The ultimate question for advisors: ‘Should I stay or should I go?’

The ultimate question for advisors: ‘Should I stay or should I go?’

Now, more than ever, advisors should formulate a succession plan—or at least explore the multiple options available for an economically sound and client-focused exit plan for the future.

The COVID-19 pandemic has spurred a wave of financial advisors calling it quits, or at least finally giving serious consideration as to how to go about properly transitioning their firms either to the next generation or to another firm.

And this is not just happening in the United States. Jeff Gans, founder and CEO of Purpose Advisor Solutions in Toronto, Canada, last year told The Globe and Mail that during the pandemic the number of advisors starting the succession-planning process with his firm tripled, and going into 2021 the number would likely rise fivefold.

“This is not going to slow down—it is only going to accelerate from here,” Gans said in October 2020.

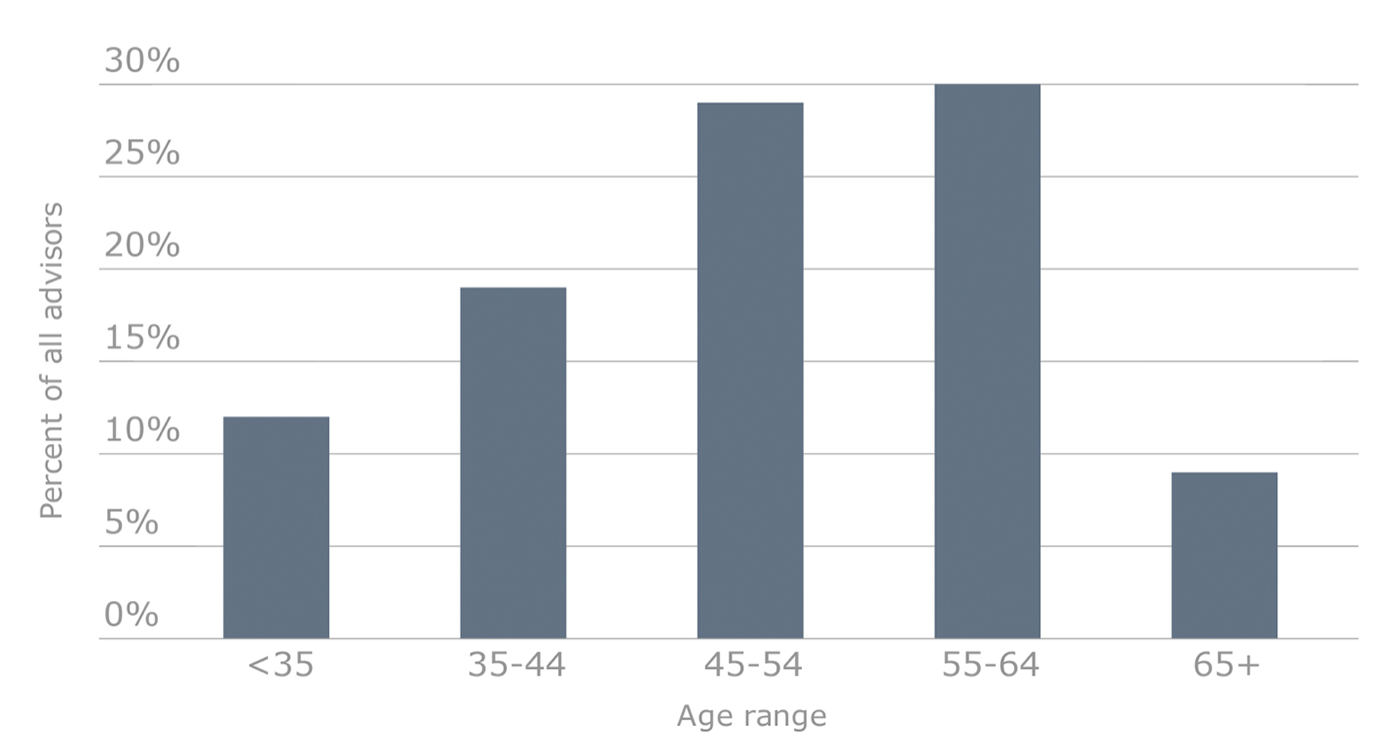

One thing is for certain: In the U.S., the wealth-management industry is ripe for a change of guard. The average age of advisors is about 55, and one in five are older than 65, according to a 2019 J.D. Power study.

