Black swans & the ‘10 best days’ myth: Can investors prepare for market outliers?

Black swans & the ‘10 best days’ myth: Can investors prepare for market outliers?

How much effect do market outliers have on long-term performance? Can the investor prepare for these anomalies, or are they truly ‘black swans’ that cannot be managed?

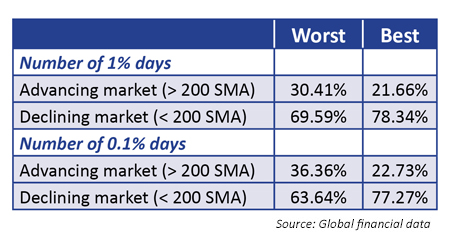

Mr. Faber’s analysis addresses several assumptions behind the “missing the 10-best-days” argument, which, as he says, is “often proffered by advocates of buy-and-hold investing.” He also examines the issues of how market “outliers tend to cluster and the majority of both good and bad outliers occur once markets have already been declining.” Mr. Faber advocates “that investors attempt to avoid declining markets where most of the volatility lies” and concludes that “market timing and risk management is indeed possible, and beneficial, to the investor.”

Taleb defines a black swan as an outlier outside the realm of regular expectations because nothing in the past can convincingly point to its occurrence. The event carries an extreme impact and is often “explained” after the fact, giving the impression that it is explainable and could have been predicted.

Many market commentators have latched on to this term to describe all financial market events. However, the existence of large outlier events known as “fat-tailed distributions” in financial market returns has been well-documented for more than 40 years (see Benoit Mandelbrot’s “The Variation of Certain Speculative Prices” and Eugene Fama’s “The Behavior of Stock-Market Prices”). While the financial media have only recently revisited the fat-tail concept (due largely to the occurrence of the Internet bust in 2000–2003, as well as the global financial meltdown in 2008 and 2009), it has been a thoroughly studied field in finance over the past several decades.

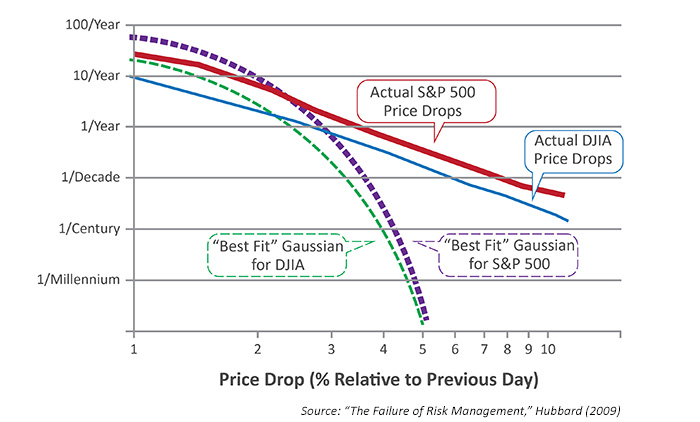

Financial market return distributions are similar to fractal systems that follow a power-law distribution (which is useful in describing events such as earthquakes and volcanic eruptions). Below is a chart from the book “The Failure of Risk Management” by Douglas Hubbard, which illustrates the inability of the Gaussian models to account for large outlier moves in financial markets. In a normal-distribution world, a 5% decline in the Dow in a single trading day should not have happened in the past 100 years. In reality, it has happened nearly 100 times.

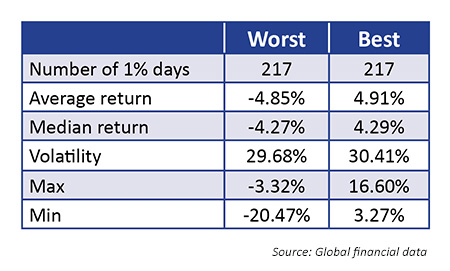

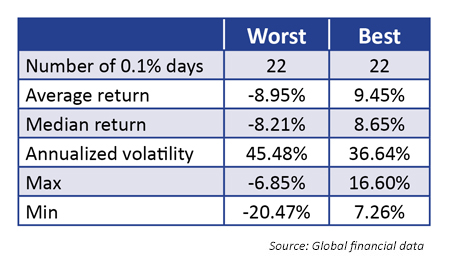

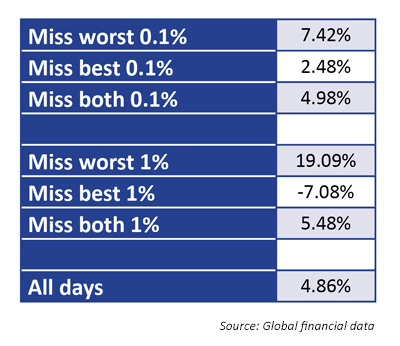

One of the most common rhetorical bulwarks in the defense of buy-and-hold investing is to demonstrate the effects of missing the best 10 days in the market and how that would affect the compounded return to investors. This is perhaps one of the most misleading statistics in our profession (another being the Brinson asset-allocation study misquote). A number of academic papers have examined the effects of missing both the 10 best and the 10 worst days (two good ones are Paul Gire’s “Missing the Ten Best,” published in the Journal of Financial Planning, and Richard Ahrens’ “Missing the 10 Best Days”).

