‘Time in the market’—without risk management—works against investors

‘Time in the market’—without risk management—works against investors

The longer one is invested, the more bear markets one will encounter. For buy-and-hold strategies, risk does not decrease with time in the market, it increases.

When the market reaches new highs and murmurs that it may be overvalued begin to make the rounds, there’s one topic you can count on encountering frequently in the financial media and blog postings from investment firms—the benefit of “time in the market” versus “timing the market.” There were many examples of this trend over the past year, including the following:

- Seeking Alpha, 2/7/17—“The longer you stay in the market, the better will become your investment return. But you don’t have to believe me—you only have to be able to read graphs of various financial studies.”

- Bloomberg, 5/1/17—“Timing may appear to be almost everything in the stock market, but we still believe in time. The top 100 performing days of the past two decades account for 60 percent of the market’s total return over this period. Imagine if in your timing wisdom, you missed those 100 trading days—or vice versa.”

- Forbes, 11/21/17—“Years of historical stock return data (along with our top-of-table long-term newsletter performance ranking, despite always being near fully invested) show that time in the market is far more important than market timing.”

If an investor has no plan to manage market volatility, then “buy and hold” may well be their safest and surest path to respectable returns. That assumes they stick to their plan perfectly for many years, not letting emotion and behavioral bias interfere.

On the other hand, one wonders how much the promotion of buy-and-hold investing is actually an effort to assure that there are plenty of losers to provide profit for professional traders. Only in rising markets is there anything close to a win-win situation for buyers and sellers. Even then, investors who sell too early give up gains to those who purchase their positions. In falling markets, those investors first to the door have the best odds of preserving their profits and having funds available at market bottoms to leverage their returns. It is to the advantage of professional investors to “promote” the wisdom of buy and hold for Main Street investors.

Is that too cynical a view of the “time in the market” argument? Perhaps, but there’s a lot wrong with this argument that doesn’t make it into the news.

What’s wrong with the ‘time in the market’ argument?

The basis of the “time in the market” argument is that the longer one is fully invested in the market, the less chance there is of suffering the loss of one’s investment. After all, financial markets have an upward bias over the long run. Market tops and bottoms are very difficult to call with any precision, and missing the “best days” of the market will dramatically lower returns. By bailing out of the market, paper losses are turned into real losses, and so on. The studies used to support this argument are typically over long time periods (25 to 50 years) and end at a positive return for the portfolio. (The Seeking Alpha article referenced previously uses an estimated S&P 500 return since 1928.)

In my opinion, all of the statements above may be 100% true. But that still doesn’t mean time in the market is a prudent investment approach. Here’s why:

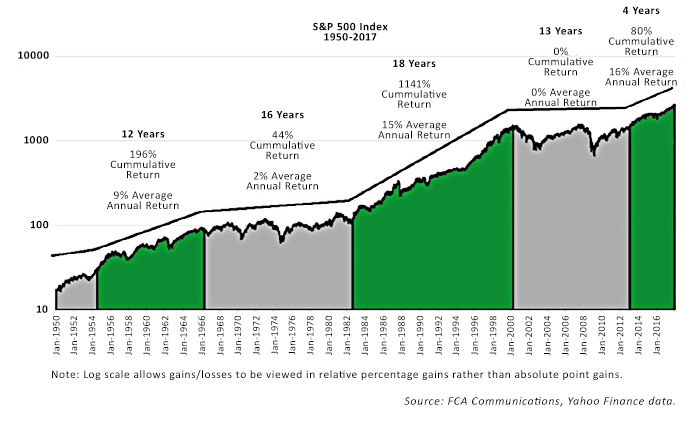

- Financial markets move in cycles. There is no evidence to show that their cyclical nature has changed. Time in the market does not diminish the possibility of encountering a bear market, it increases it. The longer one is invested, the more down markets one will encounter. (See Figure 1 below.)

- Not all investors have 25 to 50 years to invest and the fortitude to hold through devastating down markets until recovery.

- When the bear market happens matters. It does no good to be invested for 30 years and then see 50% of one’s portfolio vanish just at retirement or when one needs the funds.

- Past performance is not an indication of future returns. There is no guarantee that the market will recover as quickly or as dramatically as it has at times in the past. The S&P 500 decline in 2000–2002 took seven years to recover, and within months the market was falling again. It would be five more years—2013—before the S&P 500 again hit its 2000 high. The NASDAQ Composite did not recover fully for more than 15 years.

- Markets may recover, but individual stocks may not. Market history is littered with companies that did not survive the ravages of bear markets, technology shifts, and bad management.

