and group dynamics. Kantor’s research on personality types has been highly useful to me in decoding human motivations and behavior, understanding how people (clients) act in different situations, and organizing my understandings about people into a practical taxonomy.

Kantor believes a person’s view of the world is based primarily on the early life experiences they have relating to love, loss, joy, and pain. An individual’s personality is formed as the result of the childhood “stories” we create to explain such experiences to ourselves. These stories become foundational in our development, first as children, then as adolescents and mature adults. The life “lessons” our stories contain (about love, loss, pain, hurt, power, powerlessness, etc.) become part of the operating code of our psyches and shape how we see ourselves in the real world.

Three distinct and identifiable personality types

Kantor further contends that people’s behaviors and personality traits can be categorized into three specific personality types: the “Fixer,” the “Survivor,” and the “Protector.” The Fixer is a risk-taker who’s highly motivated by a will to win in all they do. The Survivor is motivated by causes and purposes beyond themselves. The Protector is motivated by a deep-rooted concern for the welfare of others.

Kantor’s model of personality types is highly adaptable to the work we do with clients. In fact, I’ve adapted his model and applied it to understanding the behavior of my clients in both low-stakes (everyday) and high-stakes circumstances (e.g., periods of market volatility.) Not surprisingly, I’ve discovered that each type has distinctly different investment motivations and each responds quite differently as circumstances move from low to high stakes. This has big implications for the active management approach we take in working with each type.

The Fixer

The Fixer client is a strong-willed, highly risk-tolerant individual who’s focused on making money from their investments, typically in the near term. As a personality, the Fixer is “all business” and is likely to take a highly transactional style in their interpersonal dealings with you, their advisor. That’s because the Fixer is focused on winning the investment game at all costs.

Under normal (low-stakes) circumstances, Fixers can be charming and have the ability to fill a room with their “force-of-nature” personality. Not surprisingly, many CEOs are Fixers because they have a “can-do” attitude and because they’re very focused on getting things done.

That said, when the stock market goes south, watch out! The Fixer can undergo a rapid personality change, turning into a controlling and argumentative person who questions your professional competence and even berates you and your firm for the way you’re handling their investments. Because aggression is at the heart of the Fixer’s personality, Kantor describes them as operating in the “domain of power.”

In my estimation, the Fixer’s need for control—to operate in “the domain of power”—likely has its roots in that individual’s early life, when they faced some large obstacle or challenge to overcome or when they felt that the events of their life were out of control. As an adult, events such as a roiling stock market serve as a psychological trigger to the Fixer, who becomes obsessed with the idea of prevailing under adverse circumstances.

To Fixers, the possibility of financial loss is not only unacceptable, it is anathema. Thus, if you find yourself dealing with a Fixer client, take a few deep breaths and stay calm. While Fixers are sometimes resistant to taking advice from advisors, any losses they experience from following their own instincts can make them receptive to your investment suggestions. So, if market conditions become volatile, engage the Fixer directly using undisputed facts to suggest near-term courses of action. Your quiet self-assuredness in such moments will help reinforce trust and respect with the Fixer and remind them of why they sought you out as their advisor in the first place.

The Survivor

While Fixers have intense, hard-charging personalities and are determined to win at any cost, Survivors tend to be lower-key and more philosophical and idealistic in their attitudes about investing. They’re often mission-driven in their approach to the investment process, focused on causes, ideals, or goals beyond themselves and beyond pure monetary gain.

Kantor says Survivors operate in the “domain of meaning.” The Survivor’s search for “meaning” in all they do (including how they invest) most likely develops as a personality trait from seeing someone important to them (e.g., a parent) committing themselves to a worthy cause—or, as a child, observing an incident of injustice or learning firsthand about the pain and suffering of others. In response, they decide to dedicate themselves to noble and virtuous goals. They take this notion of “meaning” and life purpose with them into adulthood, where it permeates their thinking about their wealth and how to invest and use it, not just for their benefit, but for the benefit of others.

