Inflation perceptions and the ‘money illusion’

Inflation perceptions and the ‘money illusion’

Inflation is as much of a perceptual issue as an economic one. It’s just as important for advisors to understand how clients view inflation as it is to effectively manage its impact on their portfolios.

Inflation remains one of the leading topics discussed in both the financial and general news media. The all-important consumer price index (CPI) rose 0.5% in December, after a 0.8% increase for November. This leaves us with a 12-month increase of 7.0%, a level not seen since 1982.

While economists and policymakers rancorously debate what’s causing it, how temporary it might be, and what the implications are for Federal Reserve policy, the effect on investor behavior is likely to be much more predictable. For many, it has put inflation back on their radar screens for the first time in decades. And that means advisors need to be prepared.

In a perfectly rational world, every investment would be assessed for its risk-adjusted, after-tax, after-inflation return. In rare corners of institutional investing, that is actually the case. But among the investing population at large, that’s not even close to how people think. Constrained more by pervasive psychological biases and discomforts, most investors tend to underestimate risks and largely ignore taxes and inflation on their individual investments. They prefer to bask in the innocent glow of overstated nominal returns, knowing full well that they are not real but feeling much better about it anyway.

That’s not to say that people deny the existence of risk, tax, and inflation. They will openly acknowledge all three. It’s just that instead of dealing with them as they affect individual investments, people prefer to deal with them as an adjustment to their holdings at the portfolio level. Thus, when tax rates go up, the knee-jerk reaction is to consider adding more municipal bonds or real estate. When risks are perceived as higher, people move into more defensive or dividend-paying stocks. And when inflation rises, they start looking more seriously at adding gold, commodities, and TIPS (Treasury Inflation-Protected Securities).

Don’t scoff, advisors—most of you are just as guilty of this! Chalk it up to being human.

Like other perceptual anomalies that plague us, this is not confined solely to investing. The way we manage our diets has the same behavioral characteristics. Instead of measuring each individual food we eat for its healthy characteristics, many of us believe that adding a few healthy things to our diets means we are eating healthier overall.

The fallacy of this logic was explicitly illustrated by research conducted for a prominent fast-food chain. At a neutral location, people were shown a sample of the chain’s fare and asked to rate whether they would classify the meal shown as a generally healthy one. Most gave poor ratings. Researchers then took the exact same plate of food, added a single celery stick, and then put the same question to a new sample of people. The majority now rated it as healthy.

Unfortunately, there is no difference between the people in this study and the ones who believe that if inflation rises, they can just add a little gold to their holdings and that will ensure they have a positive real return from their entire portfolio.