- Data quoted in most “time in the market” defenses are averages. Averages are not reality. You can’t count on being able to walk across a river with an “average” depth of 3 feet.

- Simply preserving one’s initial investment isn’t enough. Investing only makes sense if there are gains exceeding the impact of taxes and inflation.

One of the strangest defenses of time in the market is that “it’s better to be in the market than on the sidelines.” That brings to mind a quote from economist John Kenneth Galbraith: “The sense of responsibility in the financial community for the community as a whole is not small. It is nearly nil.”

FIGURE 1: S&P 500 HISTORICAL TRENDS—THE MARKET MOVES IN CYCLES

Logarithmic scale: 1950–2017

Active investment management is a viable alternative to ‘time in the market’

The most common argument against active management is that no one has been able to consistently predict market tops and bottoms with great accuracy. True. But does it matter? What the investor really needs to know is “What is the trend?” and “How can I protect most of the gains my portfolio achieves?”

If an investment is increasing in value, one stays invested. If value is declining, it’s time to get out. Market volatility can make it difficult to determine an investment’s trend, but moving averages (MAs) have been used for decades to “smooth” price action and make trends easier to see. The simplicity of calculating a moving average allowed investors to use them considerably in advance of today’s computing powers.

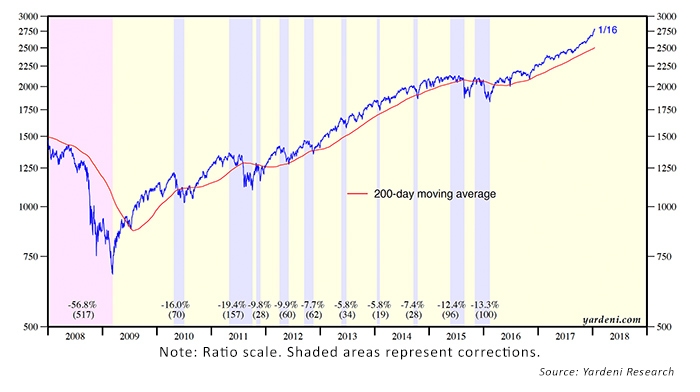

Among the most common indicators are the 200-day and 50-day moving averages. When the 200-day moving average is above the daily price, the odds are pretty good the investment is declining in value. The indicator is by no means perfect and can result in short-term whipsaws, but using it since 1975—when the first S&P 500 Index fund was introduced (the Vanguard Index Trust)—would have resulted in superior performance at considerably less risk. Figure 2 presents an example of this simple concept for the period 2008 to 2017.

FIGURE 2: S&P 500 BULL MARKETS, BEAR MARKETS, AND CORRECTIONS (2008–2017)

To reduce whipsaws, the 200-day moving average is often combined with a 50-day moving average, and then buy and sell signals are given at the crossing of the two moving averages. These signals identify that momentum is shifting in one direction and that a strong move is likely approaching. A buy signal is generated when the short-term average (50-day MA) crosses above the long-term average (200-day MA), while a sell signal is triggered by the short-term average crossing below the long-term average. (Figure 3)

FIGURE 3: S&P 500—200-DAY AND 50-DAY MOVING AVERAGES (1994–2017)

Today’s active managers have far more-sophisticated logarithms, models, and other esoteric tools at their disposal to determine market trend and optimal buy/sell times, but the 200- and 50-day moving averages—in their simplicity—demonstrate the potential for minimizing losses with “time out of the market.” Any time losses are reduced, the investor has more to invest at the market’s bottoms and potentially greater leverage for profitability.

Taking a fiduciary approach to the management of client assets demands the use of techniques and strategies that reduce the risk of declining markets to the client’s portfolio. Time in the market does not reduce risk or enhance returns. It merely assures that someone else will ultimately profit at the individual’s expense. Active management is a client-first approach to investing.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Proactive Advisor Magazine. These opinions are presented for educational purposes only.

Linda Ferentchak is the president of Financial Communications Associates. Ms. Ferentchak has worked in financial industry communications since 1979 and has an extensive background in investment and money-management philosophies and strategies. She is a member of the Business Marketing Association and holds the APR accreditation from the Public Relations Society of America. Her work has received numerous awards, including the American Marketing Association’s Gold Peak award. activemanagersresource.com

Linda Ferentchak is the president of Financial Communications Associates. Ms. Ferentchak has worked in financial industry communications since 1979 and has an extensive background in investment and money-management philosophies and strategies. She is a member of the Business Marketing Association and holds the APR accreditation from the Public Relations Society of America. Her work has received numerous awards, including the American Marketing Association’s Gold Peak award. activemanagersresource.com