A study by Cerulli and Associates shows a somewhat younger age skew among advisors but still finds that about 40% of financial advisors are over the age of 55.

Source: Cerulli Associates, Advisors Magazine

In large part based on the aging of the advisor population, Cerulli projects that 37% of today’s advisors are expected to retire over the next decade. This, says FA Magazine, will put “almost 39% of industry assets in motion.”

In this article, financial advisors and other industry participants explore why an increasing number of financial professionals are now either hanging up their hats or formulating a real plan on how to exit in the not too distant future—deciding whether to groom someone from their own firm to take over, sell to another firm, or just close their doors altogether.

The stakes are high—not just for advisory practice founders and their firms’ employees but also their clients and the families of those clients. As Ray Sclafani, founder of ClientWise, writes in his 2016 book, “You’ve Been Framed,” “financial advising is a noble profession” that is capable of not only impacting the current generation of clients that financial advisors work with but also “carries forward through multiple generations.”

Wendy Leung, senior consultant at Diamond Consultants LLC in Morristown, New Jersey, has seen advisors hasten their plans to retire—either right away or later, but this time with a concrete plan.

Wendy Leung, senior consultant at Diamond Consultants LLC in Morristown, New Jersey, has seen advisors hasten their plans to retire—either right away or later, but this time with a concrete plan.

“Some advisors, when forced by COVID to confront mortality—theirs, friends, and family—decided to expedite their retirement and enjoy life,” Leung says. “Since markets were high and many advisors had their best year ever from a revenue perspective, it was a great time to lock in a retirement payout from their firm. Or, if the advisor was independent, sell the business at a high-water mark and benefit from the lower capital gains tax rates that are still in effect.”

Conversely, some advisors who were thinking about retirement pushed off the decision when they realized they could work very effectively remotely, she says. Not having to come into an office, and the ability to work from wherever they want, is prompting some advisors who are nearing retirement to push out their timelines.

Julia Carlson, founder and CEO of Financial Freedom Wealth Management Group in Newport, Oregon, says the pandemic has caused older advisors “to look at what really matters.”

Julia Carlson, founder and CEO of Financial Freedom Wealth Management Group in Newport, Oregon, says the pandemic has caused older advisors “to look at what really matters.”

“Many have asked themselves whether they still want to run a business, manage the day-to-day details, and continue to work with clients,” Carlson says. “This was especially the case in the beginning when there was so much panic, including in the markets, and many advisors wanted out because they didn’t want to go through another recession or crisis again.”

At the very least, the pandemic has caused advisors to start thinking about succession planning, she says, noting that “the pandemic has shown us that our health is fragile, and it’s smart to put something in place.”

Often, independent advisors want a “homegrown” successor since it allows them to retain maximum control, Leung says. The first step is to evaluate the existing team to determine if there is someone at the firm that shows potential not only as an advisor but also as a leader and manager. “If so, then ensuring that this person is on the same page in terms of interest and timeline is important,” she says. “Equally important is being on the same page in terms of what the economics of the buyout will look like.”

Also, if the retiring advisor is looking for a front-loaded exit payment, does the acquiring advisor have access to the capital they will need for the buyout? If there is no one within the existing firm, then independents often will try to recruit a successor.

“The problem here is that it is a highly competitive market for young advisor talent, with the major firms offering large transition deals,” Leung says. “Since they often can’t compete, some independents will groom someone new to the business with the right education and connections—but this takes a long time and sometimes several candidates before finding the right fit.”

Mark Pitre, managing principal at California Financial Advisors in San Ramon, California, says that after decades of working together, he and his three partners began working on a succession plan in 2015.