Unfortunately, the Survivor’s idealism can get in the way of them making prudent, financially beneficial decisions about investing. Indeed, when the markets go south, the Survivor can become stoic, their idealism can turn to intransigence and keep them from making changes to their portfolio to minimize adverse market exposure.

Because they’re essentially “risk-indifferent,” Survivors often greet stock market setbacks with a grim determination to stay the investment course they’re on. If you find yourself counseling a Survivor client when the market becomes volatile, he or she may be determined to hang on to a certain stock, even when you know they should get rid of it to help them rebalance their portfolio. At such moments, you must nudge the Survivor client to consider new options to safeguard their investments and to limit their financial exposure in a volatile stock market. But don’t put all of the emphasis on financial gain. Instead, remind them of their personal values and wealth-management philosophy, and how making portfolio adjustments can honor both philosophical and financial priorities.

The Protector

Finally, there are clients whom I describe as Protectors. Protectors focus more on others than on themselves when talking with you about investments and financial planning. Protector clients are easy to spot. When markets are calm, they talk animatedly with you about how they want to use their wealth to benefit others—for example, spouses, partners, children, and grandchildren—or to benefit specific causes and organizations. They’ll also talk enthusiastically about issues such as “life legacy” and establishing mechanisms for periodic gifting to the next generation.

In my opinion, the altruism, compassion, and concern that Protectors show for others—and that is apparent in their thinking about investing and wealth management—are core personality traits that develop early in their lives, perhaps as the result of a grievous personal loss; or because of parental influences, family values, moral epiphanies; or the “messages” they receive about money and wealth from teachers and other authority figures.

Because of their attitude of stewardship and guardianship of others, Kantor describes Protectors as operating in the “domain of affect.” Despite their concern for others, however, Protectors are the most risk-averse of the client types. When market conditions become volatile, the Protector can suddenly feel they have no control over what’s happening around them and may assume the stance of the victim. Once they do, they find it hard to make decisions to shore up their portfolios and to safeguard their investments. Consequently, as their advisor, you may need to calm their fears, help them take charge of their situation, explore options, and lay out a course of action to help them navigate through times of extreme market volatility. Here, the factor of trust between client and advisor becomes paramount.

FIGURE 1: HOW INVESTOR BEHAVIOR CHANGES UNDER STRESS

All clients are different, but…

You may be asking yourself, “How do I determine what type of client I’m working with?” You won’t likely identify a person’s hero type the very first time you meet them as a prospect or client. Hero types are rarely so obvious. Moreover, a person’s hero type typically doesn’t become fully evident until the stakes become high.

Initially, however, you can listen for clues and look for traits that will enable you to begin developing a profile of what that person’s hero type is likely to be as stakes grow higher. It begins by asking clients questions not only about their specific financial goals but also about their investment values, and the purpose they see their wealth serving for themselves and others.

Obviously, the client typology I’ve described here isn’t meant to be a “shake and bake” recipe for dealing, in formulaic ways, with the clients you counsel. After all, every client is unique. That said, in my experience, Fixers, Survivors, and Protectors are the three major client personality types you’re likely to encounter in your work as a wealth counselor. Consequently, you can use this client typology framework to develop accurate personality profiles of your clients and to devise active management strategies custom-suited to each client’s unique financial goals, psychological traits, personal goals, and risk-tolerance.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Proactive Advisor Magazine. These opinions are presented for educational purposes only.

Chris White is a longtime wealth advisor and author of “Working with the Emotional Investor: Financial Psychology for Wealth Managers” (Praeger, 2016). He is a member of the CFA Institute, the Boston Security Analysts Society, and the Boston Economics Club. www.chriswhiteauthor.com

Chris White is a longtime wealth advisor and author of “Working with the Emotional Investor: Financial Psychology for Wealth Managers” (Praeger, 2016). He is a member of the CFA Institute, the Boston Security Analysts Society, and the Boston Economics Club. www.chriswhiteauthor.com