Are index funds the next market ‘bubble’?

Are index funds the next market ‘bubble’?

While bear markets are inevitable, will their impact be exacerbated by the growth of passive index funds—and the accompanying “madness of crowds”?

Along much the same line, when a particular investment approach becomes mainstream and the media favorite, you pretty much know that, before the story is over, it’s going down and taking a lot of investors with it. If nominations are being taken for the next medallion-winning, pain-inducing investment approach, passive index investing may well be a front-runner.

Classic bubbles throughout history

Leading to the pessimistic outlook for investment fads is the reality that over the history of investing, there has yet to be a popular investment approach with a happy ending. An interesting read on the bubble mentality of markets is Charles Mackay’s 1841 classic “Extraordinary Popular Delusions and the Madness of Crowds.”

MacKay’s detailed explanations of the South Sea bubble, the Mississippi scheme, and “Tulipmania,” along with the widespread pursuit of other delusions by people and nations over the years, are remarkably contemporary. John Law, the originator of the Mississippi scheme, would have been completely at home creating collateralized mortgage obligations.

The South Sea bubble originated in 1711 when the South Sea Company was founded to restore the public credit of England. A company of merchants undertook the public debt for the promise of 6% interest, later reducing the interest for the right to a monopoly of trade to the South Seas, where the public believed immense riches awaited. Although unsuccessful in trading in the region, the company nevertheless persuaded the British government to convert more of its debt into stock. In January 1720, fueled by rumors, speculation in the stock took off. The stratospheric valuation of the South Sea Company spawned “bubble companies” promising riches from elaborate schemes, and the rush for wealth was on. By September, reality (and its consequences) set in, and despite the efforts of government and banks, the bubble burst.

The Mississippi scheme was created by John Law, a Scotsman and son of a banker with a love for numbers and gambling. Law gained his reputation as a financier by persuading the French regent to convert the country to paper currency to restore the fortunes of France (one of the earliest lessons on why providing the government with printing presses can have a very bad ending). His bank, Law & Company, became the means of exchanging notes for coin. Law also proposed to the regent that he grant the company the exclusive privilege of trading to the great river Mississippi and the province of Louisiana—thought to abound in precious metals. An initial 200,000 shares were issued in 1717, and a frenzy of speculation began to seize the country. The collapse of the South Sea Company exposed the financial manipulations of Law & Company, and by 1721, Law was running for his life.

Tulips first made their way to Holland from Constantinople and were the rage of the wealthy and those aspiring to be wealthy in the early 1600s. In 1634, the popularity of the tulip among the Dutch became an obsession, and a single bulb of one of the rarer varieties commanded a small fortune. By 1636, tulip bulbs (and a form of futures contracts) were sold on exchanges in numerous Dutch towns and cities. The mania peaked in November of that year, and a bulb on which one might bet one’s financial future became virtually worthless.

While these early examples might seem a bit extreme, bubbles have persisted over time, including these more recent manias:

The cycle of investor sentiment

At the center of every market bubble is a common factor: the remarkably predictable investor—typically aided and abetted by the current government’s policies (or lack thereof in terms of weak oversight). In the worst case, the implosion of the bubble can result in civic unrest, but more typically it ends up costing investors and government funds, which have often been invested in the same vehicles. In every market boom and bust, the same cycle of investor sentiment has occurred.

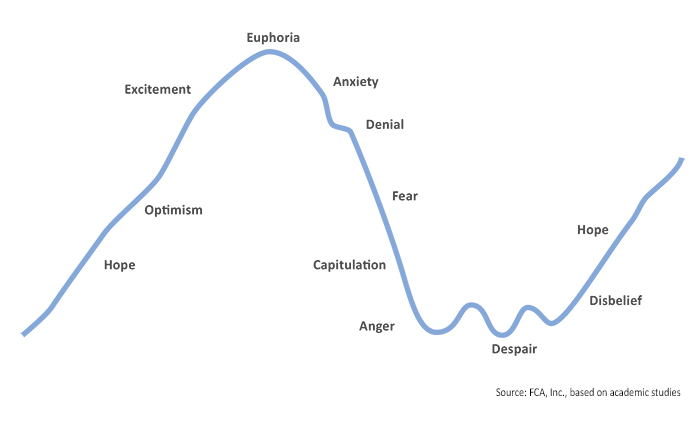

FIGURE 1: THE INVESTOR SENTIMENT CYCLE

The cycle begins with hope—hope that financial security is possible, that one has found an investment that will work and create wealth. The investor is still cautious, remembering the lessons of time. However, as positive results accumulate, optimism builds, and the thought that “this time it is different” begins to gain credibility. By the time the investment peaks, investors are euphoric, convinced of their brilliance in making the investment decision.

Unfortunately, along the way, more and more people have taken up the same investment or approach, attracted by the gains and promotion of the investment. Popularity is inevitably the curse of successful investing. As demand drives the price of the investment beyond reasonable valuations, speculation takes over. Rather than investing based on the value of a company or sector and its ability to produce profits, the investor chases the “hot hand.” Demand creates value. As the supply of new money falls, however, the upward pressure on prices begins to falter and smart money starts looking for the exit.