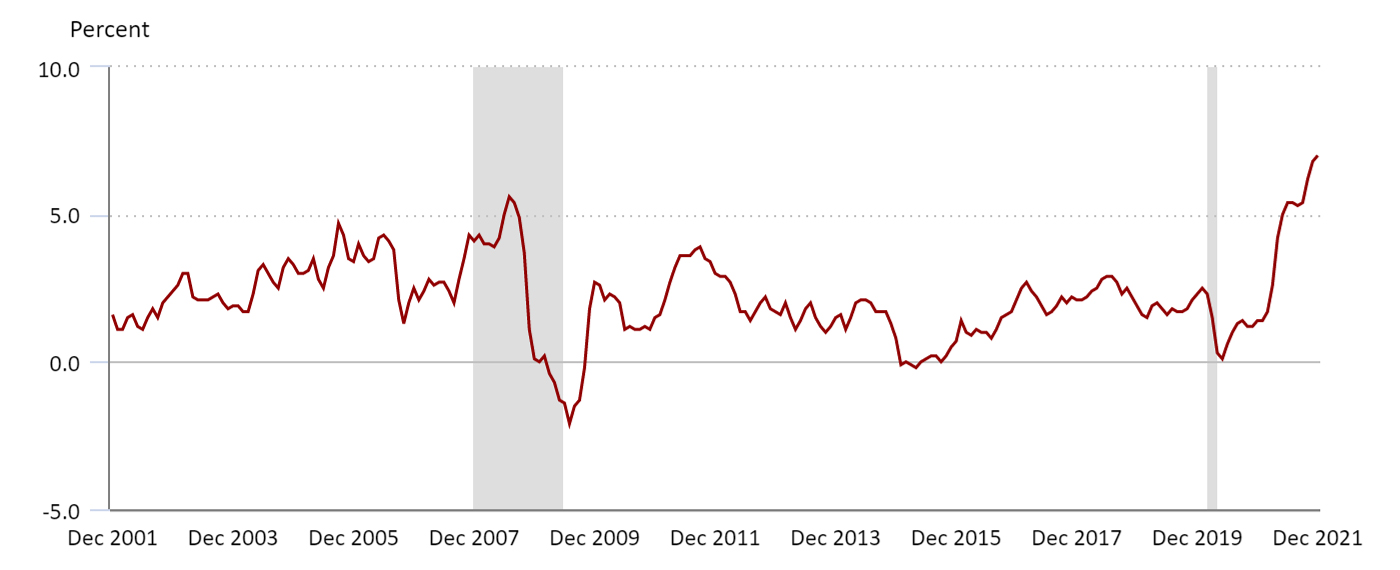

Inflation is a known demon to investment managers and advisors, wrestled with many times historically and widely addressed in financial circles. But for the better part of four decades in the U.S., the 12-month CPI has meandered between 0%–5%, causing relatively little concern to investors, who were happy enough to do what comes naturally to them—ignore it. Given its lengthy repose in the low single digits, inflation is actually something the younger generations of investors have never really faced at all.

Source: U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics

Nonetheless, how investors perceive inflation is so well known, it even has its own name: the “money illusion.”

The term was first used by economist Irving Fisher in the 1920s and has stood the test of time through the era of John Maynard Keynes and more recently with Robert Shiller. It has been the subject of multiple books, and the premise was identified long before we had the behavioral insights to help explain it.

The money illusion is pervasive, though actually rather simple. It essentially says that people ignore the effects of inflation on their income and wealth, viewing both in nominal terms rather than real terms. In other words, people are content to overstate increases in wealth or income, even while knowing intellectually that their buying power erodes steadily over time.

Yet people do understand the concept of inflation and are all too well aware of its existence. We simply focus on it from the consumer perspective rather than the investor perspective, with people broadly lamenting the relentless increases in price they experience over time.

Taxes work the same way. Few people could tell you what their marginal tax rate is or their after-tax returns on anything but tax-free instruments themselves. But most are quite concerned about minimizing taxes wherever they can. The focus is not on the overall amount of tax we pay or the actual rate, since both of those figures represent uncomfortable numbers to face. Instead, we think in terms of simply saving on taxes where there is a choice in the matter, like owning real estate over bonds, maximizing contributions to retirement plans, or making investment decisions that will minimize capital gains taxes.

But would people actually want to have their after-tax returns prominently displayed at the bottom of their statements?

Why people exhibit this anomalous behavior is deeply rooted in our subconscious and shares the same roots with other mental foibles such as overconfidence, loss aversion, and mental accounting. The plain truth is that we understand things such as taxes and inflation, but they are downright uncomfortable facts to face. The industry doesn’t help us either. What firm is going to be eager to convey the truth about real “after inflation” returns to investors?

Even in financial-planning analysis, where advisors more or less have to consider inflation, it is primarily examined in the context of future retirement expenses, rather than expressed in the context of investment returns. Thus, downplaying inflation-adjusted returns (which psychologically helps us all feel better about our accumulated wealth) seems to be the way both advisors and their clients generally deal with something that is largely out of their control.

And while diligent advisors may incorporate inflation assumptions in every plan, are those plans updated when we see spikes the way we have in 2021? Are new forward-looking assumptions analyzed and incorporated for all clients?

As inflation concerns make their way to the surface again, the money illusion is unlikely to abate anytime soon. For one thing, the worse inflation gets, the less likely anyone will want to know what they’re getting for real returns. What if, heaven forbid, the numbers are negative? In addition, inflation is a moving target, making it difficult for people to continually update in their heads. And CPI may or may not apply to one’s individual spending habits, so it is only an approximation anyway.

Yes, the money illusion is misguided, but that doesn’t stop us from exhibiting it. One of the most recent books on the subject comes from Scott Sumner and is titled “The Money Illusion: Market Monetarism, the Great Recession, and the Future of Monetary Policy.” In it, the author illustrates the absurdity of the money illusion with a simple example.