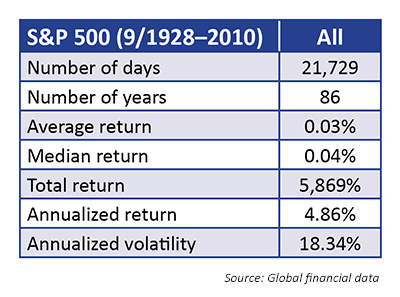

In Table 1, we examine the S&P 500 (and the broad market predecessor) from 1928 to 2010. We use price history only, as dividends will not have a meaningful impact on the daily return data.

ANNUALIZED RETURNS (9/1928–2010), PRICE ONLY

What are they missing?

When you are making money, you are thinking about the new car you are going to buy, how smart you are (and how much smarter you are than your neighbor), the vacation you are going to take, and the (second, third, fourth) house you are going to buy. The part of the brain that is firing nonstop here is the same region that gets stimulated by cocaine or morphine.

However, when you are losing money, you are probably not opening your account statements. Instead, you are thinking about how dumb you are (and how stupid you were to listen to your neighbor) and how you are going to pay for that second house. Even thinking about investing is likely to elicit feelings of revulsion. The brain processes portfolio losses in the same region that is stimulated by the flight response. (For more in-depth discussions on behavioral biases, please consult some of the work of the great MIT professor, Andrew Lo.)

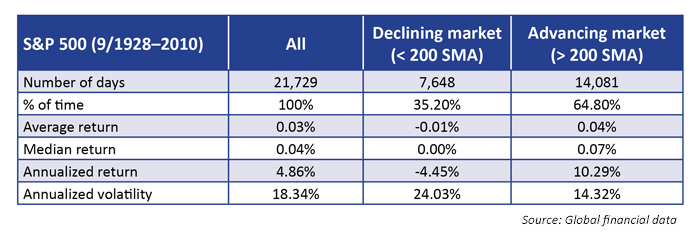

Table 5 examines the returns (and, more importantly, the volatility) when the market is appreciating versus declining (defined as above or below the 200-day simple moving average, or SMA). Based on this data, and that of Table 6, it is little wonder that the volatility found in declining markets can have such a profound impact on investors’ emotional responses.

“What matters is the particular, not the average. Some of the most successful investors are those who did, in fact, get the timing right.”

Astute market analysts must also realize the drawbacks and downsides of any indicator or investment approach. In the case of a trend-following approach, there are two main drawbacks. First, in trendless markets, whipsaws can occur that have negative effects on the portfolio. Second, and perhaps more important, a trend-following approach does not guarantee the investor will miss a black swan event in an uptrend. A very sharp move against the trend will not allow the investor or model time to react and protect against such a move. Investors looking for protection against this sort of event can use derivatives such as options to protect the portfolio when fully invested (so-called tail-risk insurance), or consequently, to gain long exposure when mostly in cash and bonds (risk of missing out). This process could be a net cost (insurance) to the portfolio.

That is the point of risk management: understanding and trying to account for as many risks as you can.

Our broad summary points from this analysis?

- The stock market historically has gone up about two-thirds of the time.

- All of the stock market return occurs when the market is already uptrending.

- The volatility is much higher when the market is declining.

- Most of the best and worst days occur when the market is already declining. Reason: see #3. Markets are much riskier than models that assume normal distributions can be used to predict.

- The reason markets are more volatile when declining is because investors use a different part of their brain when making money than when losing money.

Meb Faber is a co-founder and the chief investment officer of Cambria Investment Management. Mr. Faber is the manager of Cambria’s ETFs, separate accounts and private investment funds. Mr. Faber has authored numerous white papers and three books: "Shareholder Yield," "The Ivy Portfolio," and "Global Value." He is a frequent speaker and writer on investment strategies and has been featured in Barron’s, The New York Times, and The New Yorker. Mr. Faber graduated from the University of Virginia with a double major in engineering science and biology. cambriafunds.com, mebfaber.com

Meb Faber is a co-founder and the chief investment officer of Cambria Investment Management. Mr. Faber is the manager of Cambria’s ETFs, separate accounts and private investment funds. Mr. Faber has authored numerous white papers and three books: "Shareholder Yield," "The Ivy Portfolio," and "Global Value." He is a frequent speaker and writer on investment strategies and has been featured in Barron’s, The New York Times, and The New Yorker. Mr. Faber graduated from the University of Virginia with a double major in engineering science and biology. cambriafunds.com, mebfaber.com