Mark Pitre, managing principal at California Financial Advisors in San Ramon, California, says that after decades of working together, he and his three partners began working on a succession plan in 2015.

“Like most advisors, during the first decade, we focused on being the best practitioners, building our practice and our firm,” Pitre says. “The concept of succession planning was actually something you hope you have to deal with in the future, because it means you have been successful and have something worth passing on.”

The partners knew they had to do something about succession planning, but they kept putting it off, he says. Then one of the partners unexpectedly became very ill and, as a result, the other partners and Pitre had to take on his client relationships and firm responsibilities for about a year.

“Pursuant to that, we realized that we really needed to have a deep bench of advisors, and along with that, the concept of succession planning became much more prevalent after we saw firsthand what can happen without those processes in place,” he says.

In order to build “that deep bench of next-generation advisors,” the partners decided that they needed to develop an intern program and have them work with the firm over the summer months and winter breaks, Pitre says. From that, the partners hired three interns full-time, and “now they are integral to our succession planning.”

“Over time, we have outlined to them that they are the firm’s next generation of principals, and as a result, we listen to their input in regards to helping us make decisions about the direction of the firm,” he says.

As the pandemic caused a rapid acceptance of remote technology, the partners found that the firm’s younger advisors all had a much better skill set in embracing the available technology.

“That allowed us to be much more efficient and effective than we would have been without them,” Pitre says. “It allowed them to accelerate their development of relationships with our existing clients and, at the same time, be instrumental in initiating the onset of new client relationships.”

Succession planning has evolved. Advisors are not only engaging second-generation advisors, but they are also creating equity for them so they can one day possibly buy the practice, says Brad Bueermann, CEO of FP Transitions in Lake Oswego, Oregon.

Succession planning has evolved. Advisors are not only engaging second-generation advisors, but they are also creating equity for them so they can one day possibly buy the practice, says Brad Bueermann, CEO of FP Transitions in Lake Oswego, Oregon.

“This can create a more sustainable firm—building a practice that will endure for a far longer time than the career horizon of the founder,” Bueermann says. “It’s important to engage everyone in the firm to serve clients as a team. Building equity pathways is a great way to do that.”

It’s smart to service as a team because the needs of clients regarding their future financial goals generally exceed the career horizon of their advisors, sometimes by many years, he says. When clients are ready to retire, in many cases, their advisor is also ready to retire, so it can be disruptive when another advisor who might not have been involved with those clients takes over.

“Often, single owners think of clients as belonging to them and not in terms of belonging to the firm,” Bueermann says. “Therefore, clients don’t get serviced by a team. But when junior advisors have equity pathways, the opportunity to build service teams increases and the transition when the founder retires is more seamless as others take over those client accounts.”

Over the past year, FP Transitions has been fielding more calls from advisors to help structure equity pathways for their team.

“As the pandemic has accelerated the trend of junior advisors leaving for greener pastures, advisors realize they may need to create opportunities to give them equity so they are better able to retain key people and their managed clients and assets,” he says. “This topic has been so popular that a recent webinar on the topic had 900 advisors attending.”

Not all advisors in the firm need to be offered equity—just those who are being groomed to be leaders of the business, Bueermann says. As for choosing one advisor to be head of the firm after the founder retires, the founder has “plenty of time” to decide that once equity pathways have been created.

Selling the firm or merging into a larger firm can be an excellent way to solve for succession, Leung says. The right buyer will have a next-gen bench of talent that is already established and a broader infrastructure to support servicing clients. The outside entity will also have enough capital and experience in acquiring other practices to make a deal happen.

“If you are considering selling or merging to solve for succession, do it while the business continues to be in growth mode,” she says. “Don’t wait until clients are spending down assets and aging along with you.”

Advisors should get educated now on what drives valuations or hire someone who is an expert to help them Leung says. Above all, advisors need to make sure that their expectations are reasonable and that they are neither undervaluing nor overinflating the value of their business.