A person points out that their son was 1 yard in height at around 4 years of age and that 30 years later, he is now 6 feet tall. This, they proclaim, makes him now six times as tall. Most people would find such a statement totally absurd since the unit of measurement changed from yards to feet—units that differ in value by a factor of three.

On the other hand, if a person tells us that their income right out of college was $20,000 annually and that over 30 years it has grown to $120,000 annually, they could boast that their income is up sixfold. None of us would question that at all since it deals with dollars in both cases.

Sumner’s point is that if the CPI tripled over those 30 years, say from 1.0 to 3.0, the current dollar would indeed be different from the former dollar by the same factor of three, rendering the two situations equally absurd.

Our focus on nominal investment returns doesn’t mean that we aren’t concerned about inflation. We just establish mental benchmarks that serve as thresholds for our concerns, just as a fever of, say, 100 degrees doesn’t pass the threshold for seeing a doctor, but 103 certainly would.

For many people, it’s a safe bet that crossing the 5% level raised some degree of inflation concern, especially when the prognosis calls for more of the same for at least the next year as well. That concern is no doubt heightened further by the media alarmists who proclaim that the recent spike is not as temporary as the Fed would like us to believe. People will deal with this concern more or less in the same way they deal with a high fever—they’ll go looking for an “inflationitis” pill that can be prescribed for their portfolios to make them healthy again.

That’s where the advisor’s challenge begins. Do you placate the client with a token investment in assets perceived to offer an inflation hedge, or do you reexamine the entire portfolio from the perspective of real return, laying bare the true after-inflation returns that the client is getting with current assets? Clearly, you can’t just say “Take two gold ETFs and call me in the morning.”

The good news is that advisors do have a number of anti-inflation pills in their medicine kits, even if they haven’t used them much since Michael Jackson released the “Thriller” album. The typical anti-inflation add-ons are well publicized: real estate, gold, commodities, TIPs, and stocks in companies that have some degree of price inelasticity. (If you have forgotten these traditional inflation investment “solutions,” the financial media is only too happy in today’s environment to provide reminders.)

These are not givens, however, nor are they appropriate for all clients. In addition, not all periods of high inflation are the same, and some of the standard inflation fighters haven’t necessarily lived up to their reputation in all situations. And how will these “solutions” fare in today’s interest-rate environment?

On top of that, advisors will likely hear something today from their clients that was never before uttered in an inflation conversation: “Should I purchase bitcoin as an inflation hedge?” The point is that advisors may need to revisit that former inflation playbook and get a fresh view of its merits in today’s environment.

More to the point, that’s not the only challenge advisors need to face. Once they come up with an inflation plan for portfolios, the more difficult challenge will be to create an inflation strategy for clients.

Here are some questions to ask yourself as you revisit your inflation playbook and open conversations with your clients about the various options:

- How critical of an issue do you as the advisor feel inflation is right now, and what asset classes do you believe will be most affected?

- What are the best ways to counter inflation, considering the uniqueness of today’s economic, interest-rate, and market scenarios relative to historical periods of high inflation?

- Will the inflation strategy have a timeline? A timeline for the inflation strategy could be very helpful in managing client expectations. Ideally, that should include target levels of inflation that would lead to further changes to the financial or investment plan.

- How will you measure the effectiveness of any inflation-oriented changes in the client’s assets if the client doesn’t typically view their returns on an after-inflation basis?

- Will you proactively connect with all clients regarding inflation or just placate the ones who raise the issue?

- Should all financial plans be redone with new inflation projections? And how far into the future should those projections go at current levels? As a recent blog post points out, will “even ‘just’ higher near-term inflation negatively impact recently retired clients, who are particularly susceptible to sequence of return risk?”

- What will you say to clients who ask whether cryptocurrency represents an inflation hedge?

Advisors are facing external circumstances in the case of inflation that will no doubt cause concern among many of their clients (especially those who vividly recall the 1970s). To serve their clients most effectively, they will have to decide whether they want to serve them a new, truly healthy meal—or place a celery stick on the one they already have.

New this week:

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.

Richard Lehman is the founder/CEO of Alt Investing 2.0 and an adjunct finance professor at both UC Berkeley Extension and UCLA Extension. He specializes in behavioral finance and alternative investments, and has authored three books. He has more than 30 years of experience in financial services, working for major Wall Street firms, banks, and financial-data companies.