As anxiety sets in, the investor is typically reassured by media and financial experts that this is the only practical way to invest. Denial and the belief that prices will recover is common. Finally, the pain is too great and fear takes over. At this point, the investor capitulates and liquidates the position—often at considerable loss—and retires to the sidelines angry at the fates, the markets, and the “them” that caused the loss. When a new investment opportunity or trend begins to attract attention, the common reaction is disbelief, until hope once again begins to lure investors back into the market.

Will the growth of passive index investing intensify the next market crash?

How does this apply to passive index investing? In the growing popularity of passive index investing, many of the same patterns of investor sentiment are taking shape. Individual investors are well into the optimistic phase—evidenced by the flow of assets into index funds—while the media waxes euphoric about the benefits of passive investing and the foolishness of paying fees when passive investing can, in many recent years, outperform managed strategies.

According to a recent report from Broadridge Financial Solutions Inc., “The usage of passive investment products, ETFs and index funds, hit all-time highs in 2016.” More than $610 billion—or 85%—of the new asset that flowed through “third-party channels” such as brokers, registered investment advisors, and banks went into index funds or passive ETFs.

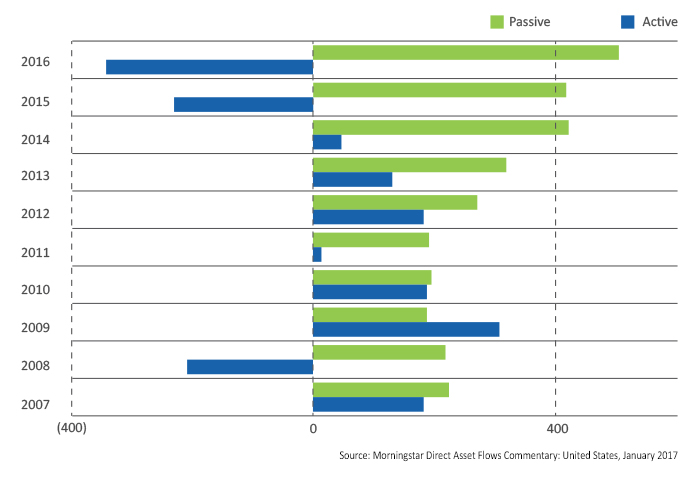

FIGURE 2: U.S. MARKET ACTIVE VS. PASSIVE FLOWS (2007–2016)

Passive index investing is the financial media’s current favorite obsession when it comes to investment strategies. Even the federal government’s attempt to set fiduciary standards that are “in the investor’s best interest” has tended to favor passive index investing, with its relatively lower fees. Index Fund Advisors proclaims, “This is music to our ears, as many investors and professionals are starting to come to realize that adopting a lower-cost, passive approach to their personal investing is a more prudent strategy than the active approach that has dominated the industry for decades.”

CNBC noted in April 2017, “In the past decade, there’s been a seismic shift from active to passive management, i.e., from mutual funds run by ersatz Peter Lynches to index funds and ETFs that track the market. … That [2016] was the greatest calendar-year asset change in the last decade, during which more than $1 trillion has shifted from active to passive U.S. equity funds.”

Strong market performance enhances demand for passive products, exacerbating the uptrend and creating protracted periods of low volatility. The shift toward passive index investing concentrates investments in a few large products where demand/momentum drives prices rather than the ability of the companies within the index to create value. As passive investing grows, it crowds out active managers who normally play a key role in market efficiency. The emphasis on market cap in many indexes also creates a misallocation of capital away from smaller companies.

This concentration increases market risk. Markets become more susceptible to the flow of new money into a few large passive products. When markets inevitably reverse, corrections may become deeper. With an index fund, the investor may have no realistic means of valuing the portfolio, weakening confidence in the ability of the index to recover from corrections. As a result, many market analysts believe upcoming crashes will be “bigger and badder.”

There is also the potential for current trading technologies to compress the market’s decline, making the rush for the door more difficult to execute and driving prices down faster.

While most active investment strategies ride the upward momentum of the market with the objective of moving to safety when the market trend reverses, the window of opportunity may be very narrow in an index-driven world. Active risk management for client portfolios becomes more critical than ever. As index investing intensifies, so should all investors’ sense of concern.

The opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily represent the views of Proactive Advisor Magazine. These opinions are presented for educational purposes only.

Linda Ferentchak is the president of Financial Communications Associates. Ms. Ferentchak has worked in financial industry communications since 1979 and has an extensive background in investment and money-management philosophies and strategies. She is a member of the Business Marketing Association and holds the APR accreditation from the Public Relations Society of America. Her work has received numerous awards, including the American Marketing Association’s Gold Peak award. activemanagersresource.com

Linda Ferentchak is the president of Financial Communications Associates. Ms. Ferentchak has worked in financial industry communications since 1979 and has an extensive background in investment and money-management philosophies and strategies. She is a member of the Business Marketing Association and holds the APR accreditation from the Public Relations Society of America. Her work has received numerous awards, including the American Marketing Association’s Gold Peak award. activemanagersresource.com