Structuring equity pathways for junior advisors isn’t appropriate for all firms, Bueermann says. Some firms are still too small, so in those cases, it might be better to merge with a firm that is larger, or even the same size, to gain this capability.

On the other hand, even firms that offer equity to other partners may, in the end, opt to sell to an outside party. Carlson thinks ultimately that may be her route as well.

Carlson started the succession-planning process with FP Transitions in the summer of 2019, turning to them because her business had become pretty large—almost $350 million in assets—and she needed to protect it. The firm was also considering acquisitions, and Carlson wanted to be prepared when the right fit presented itself.

“I also desired to figure out what the firm should look like beyond me,” she says. “While I’m not planning to retire any time soon—I’m 44—I wanted to protect my clients and my family, ensuring that if anything were to happen to me, everything would be seamless.”

Last summer, Carlson’s firm changed ownership and its structure. She expanded management by two additional partners, who had each been with her for about seven years, giving them equity in the business.

“While I’m the founder of the company and it’s been my baby, these two have been key players who helped me build the business, so I wanted to reward them,” she says. “I also wanted them to be part of the business because they are critical to our success.”

One partner is “a very experienced executive” who helps manage and operate the business, Carlson says. The partner is 72, so giving him equity in the business allows him to eventually sell his stock as part of his retirement plan.

“He has also been impactful to have in the business as we have hired more employees. My strength has not been in management—I’m more entrepreneurial and strong in marketing and advising,” she says. “His skills at managing employees, developing our company culture, and grooming the next generation of leaders has freed me up to do my best work—managing the firm’s investments, helping clients, attracting new clients, implementing marketing strategy, doing speaking gigs, and writing a book.”

Carlson’s succession plan allows for flexibility on how she will exit the business, depending on the situation at the time when she’s nearing retirement. She believes it could be difficult for any advisor within the firm to purchase the firm, even if they have some equity, because it’s currently valued at $7 million and growing rapidly, and they may not be able to buy such a large asset.

“I also have three kids, so I never want to rule out including them in a succession plan if they show interest,” Carlson says. “In the long run, it would most likely make sense to sell to a bigger third party—but a lot can happen in the next 20 years.”

While Carlson’s succession plan is flexible, the documents are now in place that outline the process for what happens if either she or her partners decide to exit or retire, or if they have serious health issues.

“This provides great peace of mind for all parties involved,” she says. “I also have FP Transitions as a resource, and they have been a great partner.”

Advisors shouldn’t wait until they are ready to retire to start thinking about succession, Leung says. A well-thought-out succession plan can improve business valuation—“it weatherproofs the business.” It can also result in greater growth since clients and next-gen inheritors are more likely to work with a firm that has a clear, client-responsive plan and team for the future.

Pitre is familiar with many advisory firms that have partner demographics similar to California Financial Advisors, and the concept of succession planning has come up in discussions. They know they need to do something about succession planning and bring in new advisors, but they are hesitant about the required time and monetary investment associated with that direction.

“But all I’ve seen with the interjection of new advisors is that there is an energy to them, and a synergy that develops. As older clients pass their assets to their adult children, our young advisors can often relate to these younger clients much more effectively than older advisors,” he says.

“So don’t be so concerned about the initial investment in money and time—because the benefits young advisors bring are so much better than what you may think,” Pitre says.

***

The COVID-19 pandemic has had a profound impact on how financial advisors are thinking about succession planning or exiting their firm. For many advisors, it has accelerated their timeline. For others, the adoption of more remote practices and greater use of technology has led them to consider staying in the business longer than they anticipated.

Even if deciding to remain at the firm for the foreseeable future, advisors should formulate a succession plan now, building in some options for later consideration—grooming from within, bringing in a would-be successor from the outside, selling to another entity, or shuttering the firm altogether.

No matter how advisors are thinking about their future career plans, one thing is certain: The pandemic of 2020–2021 has prompted a period of self-examination and a heightened exploration of what is most important in our personal, family, and business lives.